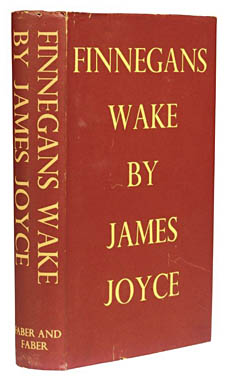

The Guardian‘s archive feature today has their original review of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce.

Who, it may be asked, was Finnegan?

Friday May 12, 1939

Mr Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, (Faber, 25s), parts of which have been published as “Work in Progress” does not admit of review. In twenty years’ time, with sufficient study and with the aid of the commentary that will doubtless arise, one might be ready for an attempt to appraise it.

The work is not written in English, or in any other language, as language is commonly known. I can detect words made up out of some eight or nine languages, but this must be only a part of the equipment employed. This polyglot element is only a minor difficulty, for Mr Joyce is using language in a new way: “Margaritomancy! Hyacinthous pervinciveness! Flowers. A cloud. But Bruto and Cassio are ware only of trifid tongues the whispered wilfulness (’tis demonal!) and shadows shadows multiplicating.”

The easiest way to deal with the book would be to become “clever” and satirical or to write off Mr Joyce’s latest volume as the work of a charlatan. But the author of Dubliners, A Portrait of an Artist and Ulysses is obviously not a charlatan, but an artist of very considerable proportions. I prefer to suspend judgement. What he is attempting, I imagine, is to employ language as a new medium, breaking down all grammatical usages, all time space values, all ordinary conceptions of context. Compared with this, Ulysses is a first-form primer.

What, it may be asked, is the book about? That, I imagine, is a question which Mr Joyce would not admit. This book is nothing apart from its form, and one might as easily describe in words the theme of a Beethoven symphony.

The clearest object in time in the book is the Liffey, Anna Livia, Dublin’s legendary stream, and the most continuous character is HC Earwicker, “Here Comes Everybody”: the Liffey as the moment in time and space, and everything, everybody, all time as the terms of reference, back to Adam or Humpty Dumpty, but never away from Dublin.

This seems the suggestion of the musical half-sentence with which the work begins: “Riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

Who, it may be asked, was Finnegan? But I gather that there is an Irish story of a contractor who fell and was stretched out for dead. When his friends toasted him he rose at the word “whiskey” and drank with them. In a book where all is considered, this legend, too, has its relevance.

B Ifor Evans