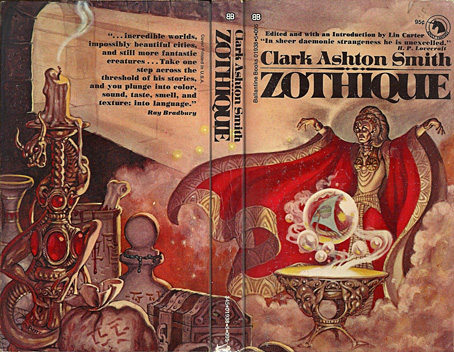

Cover art by George Barr, 1970.

A few years ago I wrote a short piece about Virgil Finlay’s illustrations for a Zothique story by Clark Ashton Smith, The Garden of Adompha, so this post may be regarded as a more substantial sequel. If Smith remains something of a cult author then Zothique is the pre-eminent cult creation from his career as a writer of weird fiction. Most of Smith’s stories can be grouped together according to their location: Atlantis, Hyperborea, Averoigne in medieval France, the planet Mars, and so on. Zothique was a more original conception than his other worlds, being the last continent on Earth in the final years of the planet, an idea which had precedents in earlier novels such as William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land but which hadn’t been used before as a setting for a cycle of stories. The distant future suggests science fiction but, as with the Zothique-influenced Dying Earth of Jack Vance, science and technology is long-forgotten and sorcery rules the day. The poetry that Smith wrote before he took to writing short stories had a distinctly Decadent quality—”like a verbal Gustave Moreau painting“—and Zothique is a richly Decadent world, with the entire planet in a state of decay along with its barbarous, demon-worshipping peoples.

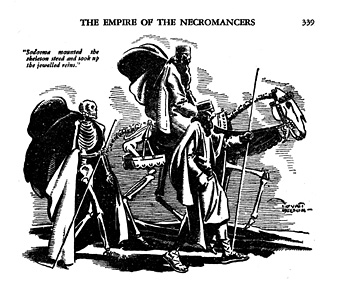

Weird Tales, September 1932. Art by T. Wyatt Nelson.

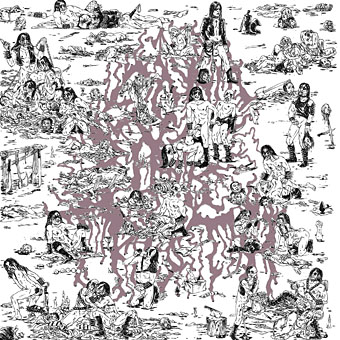

All the Zothique stories had their first printings in Weird Tales, a magazine that ran illustrations with most contributions, but unless you’re a pulp collector many of the illustrations have been difficult to see until very recently. One of the pleasures of looking through fiction magazines is seeing how their stories might have been illustrated when they were first published. Popular tales eventually find their way into book collections but their illustrations tend to be marooned in the titles where they first appeared unless the artist is of sufficient merit to warrant a collection of their own.

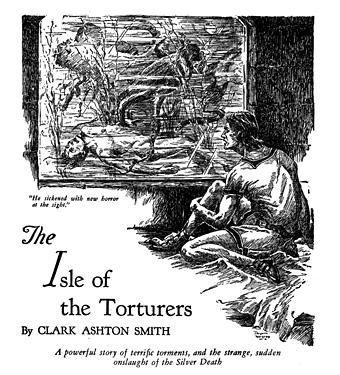

Weird Tales, March 1933. Art by Jayem Wilcox.

The examples here are all from recent uploads at the Internet Archive which now has a complete run of Weird Tales from 1923 to 1954. The illustrations also run in order of publication with links to the relevant issues, although I agree with Lin Carter’s ordering of the stories. Smith never organised them himself, and the later reprints from Arkham House and others tend to scatter them through separate volumes. When Lin Carter edited the Zothique collection in 1970 he put the stories into an order that follows the very loose chronology running through the cycle.

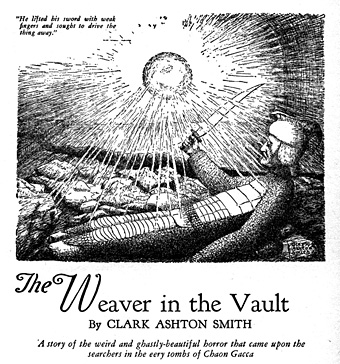

Weird Tales, January 1934. Art by Clark Ashton Smith.

One surprise of this search was discovering that Smith himself had provided illustrations for several of the stories. Some Smith enthusiasts like his drawings and paintings but I’m afraid I’m not among them, his sculpture work is better. It’s doubtful that these would have been printed at all if they weren’t the work of the author.