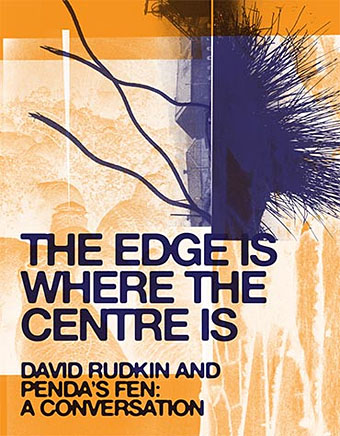

Design by Rob Carmichael.

“I am afflicted by images, by things that are seen, pictures of things. They are extraordinary, momentary, but they stay with me.” (David Rudkin, 1964)

“The pattern under the plough, the occult history of Albion – the British Dreamtime – lies waiting to be discovered by anyone with the right mental equipment.” (Rob Young, Electric Eden)

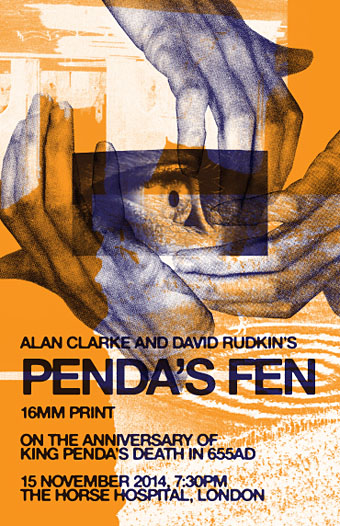

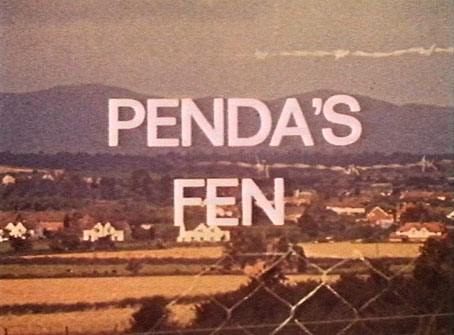

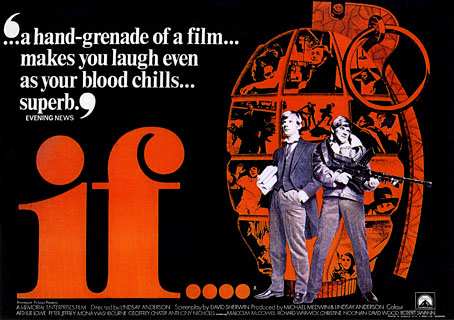

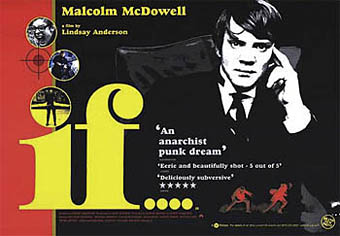

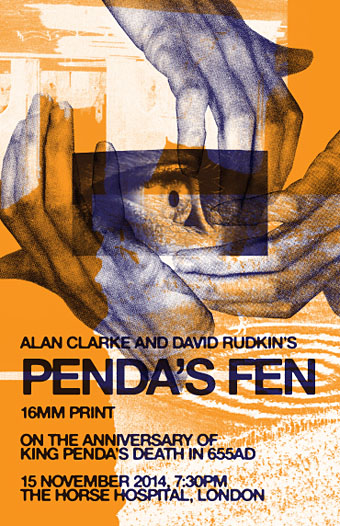

Penda’s Fen, written by David Rudkin and directed by Alan Clarke, is one of the key films in the pantheon of what has been called The Old Weird Albion. A radical archaeology of Deep England, a work of dark pastoral, a praise-song to anarchistic transformation, as militant a rejection of imperial identity as Lindsay Anderson’s If…, it culminates with perhaps the most euphoric revelation in British cinema: “My race is mixed. My sex is mixed. I am woman and man, light with darkness, nothing pure!”

