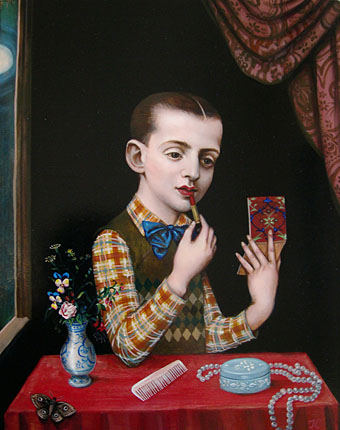

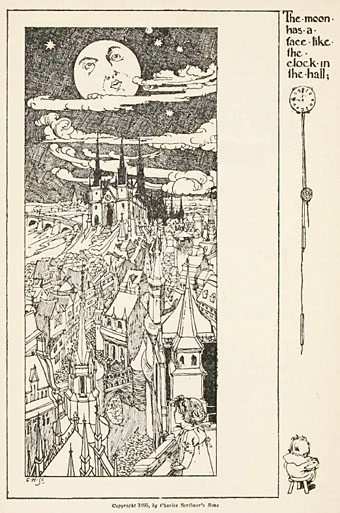

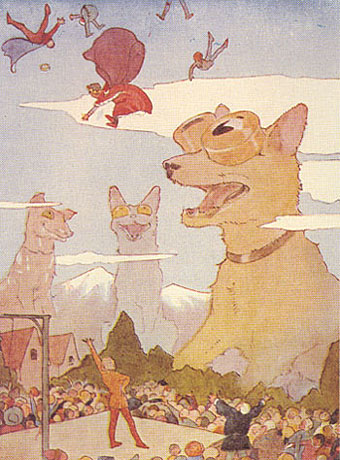

HJ Ford (1894).

“Do you see that great tree!” quoth the witch; and she pointed to a tree which stood beside them. “It’s quite hollow inside. You must climb to the top, and then you’ll see a hole, through which you can let yourself down and get deep into the tree. I’ll tie a rope round your body, so that I can pull you up again when you call me.”

“What am I to do down in the tree?” asked the soldier.

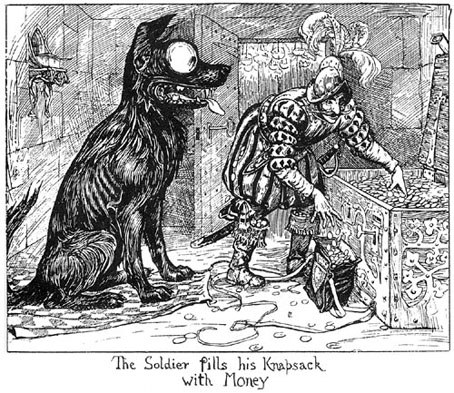

“Get money,” replied the witch. “Listen to me. When you come down to the earth under the tree, you will find yourself in a great hall: it is quite light, for many hundred lamps are burning there. Then you will see three doors; these you can open, for the keys are in the locks. If you go into the first chamber, you’ll see a great chest in the middle of the floor; on this chest sits a dog, and he’s got a pair of eyes as big as two tea-cups. But you need not care for that. I’ll give you my blue-checked apron, and you can spread it out upon the floor; then go up quickly and take the dog, and set him on my apron; then open the chest, and take as many farthings as you like. They are of copper: if you prefer silver, you must go into the second chamber. But there sits a dog with a pair of eyes as big as mill-wheels. But do not you care for that. Set him upon my apron, and take some of the money. And if you want gold, you can have that too—in fact, as much as you can carry—if you go into the third chamber. But the dog that sits on the money-chest there has two eyes as big as the round tower of Copenhagen. He is a fierce dog, you may be sure; but you needn’t be afraid, for all that. Only set him on my apron, and he won’t hurt you; and take out of the chest as much gold as you like.”

The Tinderbox (1835) by Hans Christian Andersen

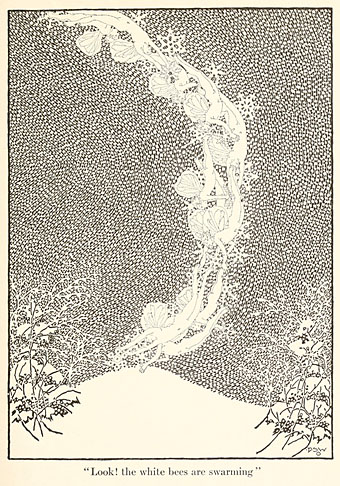

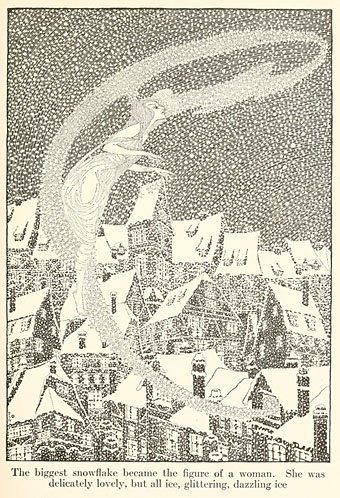

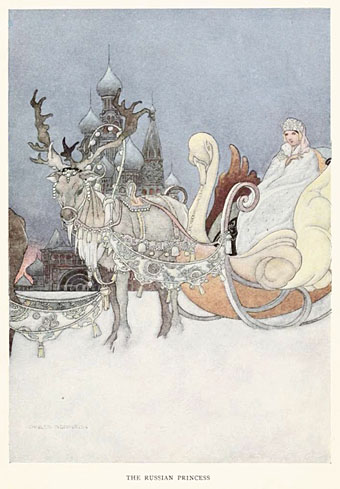

Helen Stratton (1910?)

Will at 50 Watts is to blame for this one, the illustrations he posted last week were excessive enough to give even a master of exaggeration like Tex Avery second thoughts. Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales have proved so popular over the years that a core group of stories tend to drive out the less familiar works from fresh editions. The Tinderbox is one of these minor stories, the tale of a soldier with a magic tinderbox capable of summoning a trio of supernatural dogs with enormous eyes. My first contact with the story was via a German television adaptation, Das Feuerzeug, filmed in 1958 and later screened in the UK as filler for the children’s TV schedule along with that memorably creepy series (also from Germany), The Singing Ringing Tree. I remembered little about the story but was never able to forget those weird dogs even though their eyes in the TV version are nothing like the way they’re presented in illustrations. They may not be as freaky but the way they’re presented as huge and black makes me think now of the ghostly barghests or black dogs of British folklore.

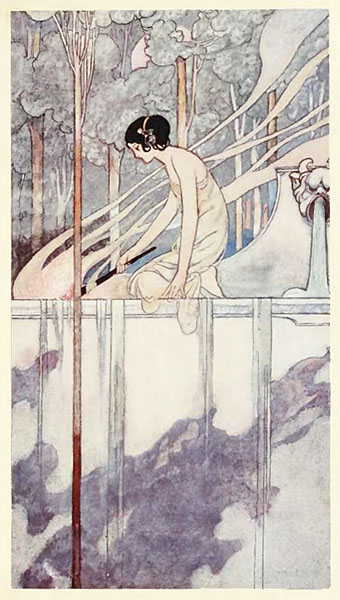

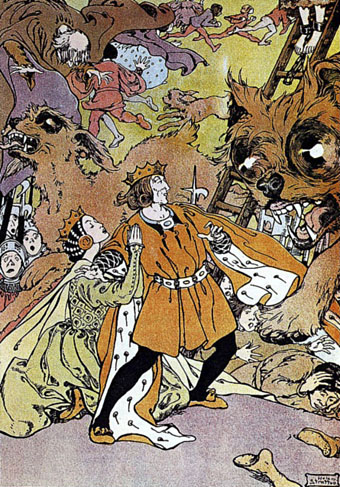

Searching around for illustrations turned up the handful here. Many illustrators concentrate on other scenes but I’ve only been looking for the dogs. I’m sure there’s more to be found so this may well be a subject to revisit later. The Stratton and Tarrant pictures show the climax of the story when the soldier, about to be hanged for having used the dogs to kidnap a princess, summons his creatures to kill the king, queen and all the people who condemned him. Yes, it’s good wholesome fare for kids.

Margaret Tarrant (1910).