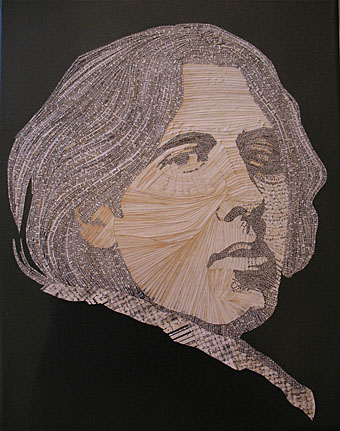

How to combine two recent {feuilleton} obsessions? Ask whether Oscar Wilde had his voice recorded on an Edison machine at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, 1900. It’s a tantalising question. We know from Wilde’s letters that he visited the Exposition several times; he talked with Rodin and admired a self-portrait by his old painter friend Charles Shannon in the British pavilion. Edison staff were prominent at the exposition and did us a favour by filming parts of it. Several of the Wilde biographies mention the rumoured recording, the details of which are recounted at Utterly Wilde:

According to H Montgomery Hyde’s 1975 biography of Oscar Wilde: “…It was during one of these visits to the Exhibition that Wilde was recognized in the American pavilion, where one of the stands was devoted to the inventions of Thomas Edison. One of these inventions was the ‘phonograph or speaking machine,’ and Wilde was asked to say something into the horn of the recording mechanism. He responded by reciting part VI of The Ballad Of Reading Gaol, which consists of the last three stanzas of the poem, and identifying it with his name at the end.” (More.)

The purported wax cylinder is lost but an acetate copy surfaced in the 1960s. Wilde’s son, Vyvyan Holland, identified his father’s voice then changed his mind later on. An analysis by the British Sound Archive threw further doubt on the recording so we’re left to make up our own minds which you can do for yourself here. It doesn’t sound to me like the voice one would expect from a man of Wilde’s physical size, but then I also never expected Aleister Crowley’s voice to be so highly-pitched. If anyone knows of more recent research or detail about the Wilde recording, please leave a comment.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive