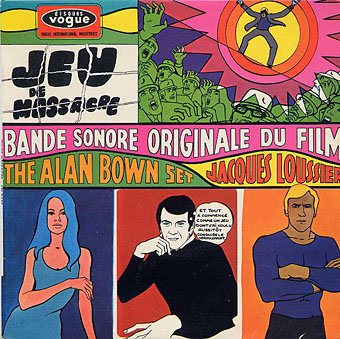

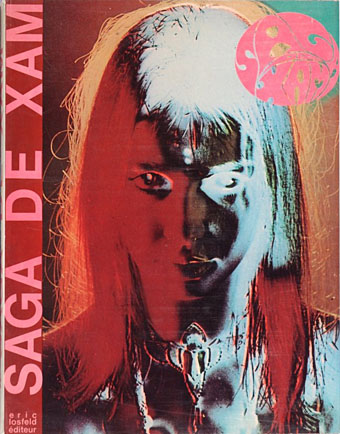

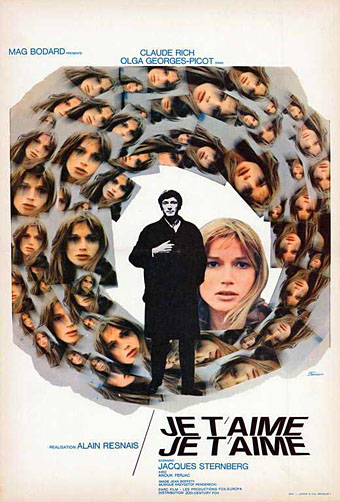

Design by René Ferracci.

Continuing an occasional series about artworks in feature films with a return to Alain Resnais. This one is less substantial than the Providence post, but 2022 happens to be the director’s centenary year, and this particular film, like Providence, is worthy of greater attention.

Last Year at Marienbad is occasionally proposed as science fiction of a very rarified sort (JG Ballard thought it was) but there’s no question about the SF credentials of Je t’aime, Je t’aime (1968), a drama that uses time travel to explore a troubled romantic relationship. Claude Ridder (Claude Rich), an unattached, suicidal man, is persuaded by scientists to assist with a potentially hazardous experiment. He agrees to a one-minute excursion into his past but the experiment doesn’t work as intended, causing him to be caught between the present—in which he can’t escape from a womb-like time machine—and his recent past, in which he relives brief moments without any awareness during the return period of their being a part of the experiment. The flashbacks that comprise most of the film’s running time show us a random sequence of the events leading to Claude’s suicide attempt, the end result of his relationship with his terminally ill partner, Catrine (Olga Georges-Picot).

The time machine.

Despite the presence of a time machine and a script by Jacques Sternberg, a Belgian science-fiction writer, Resnais was adamant that Je t’aime, Je t’aime wasn’t a science-fiction film. This is the kind of comment guaranteed to annoy the more zealous SF reader but it’s true in the sense that the film isn’t about time travel or time machines per se; the temporal experiment is a device to allow the non-linear exploration of a human drama that’s the real concern of director and writer. Previous Resnais films had dealt with remembrance of one sort or another, often using flash cuts to juxtapose different moments or scenes remembered or imagined. Je t’aime, Je t’aime pushes these techniques to an extreme, showing us every facet of the Claude/Catrine relationship, from initial meeting to tragic end. The narrative fragmentation isn’t so surprising today but it was a radical step in 1968, one that proved commercially unsuccessful.

In addition to having a Belgian writer, Je t’aime, Je t’aime is mostly set in Brussels, so the art this time is a famous Belgian painting, one of the many versions of The Empire of Light by René Magritte, which appears in the scenes in Claude’s apartment.

In other hands this might be an incidental decoration but, as Providence demonstrates, Resnais was a director who enjoyed significant details, even if the signification isn’t always obvious. The Magritte painting serves two functions: its slow migration from one side of Claude’s apartment to the other (and the appearance of other pictures around it) shows the passage of time from one flashback to the next.