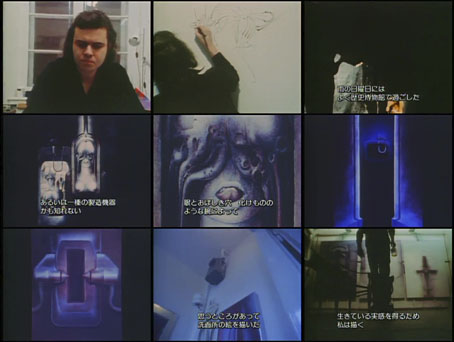

HR Giger’s art books were always very thorough in detailing all the media manifestations of the artist’s work, including film and television appearances. For years this presented tantalising questions, especially regarding the lengthy pre-Alien documentaries that were listed there: what were these films, and when would we get to see them? Giger’s Necronomicon (1976) did finally appear on YouTube a few years ago, and now here’s the second of the pair thanks to an upload of what appears to be a Japanese laserdisc.

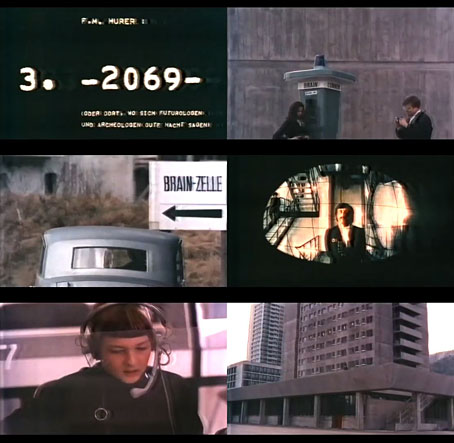

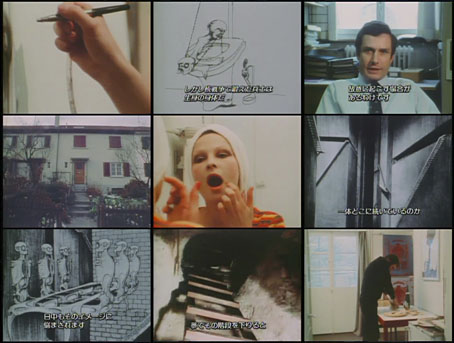

Passagen was made in 1972 by Giger’s friend Fredi M. Murer, their third film collaboration after Heimkiller and High (1967) and Swiss Made 2069 (1968). The latter (which Giger co-directed) is still frustratingly absent from the web, and similarly tantalising for being a 45-minute piece of underground science fiction which features Giger’s first production designs for cinema. Passagen was less ambitious, a 50-minute documentary about Giger’s work made for the German TV station, WDR. As a documentary it functions as a companion to Giger’s Necronomicon, while both films complement the subsequent art books, especially Giger’s Necronomicon (the book) which features many of the paintings seen in the films, together with anecdotes about their origins and inspiration. One of these anecdotes, about the nightmares induced in the young Hans Rudi by a stairway in the hotel next door to the Giger family home, is recounted in Passagen alongside the vertiginous drawings the nightmares inspired. It’s impossible to consider this piece of child psychology, and to watch the artist walking up and down stairs and stepladders, without recalling that Giger died after falling down a flight of stairs in 2014.

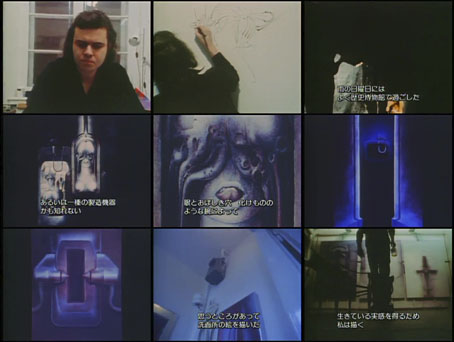

Giger’s Necronomicon is the more interesting of the two documentaries, especially now that the life and work is so well known; the art is taken more for granted, and we also get to see Giger at work on one of his big airbrush paintings. Passagen spends much of its time attempting to contextualise Giger’s drawings and paintings for an unwitting television audience, so a great deal of the running time is given over to newsreel footage of wars, riots, terrorism, atomic explosions and so on. A geneticist discusses the effects of atomic mutation while Giger’s earliest series of pictures, Atomkinder, is shown; psychoanalysts examine his paintings from a psychosexual angle.

Of more interest for Giger aficionados is the presence of his partner at the time, Li Tobler, the subject of several memorable portraits from this period. Among the working shots, the best shows Giger improvising a drawing with the same speed as Philippe Druillet in the Ô Sidarta film. Giger only started using an airbrush in 1972 so most of the works seen here are either early drawings or the paintings in the Passagen and Alptraum series, the style and colouring of which is much closer to the art world of 1972 than anything which would follow. For me the greatest revelation comes early on when Giger picks out a record to play while he’s working. The disc he chooses is just identifiable as Universal Consciousness by Alice Coltrane, an album which had been released the year before. (This isn’t the music heard on the soundtrack, however.) Alice Coltrane’s brand of ecstatic, pan-religious jazz would seem remote from Giger’s own universe but the choice isn’t so surprising if you know that he’d been a jazz enthusiast since the 1950s; in The Book of Alien (1979) his list of influences includes HP Lovecraft, John Coltrane and Miles Davis.

As is evident from the screen grabs, the film is hard-coded throughout with Japanese subtitles. Unlike Giger’s Necronomicon there’s no English overdub either, the soundtrack is in German throughout. I can’t complain when I’ve been waiting so long to be able to see this at all. For those who watched the later film divided into four YouTube clips there’s now a complete version (also Japanese but with English overdub) here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Heimkiller and High

• The Man Who Paints Monsters In The Night

• Hans by Sibylle

• HR Giger album covers

• Giger’s Necronomicon

• Dan O’Bannon, 1946–2009

• Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune

• The monstrous tome