Myrna Loy, Charles Starrett and Boris Karloff.

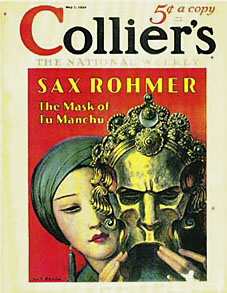

Los Alamos ranch school where they later made the atom bomb and couldn’t wait to drop it on the yellow peril. The boys are sittin’ on logs and rocks eating some sort of food there’s a stream at the end of a slope. The counsellor was a southerner with a politician’s look about him. He told us stories by the camp fire culled from the racist garbage of the insidious Sax Rohmer. “East is evil, west is good.”

William Burroughs

More pulp, and yes, it’s still racist garbage but Charles Brabin’s 1932 film which stars Boris Karloff as Sax Rohmer’s Oriental super-villain has its pleasures if you look past the severely dated attitudes. Together with The Black Cat (1934), where Boris plays a Satan-worshipping Modernist architect (!), this is one of the best non-Frankenstein Karloff films of the 1930s, as I was reminded this weekend when re-watching it along with several Sherlock Holmes episodes.

Christopher Lee is elegantly diabolical in the later Fu Manchu films but their cheap budgets force him to skulk around in dismal underground lairs. Karloff’s Doctor has a lavish Art Deco pad whose huge rooms are furnished with a noisy Van de Graaff generator and other scientific apparatus, plus a series of torture rooms where his guests may endure death by encroaching spikes (the “Slim Silver Fingers”), being lowered into an alligator pit, or driven mad by the incessant tolling of a giant bell. I happened to notice that the Doctor’s throne is quite possibly the same one (with a fresh coat of paint) as was used a decade earlier by a notoriously unclad Betty Blythe in The Queen of Sheba (1921), a lavish silent epic which is now unfortunately lost.

Betty Blythe as the Queen of Sheba.

The flaunting of Ms. Blythe’s breasts were one of the many occurrences which led to Hollywood’s adoption of the Hays Code in the 1930s, although the Code’s full effects weren’t felt until later in the decade. The notable scene in The Mask of Fu Manchu where hunk Charles Starrett appears strapped to a table dressed in nothing but a skimpy loin cloth (having previously been thrashed by Fu’s lustful daughter) would have been toned down considerably had the film been made a few years later. All the more reason to watch it today, such scenes only add to the fun.

The Doctor prepares to inject his captive with a serum which will turn the man into a compliant slave.

• The Mask of Fu Manchu | A page about the original serial, the subsequent novel and its illustrators.

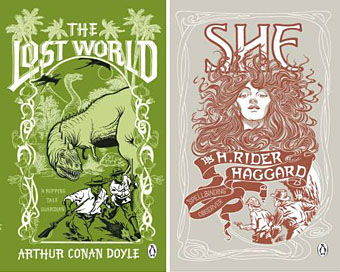

Previously on { feuilleton }

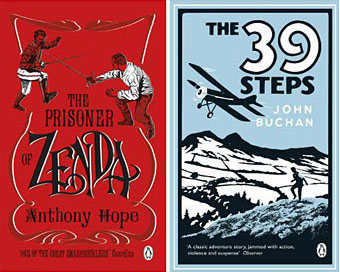

• Wladyslaw Benda