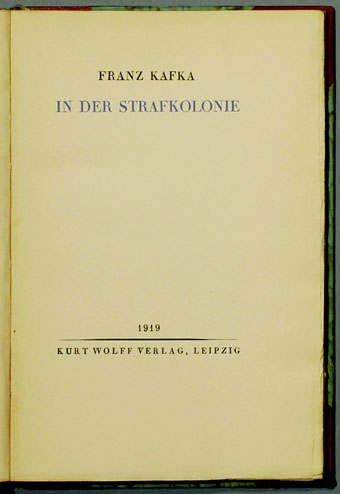

• In der Strafkolonie (In the Penal Colony, 1919), a short story by Franz Kafka

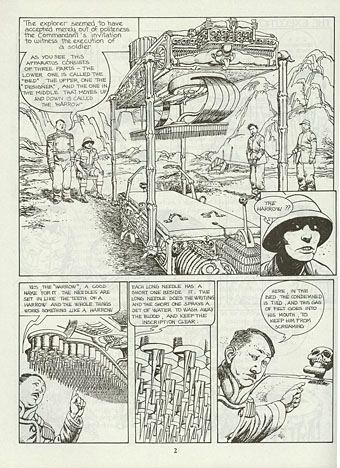

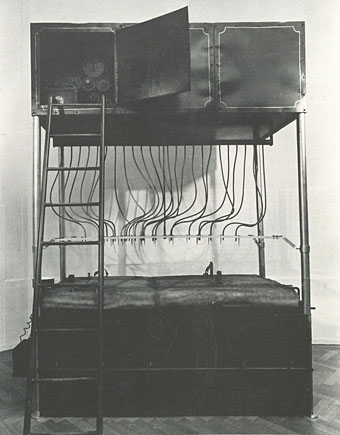

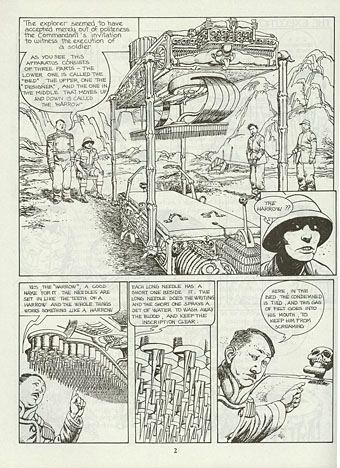

“Yes, the harrow,” said the Officer. “The name fits. The needles are arranged as in a harrow, and the whole thing is driven like a harrow, although it stays in one place and is, in principle, much more artistic. You’ll understand in a moment. The condemned is laid out here on the bed. First, I’ll describe the apparatus and only then let the procedure go to work. That way you’ll be able to follow it better. Also a sprocket in the inscriber is excessively worn. It really squeaks. When it’s in motion one can hardly make oneself understood. Unfortunately replacement parts are difficult to come by in this place. So, here is the bed, as I said. The whole thing is completely covered with a layer of cotton wool, the purpose of which you’ll find out in a moment. The condemned man is laid out on his stomach on the cotton wool—naked, of course. There are straps for the hands here, for the feet here, and for the throat here, to tie him in securely. At the head of the bed here, where the man, as I have mentioned, first lies face down, is this small protruding lump of felt, which can easily be adjusted so that it presses right into the man’s mouth. Its purpose is to prevent him screaming and biting his tongue to pieces. Of course, the man has to let the felt in his mouth—otherwise the straps around his throat would break his neck.” “That’s cotton wool?” asked the Traveler and bent down. “Yes, it is,” said the Officer smiling, “feel it for yourself.”

He took the Traveler’s hand and led him over to the bed. “It’s a specially prepared cotton wool. That’s why it looks so unrecognizable. I’ll get around to mentioning its purpose in a moment.” The Traveler was already being won over a little to the apparatus. With his hand over his eyes to protect them from the sun, he looked at the apparatus in the hole. It was a massive construction. The bed and the inscriber were the same size and looked like two dark chests. The inscriber was set about two metres above the bed, and the two were joined together at the corners by four brass rods, which almost reflected the sun. The harrow hung between the chests on a band of steel.

The Officer had hardly noticed the earlier indifference of the Traveler, but he did have a sense now of how the latter’s interest was being aroused for the first time. So he paused in his explanation in order to allow the Traveler time to observe the apparatus undisturbed. The Condemned Man imitated the Traveler, but since he could not put his hand over his eyes, he blinked upward with his eyes uncovered.

“So now the man is lying down,” said the Traveler. He leaned back in his chair and crossed his legs.

“Yes,” said the Officer, pushing his cap back a little and running his hand over his hot face. “Now, listen. Both the bed and the inscriber have their own electric batteries. The bed needs them for itself, and the inscriber for the harrow. As soon as the man is strapped in securely, the bed is set in motion. It quivers with tiny, very rapid oscillations from side to side and up and down simultaneously. You will have seen similar devices in mental hospitals. Only with our bed all movements are precisely calibrated, for they must be meticulously coordinated with the movements of the harrow. But it’s the harrow which has the job of actually carrying out the sentence.”

(Translation by Ian Johnston)

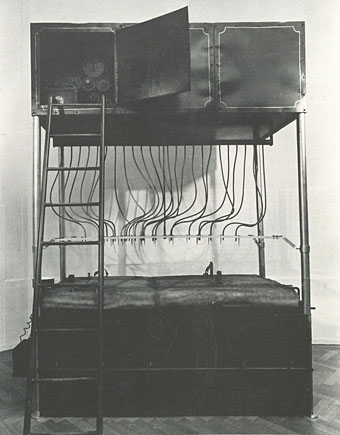

• An authorless construction for The Bachelor Machines, 1975–77, an exhibition curated by by Harald Szeemann

• Kafka: The Execution (1989), a comic strip by Leopoldo Duranona

Read the full strip.

