The Burroughs Centenary approaches, and this month sees the 30th anniversary of this Burroughs-related item. Decoder is a low-budget feature film from 1984 written by Klaus Maeck, and directed by Jürgen Muschalek (aka Muscha). Despite the constraints of budget and casting—many of the actors are amateurs—Decoder is truer to the techno-anarchist strand of Burroughs’ fiction than anything attempted before or since, and it’s arguably truer to the spirit of his works as a whole than David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch.

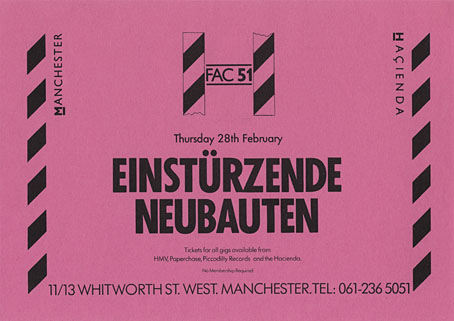

Decoder was shot in Hamburg in the early 1980s although the city is never properly identified in order to maximise the film’s near-future qualities. The narrative concerns attempts by FM (played by FM Einheit from Einstürzende Neubauten) to combat the insidious effects of muzak in burger restaurants using tapes created with his home-made electronics. William Burroughs makes a couple of brief appearances as the “Old Man” with a shop full of electronic components. Among the rest of the cast there’s Christiane Felscherinow, dividing her time between peep-show sex-work and languishing in a room filled with her pet frogs; and Genesis P-Orridge in his Psychic TV gear as the head of an underground pirate cult who encourage FM to launch an offensive against the muzak signals. Original music is provided by Dave Ball (from Soft Cell) and FM Einheit. The complete score is very good, featuring additional tracks by Soft Cell, Einstürzende Neubauten and Matt Johnson. Watched today, the narrative seems very much a product of its time, and somewhat outmoded. In 1984 home computing was increasingly prevalent, and cheap sound-sampling was just around the corner; Decoder is the last hurrah of an analogue struggle against the agents of the Control Virus.

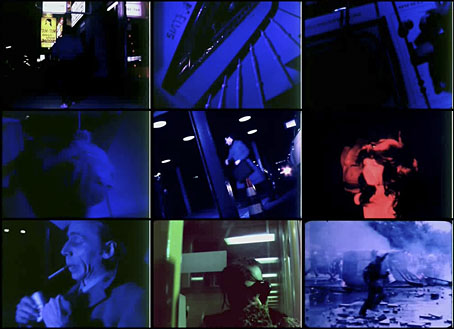

It’s a shame Jürgen Muschalek didn’t get to make anything else when he was obviously trying for some kind of cross between Burroughs’s The Electronic Revolution (1970) and Godard’s Alphaville (1965). Low-budget films often suffer visually but this one makes impressive use of vivid lighting and plenty of shadow which helps alleviate some of the weaknesses elsewhere. David Cronenberg has often acknowledged the influence of avant-garde types such as Burroughs and Warhol but his own films tend to be very conservative in their presentation. Muschalek at least tries to parallel some of Burroughs’ fragmented narrative techniques with an abrupt and disjunctive editing style. The film as a whole is much more in tune with the early Industrial Culture ethos than Peter Care’s noir pastiche, Johnny YesNo, but suffered from being more read about than seen in the 1980s. A few copies can be found online. In 2010 it finally appeared on DVD with extra material and a soundtrack disc.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The William Burroughs archive