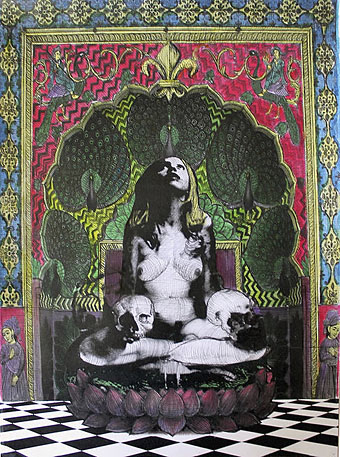

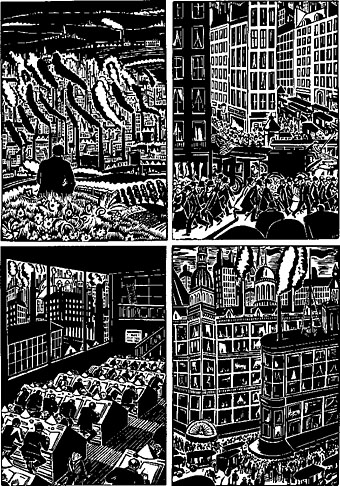

Having mentioned Frans Masereel in the previous post, here’s a short animated film based on one of Masereel’s wordless novels. Masereel’s The Idea (1920) concerns the birth and progress of radical thought in an illiberal society, with the troublesome conception embodied as a naked woman. When the idea escapes into the world the authorities try to cover her nakedness, but their efforts fail to prevent her image being disseminated by the printing press…

Berthold Bartosch was a Czech animator whose 25-minute adaptation of the book was released in 1932. Frans Masereel helped with the creation of the film in its early stages but he lost his patience with the slow pace of the animation process. Bartosch’s film is significant for being one of the first animated dramas to aim self-consciously at art rather than comedy or entertainment for children. Also significant is the score by Arthur Honegger whose use of the ondes Martenot is claimed as the first use of an electronic instrument for cinematic purposes. Bartosch’s animation technique brings to life cut-out figures in nebulous, layered compositions that anticipate the films that Yuri Norstein would be making decades later. It’s a shame that all the online copies of the film are so poor, it ought to be seen in better quality. Watch it here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Destiny, A Novel in Pictures by Otto Nückel

• Crime and Punishment, a film by Piotr Dumala

• Walls, a film by Piotr Dumala

• The Nose, a film by Alexandre Alexeieff & Claire Parker

• Yuri Norstein animations

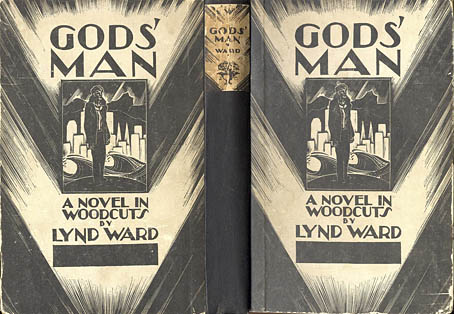

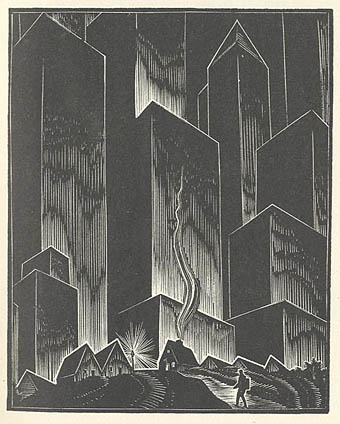

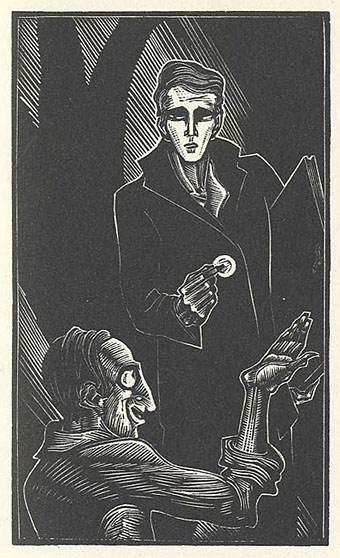

• Gods’ Man by Lynd Ward

• Frans Masereel’s city