There are always more Golems…

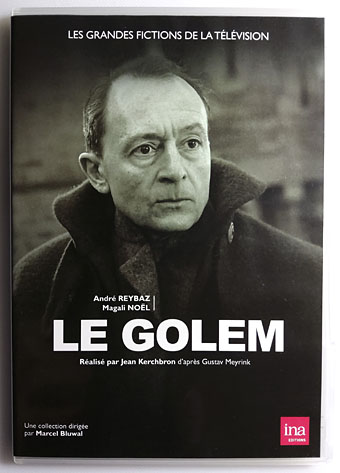

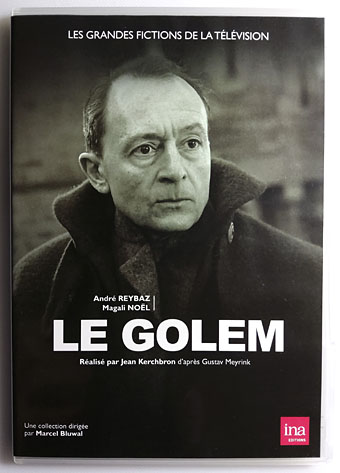

Le Golem is a 110-minute film based on Gustav Meyrink’s novel which hasn’t received as much attention as you’d expect considering the dearth of Meyrink adaptations. The production was for French TV so its obscurity may be a result of unavailability as much as anything else, television being a medium notorious for burying its own history. The DVD I was watching is an official release from INA with no subtitles (merci!), but English subs may be found online.

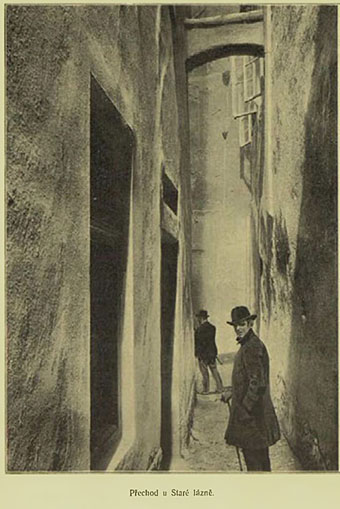

Meyrink’s novel isn’t an obvious choice for film or television adaptation despite the popularity of the Golem theme. His story is an uneven blend of mysticism and melodrama related via many digressions and rambling conversations. The title and the Prague setting suggest Paul Wegener’s Der Golem (1920), with the ghetto monster dominating the proceedings, but Meyrink’s Golem remains in the shadows (if it exists at all), being more of a symbol for the mystical and psychological challenges that beset Athanasius Pernath, the novel’s protagonist. Given all this I’m curious to know who decided to adapt the story when there’s so much about the film that would confuse an audience who hadn’t read the novel. The opening scenes move rapidly from a stylised city of the 1960s to the Prague ghetto of the past while omitting the attempts of Meyrink’s narrator to make sense of his situation. A note on the DVD states that the film was broadcast at 8:30pm on the national channel, ORTF, which makes its peculiarities even more surprising.

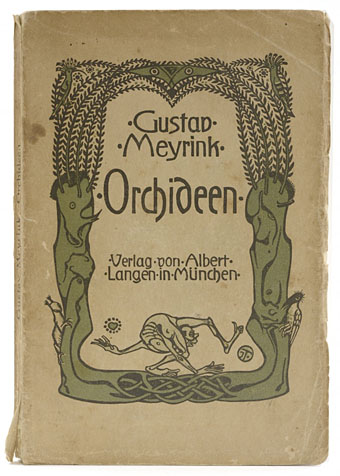

The director, Jean Kerchbron, spent much of his career filming adaptations of classic plays and stories for French television, ranging from adventure serials to Molière and Shakespeare. Writer Louis Pauwels was co-editor with Jacques Bergier of the popular Planète magazine, a journal of fantasy, science fiction and scientific speculation, but had little experience in the film world; Le Golem was his first feature for which he supplied the dialogue and adapted the story with Kerchbron. Pauwels and Bergier are names familiar to Anglophone readers of Fortean literature for The Morning of the Magicians (1960), their discursive treatise on “Fantastic Realism” whose success launched Planète and later gave David Bowie some ideas for lyrics. The pair refer to Meyrink in their book as a “neglected genius” prior to running an extract from one of the author’s later novels, The Green Face. Pauwels and Kerchbron manage to condense the work of the neglected genius without doing too much harm to his story, compressing some sections (a request for an explanation in a later scene is wisely rejected as “too complicated”) while omitting the overly mystical episodes that might have posed problems for a limited budget. Pauwels moves what’s left of the mysticism to Pernath’s philosophical voiceovers. Kerchbron’s direction is lively and much more elliptical than is usual for the plodding television medium. Novel and film only depart near the end when various plot threads are hastily tied together.

Continue reading “Le Golem, 1967”