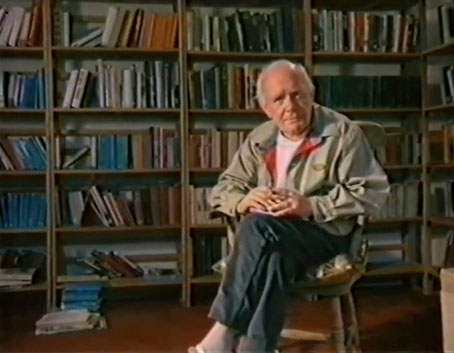

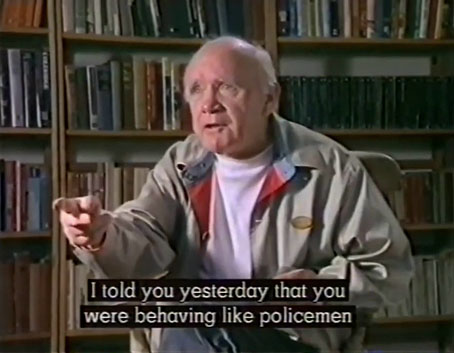

In the summer of 1985 he also gave a televised interview to the BBC. It was to be his last public statement. Genet demanded £10,000 in advance and in cash. In return he agreed to be filmed for two days in the house of Nigel Williams, a young novelist, television presenter and the translator of Deathwatch. At the time of the student uprising in May 1968, Genet had been very critical of the form the students’ debates took, especially during the occupation of the Théâtre de l’Odèon. As an experienced playwright he knew that the form is more communicative in a live or filmed event than what anyone manages to say. Accordingly, he constantly interrupted the formula of the television interview. He genuinely believed that he was no more interesting or important than the camera crew and insisted on asking the technicians questions. This reversal of the ordinary television format infuriated many viewers, but none forgot the show.

Edmund White, from Genet: A Biography (1993)

I didn’t forget the show. In fact this particular programme, Saint Genet, has been in the top five of those I wanted to see again ever since copies of old TV recordings started circulating on the internet. The film is another from the BBC’s Arena arts series, and one the corporation is proud of judging by their inclusion of clips in celebrations of Arena‘s history. This pride hasn’t extended to repeat screenings of the entire interview, however, apart from a single occasion a few weeks after Genet’s death in 1986. The days are long passed when the BBC would devote 50 minutes of its evening air-time to a writer who didn’t have a book to plug or some attachment to a popular film or TV drama. In 1985 you could expect as much while also being offered a programme that countered the reactionary tenor of the time: an author whose novels were filled with gay sex, and populated by all manner of social outcasts, from male prostitutes to thieves, murderers and the like.

Genet in later years refused to discuss his novels or plays so co-director/interviewer Nigel Williams oriented the discussion around the author’s life (many details of which informed his fiction) while augmenting this with readings from the novels along with extracts from films and plays. I didn’t remember the extracts at all even though this would have been my first glimpse of scenes from the only film that Genet directed (and which he typically disowned), Un Chant d’Amour. More memorable was the sight of Genet himself sitting there for the best part of an hour, rolling cigarettes and verbally jousting with a pair of nervous interviewers in a mood of mingled amusement and exasperation. In the past I’ve been uncharitable about Williams’ handling of the situation but he ought to be congratulated for having inadvertently given us a film that’s so typical of its subject. Genet spent most of his life biting the hand that fed him, and always chaffed at the attention he received from the educated middle classes, even though these were the people who were most interested in (and paid for) his novels and plays. Edmund White’s biography tells us that Genet was unimpressed with Williams’ home (which he compared to something out of a Miss Marple story), and was annoyed when he saw the technical crew eating at a separate table to the producers. This annoyance was translated to the second half of the interview which he described as being like a police interrogation.

In his introductory comments Williams says that this was the first interview Genet had given to a major TV network, but it wasn’t Genet’s first filmed interview. The 52-minute film made by Antoine Bourseiller in 1981 contrasts strikingly with the Arena programme, demonstrating that Genet could talk with ease and at length before a camera. The reason, as White once again explains, is that Genet had planned the film in advance with Bourseiller, selecting the topics for conversation and even helping to edit the footage later. So the difference in attitude was all about control, or the lack of it. Wresting control from the BBC meant directing the questions back at the interviewers while drawing attention to the power relations and the intimidating nature of the interview process.

All of this begs the question as to why Genet agreed to place himself in a situation that he found so uncomfortable when he could easily have refused. We’re left to guess but he certainly didn’t do it for the money; he continued to live frugally despite the international success of his literary works. Large sums such as the £10,000 he extracted from the BBC he regularly passed on to needy friends or to political groups who he felt could put the funds to better use. Whatever the reason behind Genet’s participation, I think Williams and co. would agree that their money was well spent.

Previously on { feuilleton }

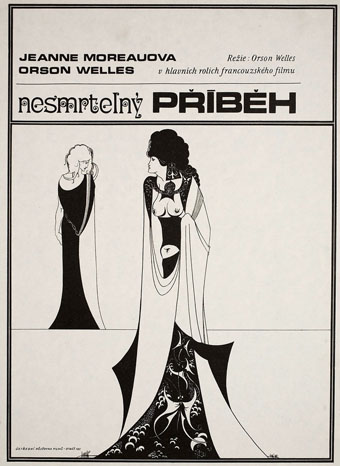

• Covering Genet

• Notre Dame des Fleurs: Variations on a Genet Classic

• Genet art

• Flowers: A Pantomime for Jean Genet

• Querelle de Brest

• Jean Genet, 1981

• Un Chant d’Amour (nouveau)

• Jean Genet… ‘The Courtesy of Objects’

• Querelle again

• Saint Genet

• Emil Cadoo

• Exterface

• Penguin Labyrinths and the Thief’s Journal

• Un Chant d’Amour by Jean Genet