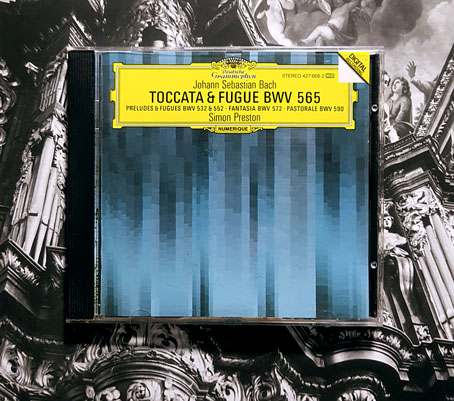

The theme in question.

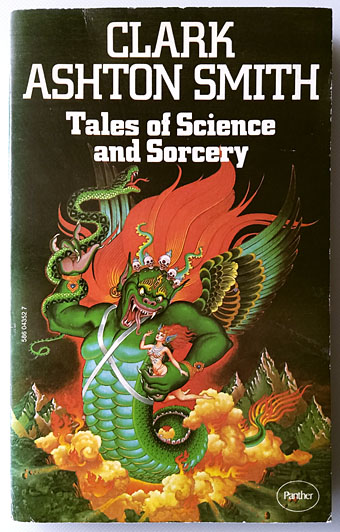

When did the first few bars of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor BWV 565 become a signifier of an unhinged personality, and thereby a horror cliché? The question was raised by my film viewing in the run-up to Halloween following a return visit to The Black Cat, Edgar G. Ulmer’s Universal oddity. Ulmer’s film is the best of a trio of Universal horrors packaged by Eureka in a double-disc set, part of the company’s ongoing programme to reissue obscure films starring Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. The three films in the set—Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), The Black Cat (1934) and The Raven (1935)—all star Lugosi, with Karloff co-starring in The Black Cat and The Raven. The Bach piece was impossible to ignore after watching all three films together. In The Black Cat we see a villainous Karloff regaling a potential victim with a performance of Toccata and Fugue on his home organ. Bela Lugosi does the same in The Raven, where he portrays an equally villainous but much more demented doctor obsessed with the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. The Universal horror films have been the source of many cinematic clichés of which this is a further example, even if the use of Toccata and Fugue to signify villainy or madness predates The Black Cat.

Wikipedia’s incomplete list of the composition’s cinematic appearances states that Toccata and Fugue was already a theatrical cliché by the early 1930s but offers no evidence for the claim. It’s likely there were silent films using the piece for their scores when so much silent orchestration borrows from pre-existing classical music. But silent films, today as in the past, can be scored in many different ways, the score isn’t always permanently attached to the film. The one silent film that you might expect to use the Bach piece, the 1925 version of The Phantom of the Opera, has a fine score by Carl Davis in its restored form, but no Toccata and Fugue. A brief history of the cinematic life of the piece would go something like this…

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931)

Rouben Mamoulian’s excellent adaptation opens with a view through the eyes of Dr Jekyll (Frederic March) playing another Bach piece on the organ; prior to this the film’s titles had been scored with an orchestral arrangement of Toccata and Fugue. An hour later the composition returns when Jekyll plays an extract from the fugue section, an ominous sign despite his joy at his impending marriage.

The Black Cat (1934)

Despite the title, this one has nothing at all to do with Edgar Allan Poe. Instead of another spurious adaptation we get Boris Karloff as Hjalmar Poelzig, cinema’s only Satanist architect. The character is a bizarre amalgam of Aleister Crowley and Hans Poelzig, a German architect who designed the sets for Paul Wegener’s third and best Golem film.

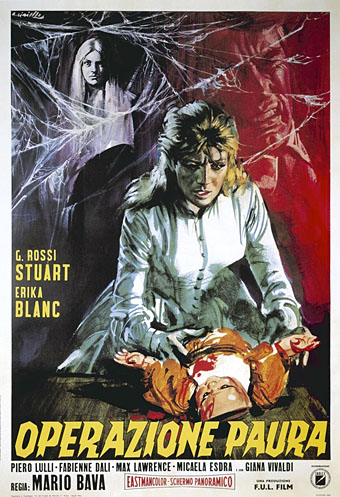

The Raven (1935)

This one does at least contain a number of Poe references. Lugosi is a brilliant doctor who also happens to be a homicidal maniac, his Poe obsession having led him to fill the secret rooms in his house with torture devices.

A Canterbury Tale (1944)

Not a horror film but included here because Powell & Pressburger’s war-time drama is about the last time you find the Bach piece being used in an unironic manner, intended to evoke religious awe rather than madness or doom. Prior to this the piece had also been used to soundtrack an abstract animation by Mary Ellen Bute, Synchromy No. 4: Escape (1938), two years before Disney did something very similar in Fantasia. In A Canterbury Tale Dennis Price is a conscripted cinema organist finally arrived at Canterbury Cathedral prior to being shipped to the front. Before he leaves, the cathedral organist allows him to play the music for the departure service which in turn allows us to hear Bach’s piece illustrating views of genuine Gothic grandeur.

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Its fitting that the self-conscious use of Toccata and Fugue begins with a supremely self-conscious film. Billy Wilder’s masterpiece isn’t a horror film either but it is a full-blown Gothic drama, being narrated by a dead man whose first encounter with the mentally fragile Norma Desmond sees him being mistaken for an undertaker. The Bach piece is played by Desmond’s butler, Max, a washed-up film director portrayed by a genuine (and genuinely great) washed-up film director, Erich von Stroheim. Max may not be a maniac but his employer (and ex-wife) is certainly unhinged, while Stroheim himself was notorious in his directing days for his megalomania, overspending lavishly and refusing to compromise with the studios over the editing of his films. (The first cut of his mutilated epic, Greed, ran over nine hours.) Since the 1925 Phantom of the Opera was mentioned earlier, it’s worth noting that Norma Desmond’s boat-shaped bed is the same prop that appears in the silent Phantom’s underground lair.