It’s the tragedy of theatre that its nature as a medium dependent on performance leaves so little record of its works behind. But there is one major film of the Living Theatre at its most provocative and it’s fitting that this should appear on a new DVD from Arthur Magazine in the year of the company’s sixtieth anniversary.

NEW FROM ARTHUR: PARADISE NOW: THE LIVING THEATRE IN AMERIKA DVD. LIMITED EDITION OF 1,000 – PRE-ORDER NOW – SHIPS OCT 1ST, 2007!

the screams

the unchained soarings of a sincerity which is on its way

to this revolution of the whole body without which nothing can

be changed. – Antonin Artaud

Arthur Magazine proudly presents our newest release PARADISE NOW: The Living Theatre in Amerika DVD featuring rare, never-before-distributed films and a bacchanal of revolutionary multimedia documents from The Living Theatre’s historic and influential ’68–’69 American tour. A fulminating art-meets-life installation brought to you in collaboration with The Living Theatre, The Ira Cohen Akashic Project and Saturnalia Media Rites of the Dreamweapon.

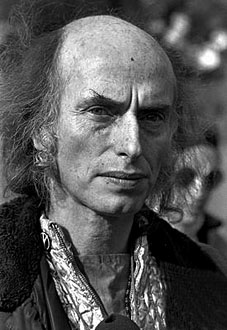

DVD INCLUDES – PARADISE NOW: The Living Theatre in Amerika (1969) a film by Marty Topp, produced by Ira Cohen for Universal Mutant

• EMERGENCY (1968) a film by Gwen Brown, featuring precious footage of Living Theatre productions Mysteries and smaller pieces, Paradise Now, and Frankenstein

• RARE PHOTOGRAPHS of Paradise Now at Brooklyn Academy of Music by Don Snyder

• THE MAP OF PARADISE NOW, a 14″ x 19″ double-sided, commemorative poster + ‘zine including texts by Antonin Artaud, Julian Beck, Judith Malina, Ira Cohen and Don Snyder

ADDITIONAL SPECIAL FEATURES

• Slideshow / Installation, The full theatrical script

• Paradise Now: A Collective Creation of The Living Theatre as written down by Julian Beck and Judith Malina

• Video Interviews with director Judith Malina, Hanon Reznikov, Steve Ben Israel, and producer Ira Cohen

• The Spinning Wheel by Steve Ben Israel, soundtrack to EMERGENCY sourced from agit-prop radio broadcasts

• Akashic Video Gallery of excerpts from current and forthcoming Arthur DVD releases

WHAT IS PARADISE NOW?

In 1968 The Living Theatre, led by Julian Beck and Judith Malina, triumphantly returned to America from years of self-imposed exile in Europe with their theatrical breakthrough Paradise Now. The play introduces the practice of collective creation, dissolving the boundaries of human interactions and forging a harmony between the actors and audience. Of this process, Julian Beck writes, “Collective creation is the secret weapon of the people… This play is a voyage from the many to the one and from the one to the many. It’s a spiritual voyage and a political voyage, a voyage for the actors and the spectators. The play is a vertical ascent toward permanent revolution, leading to revolutionary action here and now. The revolution of which the play speaks is the beautiful, non-violent, anarchist revolution.The purpose of the play is to lead to a state of being in which non-violent revolutionary action is possible.”

The result of this shared voyage is the spontaneous creation of a temporary anarchist collective – free from the enslavements of war, violence, the State, money and the self.

CRITICAL PRAISE FOR PARADISE NOW

“Marty Topp’s beautiful film of Paradise Now reveals how the theories of revolutionary change and the experience of sexual liberation are not separate paths to the beautiful nonviolent anarchist revolution. Practiced together they are a single thrust, encompassing both political action and sensual joy, leading to the dreamed-of terrestrial paradise.” Judith Malina

“Paradise Now is possibly The Living Theatre’s greatest achievement – unsurpassable!” Ira Cohen

“This past spring, in a group art show at New York?s Swiss Institute, an old black-and-white television played a grainy print of bodies writhing to the tune of distant drumming. “As long as you have people working for money and not love, there will be violence,” intoned a tall, angular man on the screen. The bodies – women in scant bikinis and men in what looked like loincloths-piled together in an orgiastic tribal dance, some simulating (or perhaps actually having) sex as the voice continued: “Psycho-sexual repression is impeding the revolution.” What looked like an underworld-of the 1960’s counter-cultural variety, in this case- is the Living Theatre?s Paradise Now, as documented in the 1969 Ira Cohen-produced film Paradise Now: The Living Theatre in Amerika ? soon to be released on DVD from Arthur Magazine.” CAN THEATER STAGE A REVOLUTION – Traci Parks, Fall ’07 Preview, V MAGAZINE

“Joyous, brutal, exploding with the kinetic energies of psychic catharsis… Marty Topp’s PARADISE NOW: The Living Theatre in Amerika has captured the essence of this extraordinary theatrical experiment. It is unquestionably one of the finest artistic documentaries to come out of the United States cinema. Its heartfelt sincerity should be sheer inspiration to the many young people throughout the country who are struggling to make meaningful and influential work. It is the reverberation of a crucially important message that must not be neglected, for the consequences are too terrible to endure.

“Marty Topp’s achievement is not just in the making of a great film, but in making us remember again, Paradise as a reality.” PARADISE ON FILM – Don Snyder, July 1970, East Village Other

“Like an astonishing portion of the country’s popular music, the spectacles of The Living Theater proved to be in content and form outside the social system – not structured by it nor, except as outlet, implementing it: liberated territory.” Revolution at the Brooklyn Academy – Stefan Brecht, The Drama Review number 43: Spring 1969, The Living Theater Issue