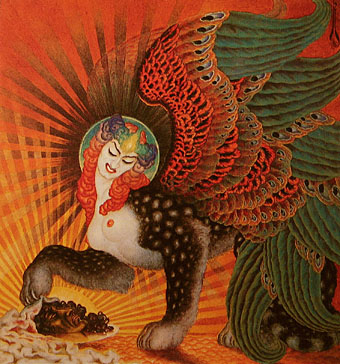

Ermitaño Meditando (1955) by Remedios Varo.

• Public Domain Review announces the Public Domain Image Archive. I’ve added it to the list. Meanwhile, the PDR regular postings include Francis Picabia’s 391 magazine (1917–1924).

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: The Well at the World’s End by William Morris.

• At Smithsonian Magazine: “See 25 incredible images from the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Contest”.

The ideas are more complex than the presentation suggests, but not vastly. Neither is it exactly breaking new ground. Art is everywhere, they say, from fingernails to fine dining; art is not a message to be decoded, but takes on new meanings in the mind of each viewer; art allows us to experience emotions in a “safe” context, like a form of affective practice; art helps us to imagine new worlds, thereby expanding the boundaries of what’s possible in the real world. The point isn’t to be original, though, but to distil a lifetime’s worth of practical wisdom and reflection. The result is a kind of joyous manifesto: just the thing to inspire a teenager (or adult) into a new creative phase. Eno and Adriaanse conclude with a “Wish”: that the book helps us understand that “what we need is already inside us”, and that “art – playing and feeling – is a way of discovering it”.

Brian Eno and Bette Adriaanse talking to David Shariatmadari about their new book, What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory

• “Crunchie: The Taste Bomb!” DJ Food unearths four psychedelic posters promoting Fry’s Crunchie bars.

• New music: Music For Alien Temples by Various Artists, and Awakening The Ancestors by Nomad Tree.

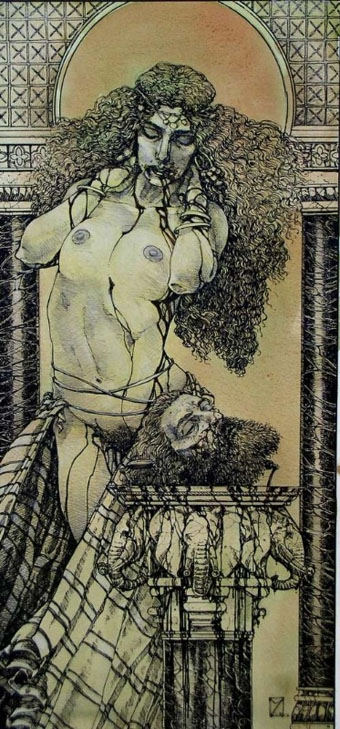

• At Wormwoodiana: Mark Valentine lays out a history of the Tarot in England.

• Sun Ra & His Intergalactic Research Arkestra live on German TV, 1970.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Chris Marker Day (restored/expanded).

• At the BFI: Anton Bitel on 10 great Mexican horror films.

• Matt Berry’s favourite albums.

• Tarot (Ace of Wands Theme) (1970) by Andrew Bown | Tarotplane (1971) by Captain Beefheart And His Magic Band | Tarot One (2012) by Tarot Twilight