Checkerboard and Playing Cards (1915) by Juan Gris.

Happy new year. 02015? Read this.

Composition No. 23 (1915) by Jacoba van Heemskerck.

The Double Dream of Spring (1915) by Giorgio de Chirico.

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Checkerboard and Playing Cards (1915) by Juan Gris.

Happy new year. 02015? Read this.

Composition No. 23 (1915) by Jacoba van Heemskerck.

The Double Dream of Spring (1915) by Giorgio de Chirico.

A Glove: Anxieties (1881) by Max Klinger.

Although the Glove‘s scenario was given its due Germanic explication by contemporary critics, it defies rational analysis. The last picture, which was seen as a kind of happy ending to the glove’s peregrinations, is particularly ambiguous and leaves the whole meaning of the series in doubt. The story is a parable of loss based on a trivial lost article, like the lost keys in Bluebeard and in Alice, like Desdemona’s missing handkerchief, or like the philosopher’s spectacles in Klinger’s own Fantasy on Brahms, which have slid out of their proprietor’s reach just as he was nearing the summit of a kind of Matterhorn. There are overtones of erotic symbolism and fetishism in the glove and the phalloid monster who abducts it, heightened for a modern viewer by the Krafft-Ebing period costumes and décors (the engravings appeared in 1881, and the drawings were apparently finished in 1878).

John Ashbery describing Max Klinger’s extraordinary series of etchings A Glove (aka Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove) which in their inexplicable narrative of fetishist obsession anticipate Surrealism. See the entire sequence here or here. For A Glove in print there’s The Graphic Works of Max Klinger from Dover Publications.

The Song of Love (1914) by Giorgio de Chirico.

Ashbery begins by discussing Giorgio de Chirico’s enthusiasm for Klinger’s work, a passion and influence that provides one of the many connections between the Symbolists and the Surrealists. This “metaphysical” painting looks back to Klinger and forward to Magritte.

The Pleasures of the Glove, 3 (1974) by Duane Michals.

The enigmatic encounter of ‘The pleasures of the glove’ follows the lead character as he fantasises about a pair of gloves on the hands of a mannequin in a shopfront window. The perverse pleasure of desiring the gloves but not acquiring them leads him on a surreal adventure of first imagining his own glove as a queer furry tunnel that swallows his hand to the fantasy of stroking the naked body of a woman he sees on the bus with her own glove. (more)

A more contemporary take on the same idea, albeit without the intercession of a pterodactyl-like thief. If Klinger is pre-Surrealism then this is the post- version; Michals photographed René Magritte, and many of his other works run in a distinctly Surreal direction. (Thanks to Anne Billson for the tip!)

The Vanished World of Gloves (1982) by Czech animator Jiri Barta features sex, Surrealism and a lot more besides, all in the space of 16 minutes. A can of film is unearthed which contains a series of short episodes pastiching different cinematic styles: Chaplinesque slapstick, swashbuckling romance, Buñuel Surrealism, a war film, a Fellini orgy and a science fiction apocalypse. All the parts are played by gloves, of course, and if you didn’t see the credits you might take this at first for a Svankmajer short.

The Vanished World of Gloves: part one | part two

Update: I knew I’d forgotten something… Added de Chirico’s The Song of Love.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• More Golems

• Max Klinger’s New Salomé

• Barta’s Golem

René Magritte as portrayed by Patrick McDonnell.

René Magritte died in 1967, the year Eric Duvivier’s La femme 100 têtes appeared in French cinemas. Magritte is even less visible cinematically than Max Ernst, IMDB lists a couple of documentaries and nothing else. There are trace elements elsewhere, notably the Magritte and de Chirico influence in Bertolucci’s Borges’ adaptation The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), but the artist’s arresting visual imagination has always found more of a welcome on book covers than cinema screens.

One exception is David Wheatley’s drama documentary René Magritte (1976), yet another work you won’t find listed at IMDB. This was Wheatley’s graduation film which the BBC screened in a 30-minute version (shorn of some apparently clunky dialogue scenes) in 1979, and which secured for Wheatley a place as a regular director for the BBC’s Omnibus and Arena arts programmes. I saw the 1979 broadcast, and caught it again a decade later when one of the channels was having a season of Magritte-related programming, something that’s impossible to imagine in today’s debased television landscape.

For a student film it’s a stunning piece of work, taking a similar approach to Eric Duvivier in bringing to life many of the artist’s more famous pictures: a window shatters to reveal the scene behind it painted on its panes, a mountain hovers ponderously over the sea, a dove made of clouds flies across a stormy sky. Between the artworks there are short biographical scenes. There’s a sole version of the film on YouTube that remains watchable despite being a low-quality recording from video tape that’s also hacked into three parts and subtitled in Danish.

Looking for more information about David Wheatley it was dismaying to find he’d died in 2009, aged 59. Leslie Megahey—a cult TV director of mine—wrote an obituary for the Guardian where he describes some of Wheatley’s other productions including the Arena film Borges and I (1983)—as far as I’m aware the only British TV documentary about Jorge Luis Borges—and Wheatley’s first feature film, an adaptation of Angela Carter’s The Magic Toyshop (1987). I recall enjoying the latter, produced at a time when the success of The Company of Wolves (1984) made it seem there might also be a place in the cinema for Angela Carter’s imagination; we know how that worked out. The Magic Toyshop doesn’t seem to have had a DVD release so good luck to anyone searching for it. As for René Magritte, if anyone runs across a better online copy be sure to leave a comment.

Previously on { feuilleton }

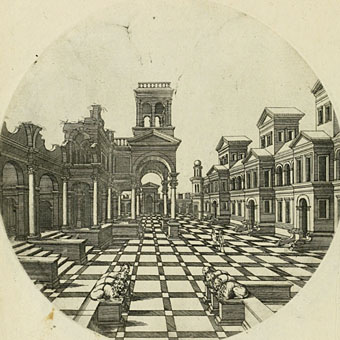

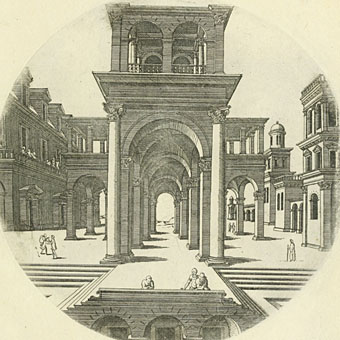

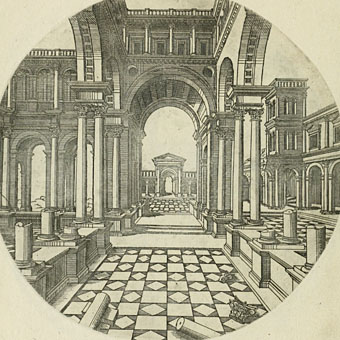

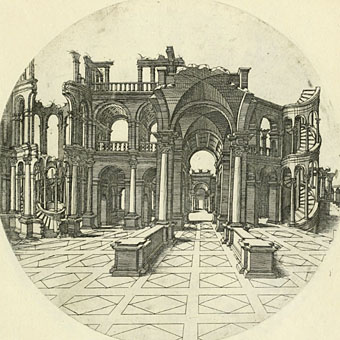

• The Public Voice by Lejf Marcussen

Something discovered following another delve through the collections of etchings and engravings at the Internet Archive where a frustrated search for one subject turns up something else. This 1549 folio of architectural engravings is credited to architect and designer Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1510–1584), and the plates are based on earlier renderings by Agostino Veneziano and Hieronymus Cock, he of the incredible map of the Americas. Among the details of columns and caryatids there’s a series of the kind of imaginary perspective views I always like to see, lots of sparsely-populated courtyards in various states of ruin. It’s easy to imagine these prospects being transformed into scenarios from Paul Delvaux or Giorgio de Chirico after a suitable change of lighting.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The etching and engraving archive

Townscape (1934).

Carel Willink was a Dutch painter whose self-described brand of “imaginary realism” conjured in its early years a collection of views of desolate plazas, empty lanes and abandoned ruins over which smoke or cloud hangs like an ominous portent. The works of Giorgio de Chirico and Paul Delvaux come to mind when looking at these pictures although Willink’s work has enough unique qualities to stand apart from his more famous contemporaries. I’m also reminded a little of Spanish artist Arnau Alemany who has a similar predilection for isolated architecture.

Chateau in Spain (1939).

There’s an official Willink website here, while further paintings can be seen at this Flickr set and also at Ten Dreams.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Bruges-la-Morte

• Taxandria, or Raoul Servais meets Paul Delvaux

• The art of Arnau Alemany