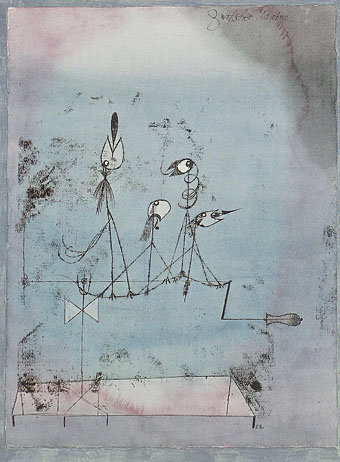

The Twittering Machine (1922) by Paul Klee.

• “Thinking of ‘writer Twitter’ as more important than writers themselves is an insult to the profession. People have been trading words for money for thousands of years. They will continue to do so after the death of a platform built on manufactured outrage, social hierarchy, unfunny jokes, stale memes, pornography, and spam. I mention this Atlantic essay only because it echoes what so many people are saying in the ether right now, not to pick on its author. The piece reads like a parody of how writers overestimate the importance of Twitter to their work and careers. It’s frankly a little embarrassing. Your work is the product you sell! Not the shitty jokes you tell with people you want to impress.” Freddie deBoer on the kerfuffle du jour. For “writer” see also “artist” or anyone else working at the intersection between commerce and creativity. From what I’ve read this week about potential technical problems at the pestilential birdcage I’d be less sanguine about its immediate survival. Since I retreated from the place as an active user two-and-a-half years ago all I get from it is the inflated subscriber number you see on the right-hand side of this page, a combination of Twitter followers plus email subscribers. The latter currently stand at some 270 individuals so if you’re among that number you can consider yourself part of a more exclusive group. And thanks for subscribing!

• “…the books of the past, besides adding to our understanding, offer something we also need: repose, refreshment and renewal. They help us keep going through dark times, they lift our spirits, they comfort us. Which means that I also strongly agree with the poet John Ashbery, who once wrote, ‘I am aware of the pejorative associations of the word “escapist,” but I insist that we need all the escapism we can get and even that isn’t going to be enough.'” Michael Dirda makes a case for reading classic, unusual and neglected books. Kudos for the mention of Anthony Skene‘s Monsieur Zenith, a character few of Dirda’s readers will have heard of.

• “While Haeckel’s paintings turn the floating phantoms into baroque spectacles of colour and flowing form, Mayer’s medusae are more sober, their tentacles subdued, their umbellate bells transparent.” Kevin Dann on the jellyfish and other “floating phantoms” described in AG Mayer’s Medusae of the World (1910).

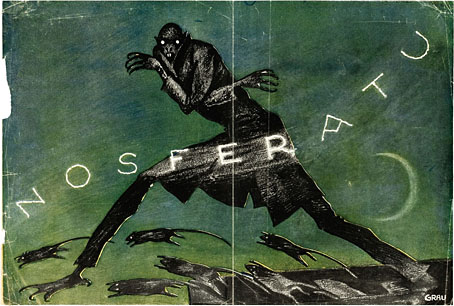

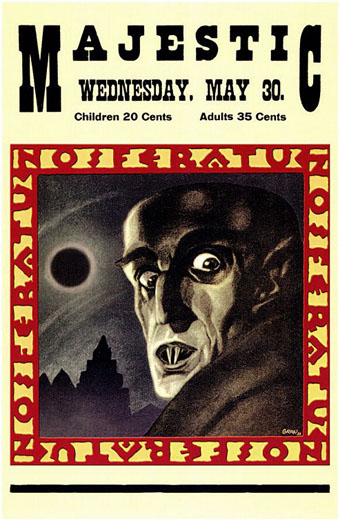

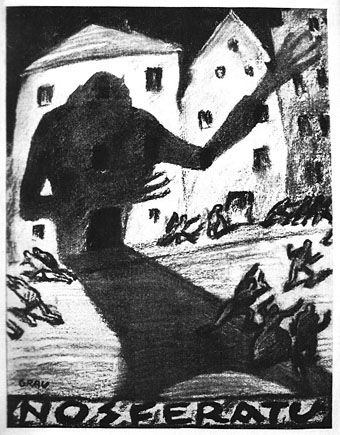

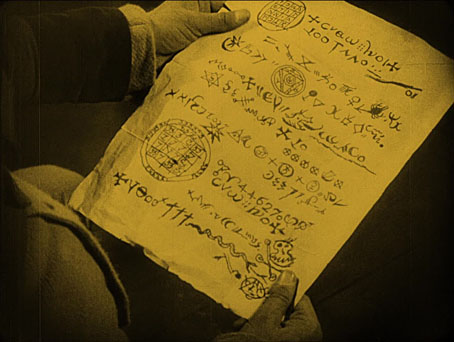

• “The passing of time has added potency to the images, giving this interpretation of the Dracula story the feel of a distant fairy tale, a myth emerging from the mists of time, erupting across the world of cinema, its shadow reaching everywhere.” Martyn Bamber on 100 years of Murnau’s Nosferatu.

• At AnOther: Camille Vivier talks about shooting nude models in the treasure-filled home of HR Giger.

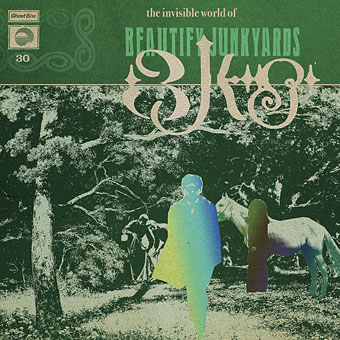

• New music: In Concert & In Residence by Sarah Davachi, and Anglo-Saxon Androids by Moon Wiring Club.

• At Spoon & Tamago: Kimono portraits were popular souvenirs for sailors visiting Japan in the 1800s.

• Mix of the week: Saturnalia: Deep Jazz for Long Nights, 1969–1980 at Aquarium Drunkard.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Clouds.

• Dark Clouds With Silver Linings (1961) by Sun Ra | Obscured By Clouds (1972) by Pink Floyd | Firmament (Cloudscape) (1995) by Main