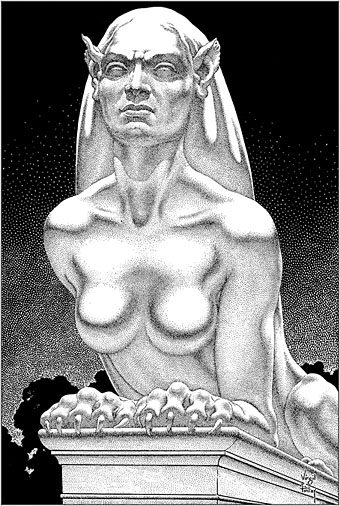

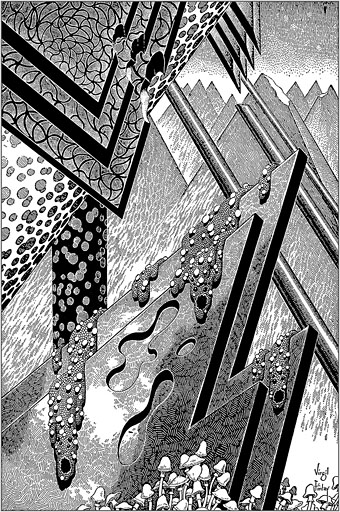

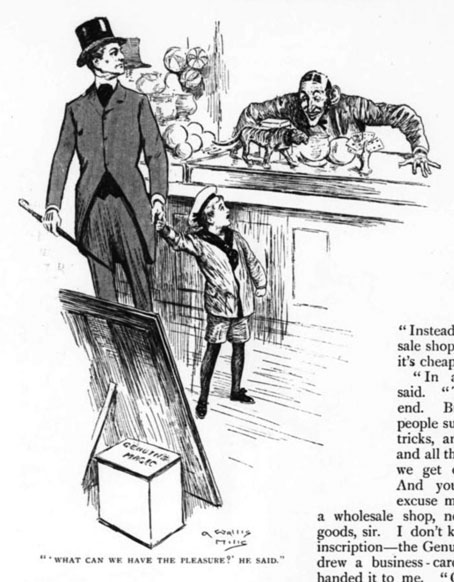

An illustration by Arthur Wallis Mills from The Strand Magazine, June, 1903.

I had not thought the place was there, to tell the truth—a modest-sized frontage in Regent Street, between the picture shop and the place where the chicks run about just out of patent incubators—but there it was sure enough. I had fancied it was down nearer the Circus, or round the corner in Oxford Street, or even in Holborn; always over the way and a little inaccessible it had been, with something of the mirage in its position…

Despite writing about an HG Wells adaptation only a week ago I hadn’t gone searching for more of them when this one turned up anyway, rather like Wells’ mysterious shop. I’d actually been looking at the filmography of the late Ian Emes, a director best known for the short animations he made for Pink Floyd’s concerts, although his career encompassed animated shorts like The Beard as well as longer films for television and the cinema. The Magic Shop, which was made in 1982, looks as though it might have been another of those shorts that used to be programmed as supporting titles for first-run features in British cinemas. Andrew Birkin’s Sredni Vashtar was one of these, a film which is also under 30 minutes in length and an adaptation of a popular piece of Edwardian fiction.

HG Wells’ story was first published in The Strand Magazine in June 1903 then collected in Wells’ Twelve Stories and a Dream a few months later. It’s been one of my favourite Wells stories since I first read it at the age of 11, as I mentioned in this review of the 1964 TV version. Wells’ fantasy reached me just as I was beginning to get very interested in conjuring tricks. I’d also been reading Victorian ghost stories in the reprint collections being published by Puffin and Lion, so a story about a shop that sold magic tricks, where the premises and proprietor had a slightly sinister quality, was exactly the kind of thing I wanted to read.

Ian Emes’ adaptation is a more successful Wells film than The Door in the Wall, and a much better adaptation of the story itself than the attempt to update the tale for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, but Emes still doesn’t really capture the spirit of the story. The main flaw is that the actor playing the boy who wants to explore the shop is too old for the role. The narrator’s son in the story is around five or six years old, and much of the tension in the telling comes from the way that the boy sees everything that’s happening as delightful and magical while the father experiences rising alarm at the unfolding events and the situation in which the pair find themselves. The second half of the story, in which father and son are led by the shopowner into the labyrinthine warehouse behind the shop, is also lacking. Emes’ production may have been compromised by its budget but there’s no sign of the surprises that you might have expected to be filmed by a former animator. Derek Jarman regular Karl Johnson plays the father, Ron Cook is the shopowner, and there’s a cameo near the beginning from William Rushton as the man whose whining son is denied admittance to the shop. (Rushton had earlier provided the voice of the afflicted shaver in The Beard.) At the end of Emes’ film father and son find themselves teleported to what looks like a back street somewhere near the river instead of being returned to a busy London street. This reminds me that the first time I visited Regent Street myself at the age of 13 I had half a mind to go looking for the “Genuine Magic Shop”—or to try and identify the place where it might have been. The elusive nature of Wells’ establishment makes it the forerunner of the chemist shop owned by the malevolent Grail-seekers in Charles Williams’ War in Heaven, which makes me wonder now whether Williams borrowed the idea from Wells.

Ian Emes’ film may be seen at his Vimeo channel (log-in required, or you can use the Vimeo app). The story can be found in a collection of fifty-four of Wells’ short stories at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Door in the Wall, 1956

• Claude Shepperson’s First Men in the Moon

• The Beard, a film by Ian Emes

• Uncharted islands and lost souls

• Doctor Moreau book covers

• The Island of Doctor Moreau

• Harry Willock book covers

• The Time Machine

• The Magic Shop by HG Wells

• HG Wells in Classics Illustrated

• The night that panicked America

• The Door in the Wall

• War of the Worlds book covers