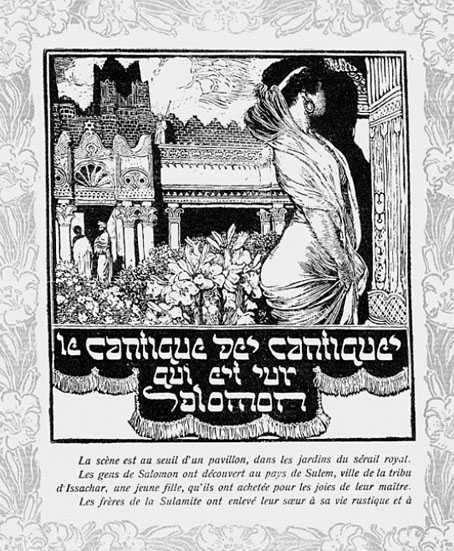

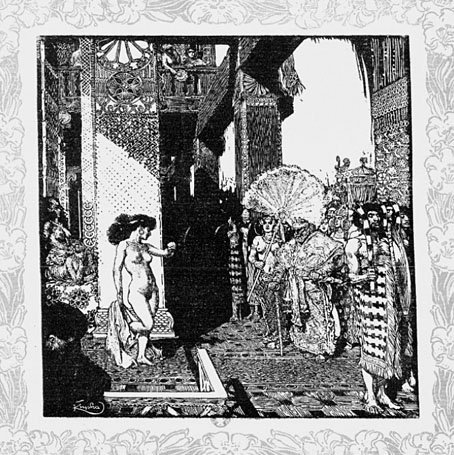

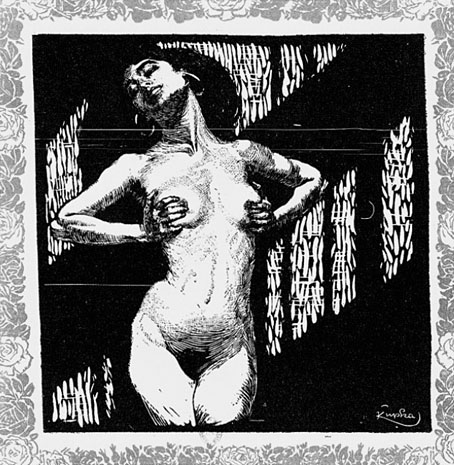

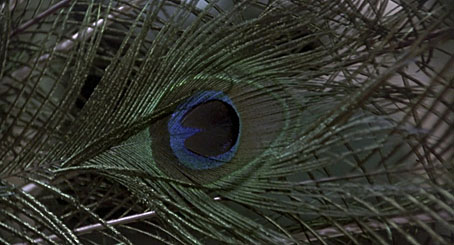

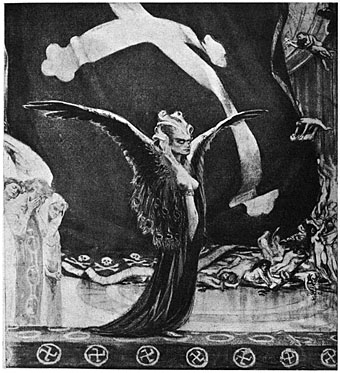

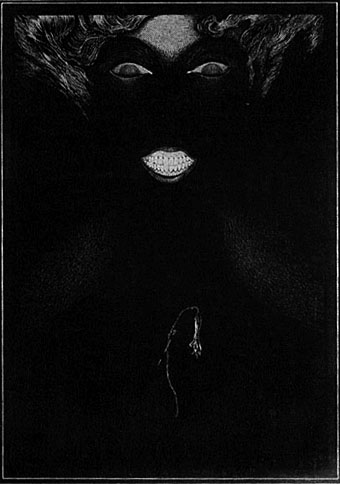

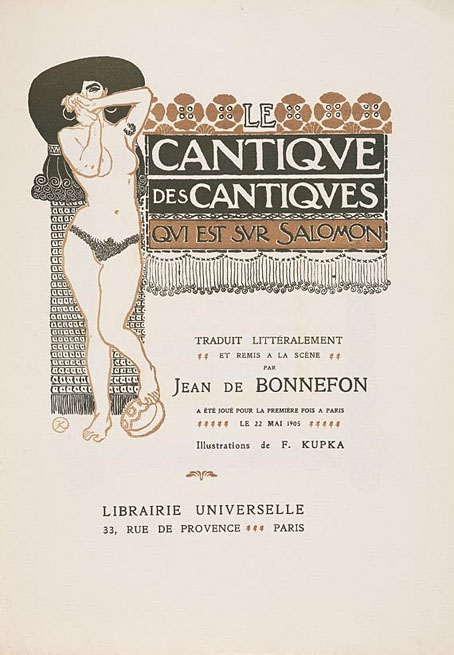

An oddity from the career of František Kupka, Le Cantique des Cantiques (1905) in this version is a stage presentation of the Song of Solomon by Jean de Bonnefon. Kupka provided a series of illustrations in a style similar to his Symbolist paintings which in the original printing are decorated with coloured borders. The copies here are from a bad scan at Gallica whose page I’ve been unable to find again. For the moment there are better copies to be seen at eBay. The drama is very much oriented towards the sexual exotica which Oscar Wilde had rendered notorious in Salomé, and which underpins so many of the obsessions of the period. A few years after this Kupka was in a different world entirely, following new directions into abstract art.