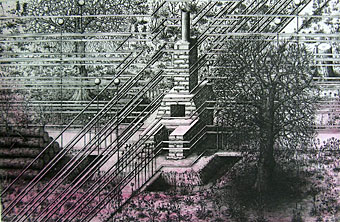

A (2002), etching.

During the last six years, British artist Paul Noble has invented a city. Named for its creator, Nobson Newtown comprises extremely large and meticulously crafted pencil drawings, each depicting a different building or location within Noble’s fictitious industrial town built on the edge of a forest. Although they are precisely rendered in realistic detail, Noble’s creations are much more than a feat in naturalistic representation. They embody the sly wit that characterizes the best of British satire. Each blocky construction is crafted out of a grouping of letters that identifies its owner or function. Each structure is then individually modified to take on the needs of its inhabitants in ways that often render its name unreadable. Representing a utopian vision gone awry, Nobson Newtown is a meditation on city planning, modernism, and life at the turn of the twenty-first century.

Noble’s work is currently on display at the Site Gallery, Sheffield (details below).

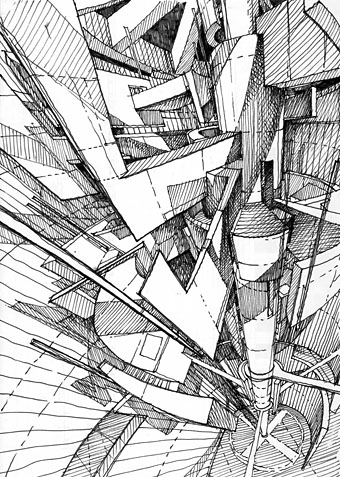

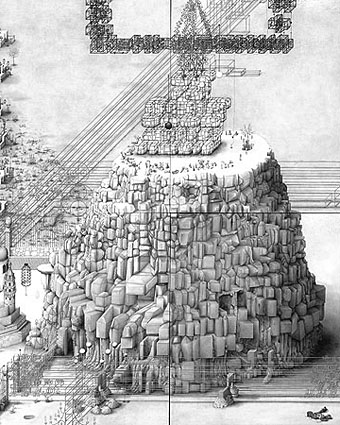

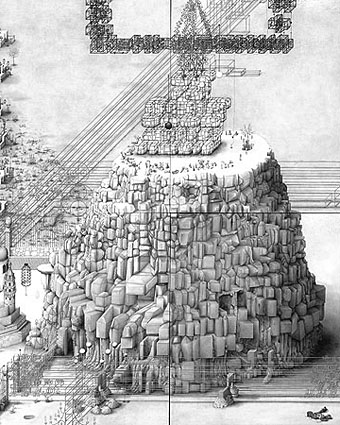

Ye Olde Ruin, (detail) (2003-04), pencil on paper.

In the City of Last Things

Katja Davar, Paul Noble, Torsten Slama

9 Sep–21 Oct 2006

Katja Davar, Paul Noble and Torsten Slama use drawing and animation to present projections of alternative urban and social possibilities. Skirting dystopia, perhaps closer to the literal meaning of utopia as ‘no place’ the artists project personal no places which blend flawed utopian fantasies and altered ecosystems and which question the possibilities for perfected urban-industrial societies.

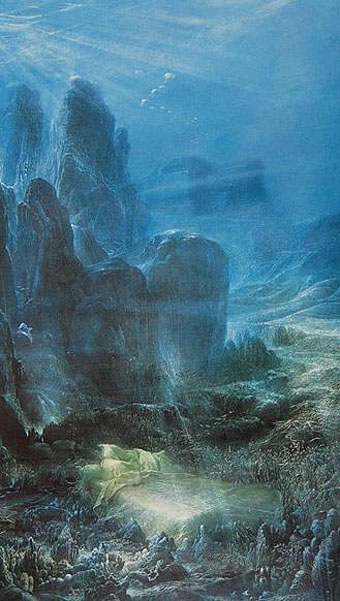

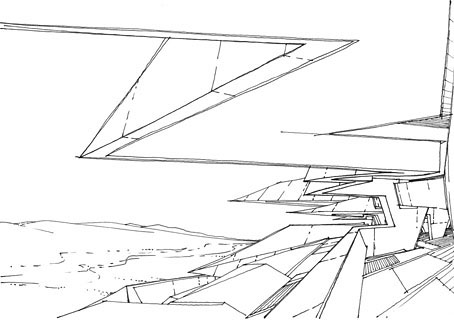

Forking Ocean Path is a new body of work by Katja Davar comprising 3D animation and large-scale drawings. These works address the self-destructive nature of mankind and posit a possible outcome. Making reference to Leonardo da Vinci’s treatise on water, which addresses the integration of land and sea, Davar presents an undersea world devoid of human life. In one animation, a creature, part marine and part machine, slowly floats upwards through the remnants of an industrial city at the bottom of the ocean. The imagery is poignant and the short, silent animation is an understated reminder of the precariousness of our civilisation and the force of natural phenomena. The animations are set within carefully designed three dimensional screens which enhance the enigmatic combination of traditional drawing and sophisticated computer-aided animation.

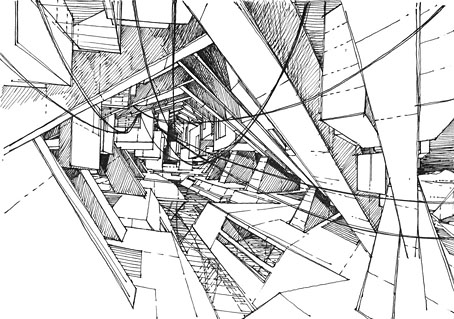

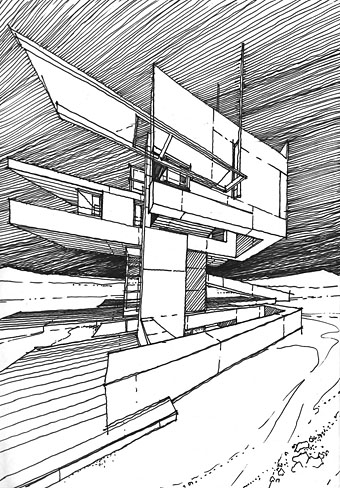

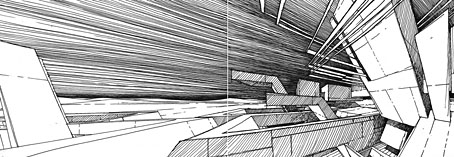

Paul Noble’s Unified Nobson is an animation that ‘unifies’ the various sections that make up Nobson Newtown, the fantastical town depicted through drawings on paper. Named for its creator, Nobson Newtown comprises extremely large and meticulously crafted pencil drawings, each depicting a different building or location within Noble’s fictitious industrial town. Modelled on the new towns devised in the early 20th century to create a perfect fusion of the urban and rural, the drawings offer aerial perspectives over a fantastical cityscape in which each blocky construction is crafted out of a grouping of letters that identifies its owner or function. Representing a utopian vision gone awry, Nobson Newtown is a meditation on city planning, modernism, and the possibilities for renewal within dysfunction.

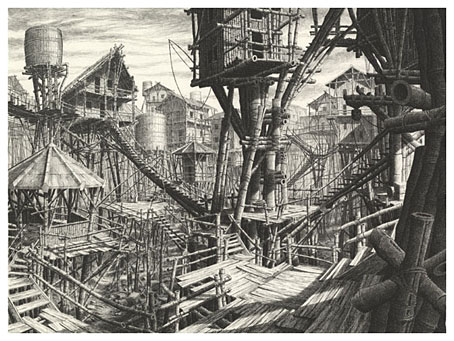

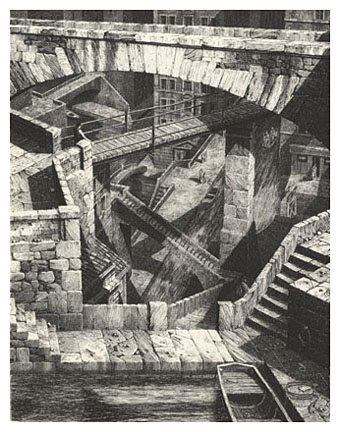

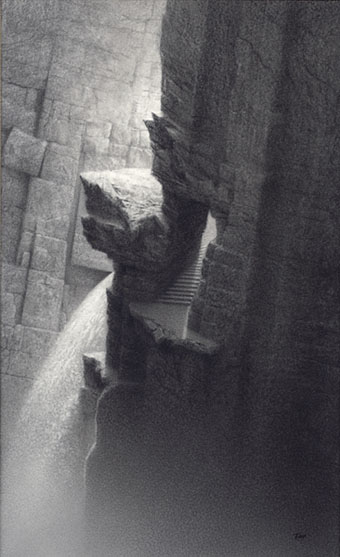

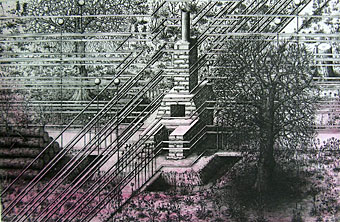

Torsten Slama’s coloured pencil drawings from the cycle Gardens of Machine Culture are inspired by Chinese paintings and recall the aesthetics of vintage science fiction. Modernist architecture and industrial constructions merge with rocky, cyclopean landscapes, sparsely grown with arboreal vegetation. Even if there are no humans on the scene; the buildings, just like the rocks and the muscular, sinewy trees function as their dignified, mineral or vegetable counterparts, as the individual personalities of which this civilisation constitutes itself. The depicted worlds are anti-cities in which industry and architecture, like the humans who built them, are part of an evolved nature.

The exhibition title references the dystopian city in Paul Auster’s novel In the Country of Last Things—’a haunting picture of a devastated futuristic world which chillingly shadows our own’ in which the ‘last things’ in the title refers not only to the disappearance of manufactured objects and technology but also the fading of memories of them and the words used to describe them.

Katja Davar was born in London and now lives and works in Cologne.

Paul Noble was born in Dilston, Northumberland and lives and works in London.

Torsten Slama was born in Schwarzach, Austria and lives and works in Berlin.

In collaboration with The Drawing Room, London.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Arnau Alemany

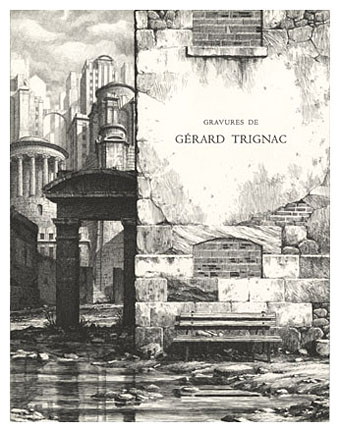

• The art of Gérard Trignac