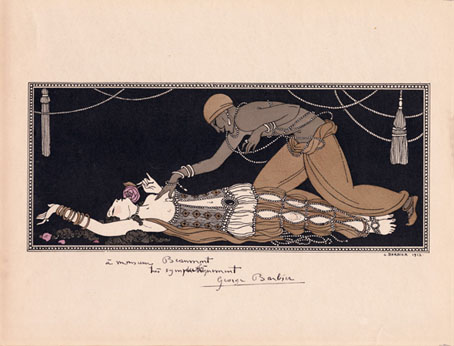

Ida Rubinstein as Zobeide and Vaslav Nijinsky as the Golden Slave in Schéhérazade (1913) by George Barbier.

Another great exhibition at the V&A, London, Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes gathers a wealth of costumes, stage designs, photographs and ephemera—including some of Stravinsky’s manuscripts—to present a history of the legendary ballet company and their visionary impresario. For those who can’t get to London the museum website shows some of the items which will be on display, and there’s also a blog about the installing of the exhibition. The enormous frontcloth from 1924 based on Picasso’s Two Women Running on the Beach received a flurry of attention in the press here but my own attention was caught by the picture of Natalia Goncharova‘s even more enormous backcloth for The Firebird. The exhibition runs to January 9, 2011.

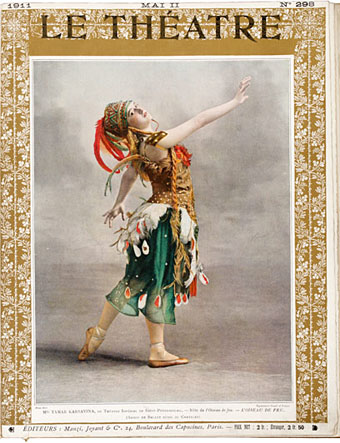

Cover of Le Théatre showing Tamara Karsavina in costume as the Firebird, May 1911.

While we’re on the subject, a new biography of the impresario, Diaghilev: A Life by Sjeng Scheijen, was reviewed last week in the New York Times:

Diaghilev loved beautiful young men, and at a time when the fashion in ballet was to exchange patronage for sex, his company provided a bounty. Scheijen dexterously plays his sources against one another to examine the erotic and professional dynamics between Diaghilev and his stars.

For a fictional (and necessarily heterosexual) account of those erotic and professional dynamics, I recommend Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) which not only has a central character based on Diaghilev but includes among the cast of real dancers Léonide Massine, dancer and principal choreographer of the Ballets Russes from 1915 to 1921.

See also:

• Russian Ballet History | An archive and documentary site.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Pamela Colman Smith’s Russian Ballet

• The art of Ivan Bilibin, 1876–1942

• Jack Cardiff, 1914–2009

• Magic carpet ride

• Le Sacre du Printemps

• Images of Nijinsky