(Pynchonian? Pynchonesque? Pynchon-heads can no doubt supply the most common descriptor but for now Pynchonian will do.)

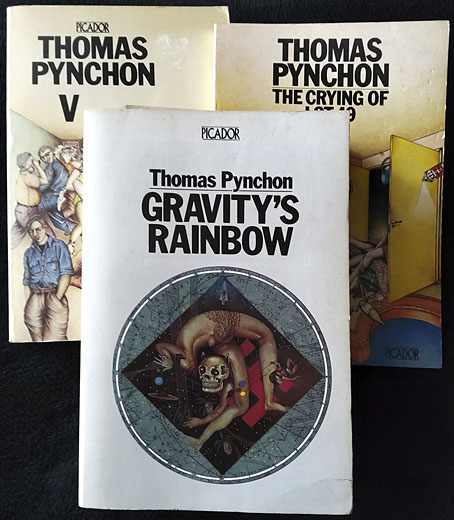

Is it possible to identify a Pynchonian strand in cinema? This question came to mind while I was reading the end of Gravity’s Rainbow, and probably a little before then during a scene that takes place in the Neubabelsberg studio in Berlin. The Pynchon reading binge is still ongoing here—after finishing the Rocket book I went straight on to Vineland, and I’m currently immersed in Mason and Dixon—so I’ve been watching films that complement some of the preoccupations in the Pynchon oeuvre, at least up to and including Vineland. This is a small and no doubt contentious list but I’m open to further suggestions. Inherent Vice is excluded, I’ve been thinking more of films that are reminiscent of Pynchon without being derived from his work. Elements that increase the Pynchon factor would include: a serio-comic quality (essential, this, otherwise you’d have to include a huge number of thrillers); detective work; paranoia; songs; and a conspiracy of some sort, or the suspicion of the same: a mysterious cabal–the “They” of Gravity’s Rainbow—who may or may not be manipulating the course of events.

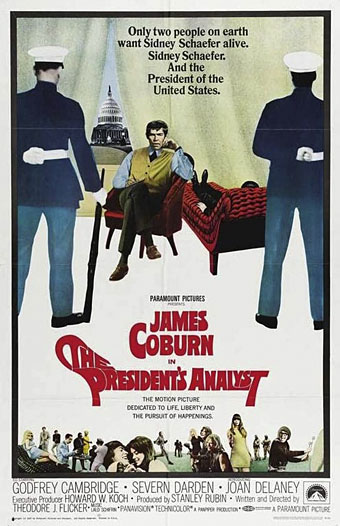

The President’s Analyst (1967)

I’d be very surprised if Pynchon didn’t like this one. James Coburn as the titular analyst, Dr Sidney Schaefer, has little time to enjoy his new job in Washington DC before half the security services in the world are trying to kidnap him to discover what he’s learned about the President’s neuroses. This in turn leads the FBI FBR to attempt to kill Schaefer in order to protect national security. Pynchonian moments include a bout of total paranoia in a restaurant, Canadian spies disguised as a British pop group (“The ‘Pudlians”), and a visit to the home of a “typical American family” where the father has a house full of guns, the mother is a karate expert, and the son uses his “Junior Spy Kit” to monitor phone conversations. Later on, an entire nightclub gets spiked with LSD. This is also the only film in which someone evades abduction to a foreign country by the cunning use of psychoanalysis.

Is it serio-comic? Yes.

Is there detection? In the background: the CIA CEA and KGB agents have to work together in order to outwit the FBI FBR and discover who the ultimate villains might be.

Is there paranoia? You only get more paranoia in one of the serious conspiracy dramas of the 1970s like The Conversation or The Parallax View. (The latter includes the same actor who plays the All American Dad, William Daniels.)

Any songs? Yes. Coburn hides out for a while with the real-life psychedelic group Clear Light, and helps with their performance in the acid-spiked nightclub.

“They”? There are multiple “They”s in this one.

Pynchon factor: 5. Maybe a 6 for the LSD.