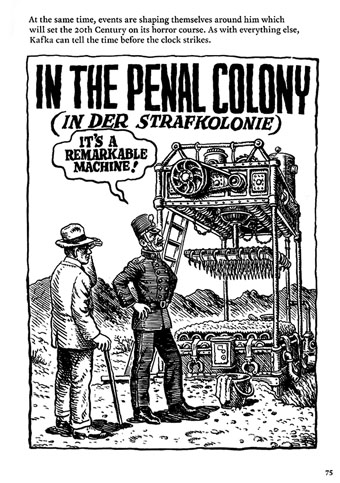

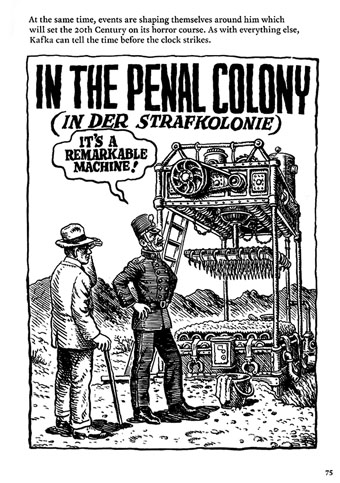

• A page from Introducing Kafka (1993), an illustrated biography of Franz Kafka by David Zane Mairowitz and Robert Crumb

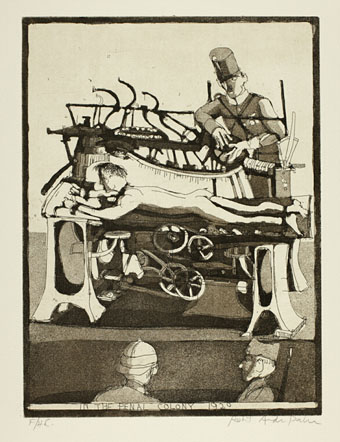

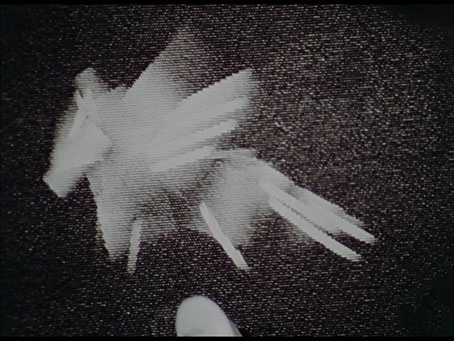

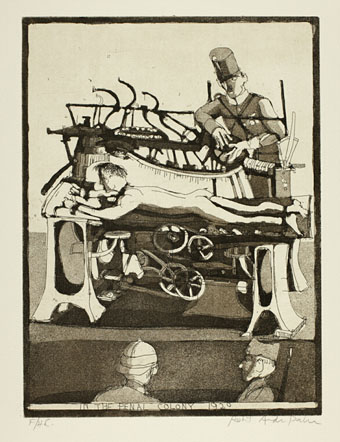

• In the Penal Colony, 1920, from Franz Kafka: Dreams, Diaries, and Fragments (1994), a print by Robert Andrew Parker

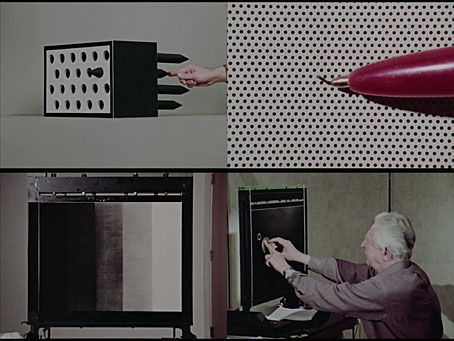

• Zoetrope (1999), a short film by Charlie Deaux

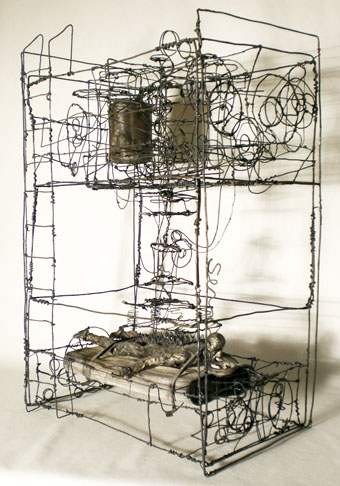

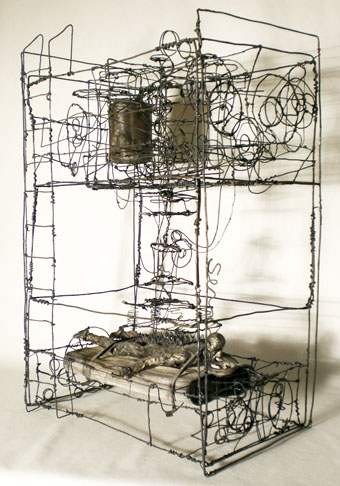

• Franz Kafka: The Peculiar Apparatus from the Story In the Penal Colony (undated), a sculpture by Martin Senn

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Metamorphosis of Mr Samsa, a film by Caroline Leaf

• Kafkaesque

• Screening Kafka

• Designs on Kafka

• Kafka’s porn unveiled

• A postcard from Doctor Kafka

• Steven Soderbergh’s Kafka

• Kafka and Kupka