Historia Naturae, Suita (1967).

Another very welcome DVD release from the BFI. Svankmajer’s shorts have always been my favourites of his film work. I love his Alice feature film (for me, the best screen adaptation of Alice in Wonderland), and Faust (although the jabbering devils get annoying) but on the whole his longer films don’t seem to work as well as the earlier works. The short films present his Surrealist intentions in their purest expression, whether using his own jerky form of stop-motion animation or the aggressive montage seen in The Ossuary and elsewhere.

As with the Brothers Quay release from last year, there’s a great set of extras with this. If you’re curious about the films but have never seen them, searching for his name on YouTube turns up a few examples.

The most comprehensive DVD collection ever assembled of all 26 short films by the legendary Czech Surrealist filmmaker-animator Jan Svankmajer is released by the BFI on 25 June. Technically and conceptually astonishing in their own right, these films are also as remarkable for their philosophical consistency as for their frequently mind-boggling imagery.

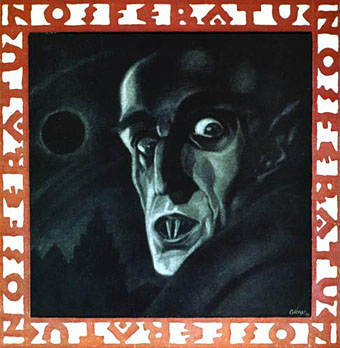

Drawing on a tradition of Surrealism based in the capital of magic and alchemy—Prague—Svankmajer uses a range of techniques, combining live action, puppet theatre, stop-motion and drawn animation, claymation, cut-outs, re-edited archive footage and montage.

With nearly eight hours of material, compiled on three discs and packaged in a deluxe digipack with a 56-page illustrated booklet, the DVD is a truly must-have item for any Svankmajer fan. Its release follows a visit by the director to BFI Southbank on 29 May to discuss his work, after a preview of his latest film Lunacy. Lunacy opens for a two-week run on 1 June, part of a complete Jan Svankmajer retrospective season at BFI Southbank from 1–16 June, a selection of which will then go on tour.

Compiled by BFI Screenonline’s Michael Brooke, who also produced last year’s highly acclaimed release Quay Brothers: The Short Films 1979–2003, the DVD collection spans almost 30 years, from The Last Trick (1964) to Food (1992). All the classics are included—Punch and Judy, The Flat, Jabberwocky, Dimensions of Dialogue, Down to the Cellar and both versions of The Ossuary (with the original banned tour-guide soundtrack and the replacement music track), alongside many British video premieres. It even contains the music video made for former Stranglers front man Hugh Cornwell (Another Kind of Love) and two ‘Art Breaks’ created for MTV.

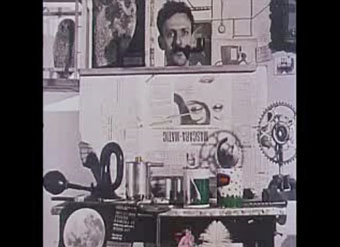

The third disc of two-and-a-half hours of extra material includes a bonus short, Johanes Doktor Faust (1958); the original 54-minute version of The Cabinet of Jan Svankmajer (1984) with a brand new introduction by the Quay Brothers; the French documentary Les Chimères des Svankmajer (2001); interviews with Jan and Eva Svankmajer and examples of their work in other media. There’s also a chance to see some Svankmajer special effects, created for commercial Czech features when he was banned from making his own films. The 54-page booklet includes an introduction to Svankmajer by Michael O’Pray; detailed film notes by Michael Brooke, Simon Field, Michael O’Pray, Julian Petley, A.L. Rees and Philip Strick; notes on the extras and much more.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Short films by Walerian Borowczyk

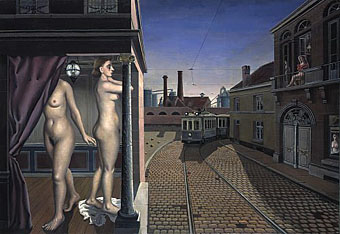

• Taxandria, or Raoul Servais meets Paul Delvaux

• The Brothers Quay on DVD

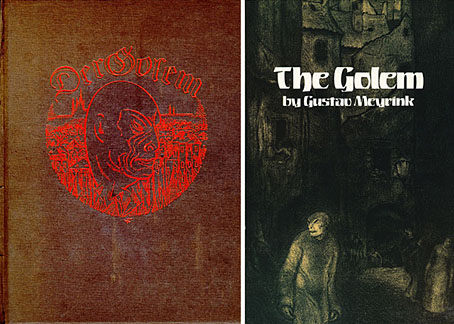

• Barta’s Golem