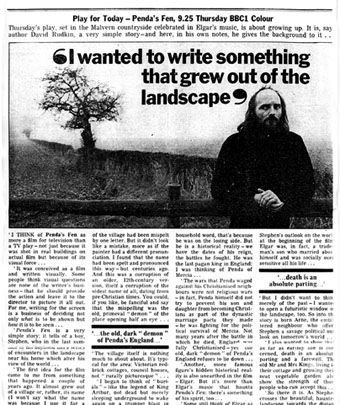

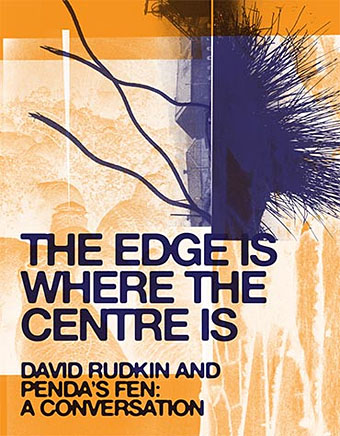

The Edge Is Where The Centre Is, the first book devoted to this visionary and never-commercially-released film, has at its heart a rare and far-ranging interview with Rudkin (b. 1936), a writer who for more than fifty years has, in the words of Gareth Evans, “charted a vast topology of viscerally-realised primary narratives for our troubled times”. It also features new essays by its editors — Gareth Evans, William Fowler and Sukhdev Sandhu – that explore the film’s status as a radical horror film, an experimental topography, a work that anticipates subsequent political debates about Englishness. (more)

What could be more essential than a book (and poster) devoted to my No. 1 Cult Thing Of All Time? My copies are already on order. Even better, this is a publication from the same team—editor and designer—that produced The Twilight Language of Nigel Kneale last year, a celebration of another British television dramatist that sent me on a full-scale re-viewing of Kneale’s major works.

There’s no need to enthuse about Penda’s Fen when I did all that four years ago but there’s a couple of points worth making in the light of this publication. The first is that it’s surprising that a wider reappraisal of Rudkin and Clarke’s film has lagged behind the resurrection of so many other British TV dramas, especially those that deal with rural horror, those that share a mythic resonance or impart an atmosphere of dread. Surprising because almost all the recent resurrections—the BBC ghost films (one of which was written by Rudkin), Robin Redbreast, The Children of the Stones, etc.—are primarily entertainments with little subtextual meat on their bones. That’s not to say that a subtext can’t be found if you apply the usual academic tools but Alan Garner’s adaptation of Red Shift is one of the few films of this school that has much going on under the surface.

Penda’s Fen doesn’t need a subtext when so much of its polemic is out in the open. It’s one of the most interesting of these films in being so directly political on several levels at once, even when it’s also being directly metaphysical: a call for disobedience and nonconformity on a sexual as well as a social level that (unlike Ken Loach et al) manages to generate a succession of indelible images.

This leads to the second point, the comparison made above to Lindsay’s Anderson’s If…. The similarity between the two films has always been unavoidable for me when If…. is another film that sits at the top of the cult list (see this post). Both films share a rejection of school and society, and also share an approach to sexuality that was very unusual for the late 60s/early 70s. The difference between the two films lies in their conclusions: If…. ends with riot and massacre, and while this may be a cathartic moment Lindsay Anderson wrote in the published script: “It doesn’t look to me as though Mick can win. The world rallies as it always will, and brings its overwhelming firepower to bear on the man who says ‘No.'” By contrast, Stephen in Penda’s Fen defeats his mental demons. If the final shot is of him walking down the hill into darkness we can at least feel he’s on his way to a better life. “Cherish the flame.”

The Edge Is Where The Centre Is is limited to only 200 copies so if you’d like a copy I’d suggest you place your order now.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Afore Night Come by David Rudkin

• White Lady by David Rudkin

• The Horror Fields

• Robin Redbreast by John Bowen

• Red Shift by Alan Garner

• Children of the Stones

• Penda’s Fen by David Rudkin

• If….

• David Rudkin on Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr