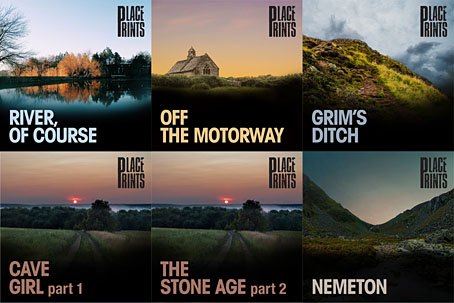

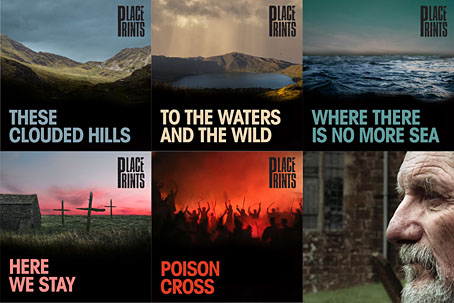

Hidden voices and haunted landscapes are conjured up in ten unique stories from the imagination of visionary writer David Rudkin. Join a stellar cast including Juliet Stevenson, Toby Jones, Josie Lawrence, Michael Pennington and Stephen Rea, among many others on an enlightening journey across the British Isles with this dramatic audio cycle that will transform your sense of the landscape around you.

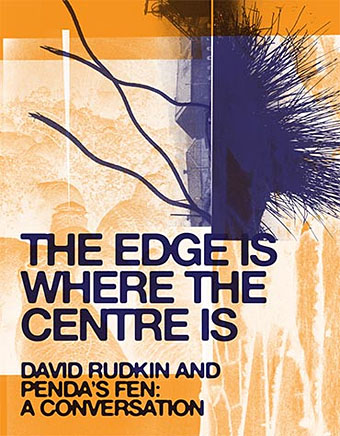

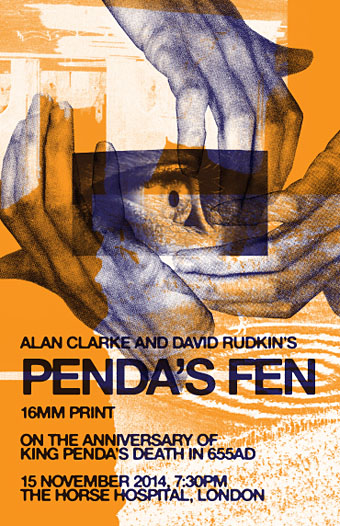

PlacePrints is the umbrella title for ten new audio plays by David Rudkin, a series directed by Jack McNamara for the New Perspectives theatre company. The series has been freely available online for over a year but only came to my attention last month. One of the pleasures of recent years has been seeing David Rudkin’s dramas being reappraised after many years of neglect, although interviews suggest the writer has ambivalent feelings about the concentration on the gaudier, generic elements of his surviving TV plays. In The Edge Is Where The Centre Is, a book by Texte und Töne about Penda’s Fen, Rudkin is determined to frame the film as a political work when most of the reaction to it over the past decade has been to label it “folk horror”. I can’t complain too much when I’ve been partly responsible for giving it the horror label in the first place, having written (at the request of one of the editors) a short review of the film for Horror: the Definitive Guide to the Cinema of Fear (2006), and later contributed a lengthy piece about Rudkin’s stage and TV dramas to Folk Horror Revival: Field Studies (2015). In my defence, the latter was intended to draw attention to Rudkin’s work as a whole, and you have to start somewhere. In 2006 Penda’s Fen and Artemis 81 were mysteries to most people, not horror enough for the MR James obsessives, or, in the case of Artemis 81, too weird for the science-fiction crowd; both of them were also unavailable in any form. Grant Morrison was the only person I’d met who not only knew who Rudkin was but had read the available playscripts. Some of Rudkin’s works may touch on generic horror or science fiction but even his adaptation for the BBC of The Ash-Tree by MR James can be grouped with his own dramas via its themes of religious conflict and the presence of history in the landscape. He also changes Mothersole’s warning from James’s “There will be guests at the hall!” to the pithier “Mine shall inherit!”, a threat delivered with a playwright’s economy, and a declaration whose reference to inheritance connects the film to a persistent Rudkin theme, the legacies of people, place and history.

All of which makes the existence of the PlacePrints dramas very welcome indeed. For the most part, these are closer to Rudkin’s theatrical works than his TV films, being a collection of lone voices engaging repeatedly with the legacies of people, place and history: a British Celt watching the invading Roman army build one of their roads across the Warwickshire fields (River, Of Course); a close description of a walk along an ancient pathway in Cornwall (Nemeton); the scathing voice of an earthwork following the clumsy searches of an aged academic (Grim’s Ditch); a young student slipping in and out of visions of life in Suffolk 30,000 years ago (Cave Girl/The Stone Age). The series features an impressive range of acting talent, especially Juliet Stevenson in Grim’s Ditch, and Frances Tomelty as an elemental spirit haunting the waters of Lough Fea in To the Waters and the Wild. Sympathetic sound design and music by Adam McCready adds a hint of location atmosphere and dramatic texture without ever being obtrusive. Each piece is preceded by an authorial introduction, one of which suggests that Rudkin may not be too displeased about being tagged with the horror label when he describes Grim’s Ditch as being a contemporary equivalent of an MR James warning to unwary academics. The episode has its share of uncanny moments, with Toby Jones as the professor receiving a lesson from the landscape that he won’t forget. The final recording is an interview with David Rudkin by Gareth Evans, one of the interviewers and contributors to The Edge Is Where The Centre Is.

There’s a further parallel in some of these pieces with chapters from Voice of the Fire by Alan Moore, a novel that also deals with (among other things) ancient Britain, the Roman invasion and the patterns of history. Fitting, then, that New Perspectives have produced the audio version of Voice of the Fire with the same director and sound designer, and with Toby Jones returning as one of the characters. I generally prefer to read books rather than to hear them read but I’m looking forward to listening to this one as well. (Thanks to Jay for the tip!)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Voice of the Fire

• Penda Reborn

• Folk Horror Revival: Field Studies

• The Edge Is Where The Centre Is

• Afore Night Come by David Rudkin

• White Lady by David Rudkin

• Penda’s Fen by David Rudkin

• David Rudkin on Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr