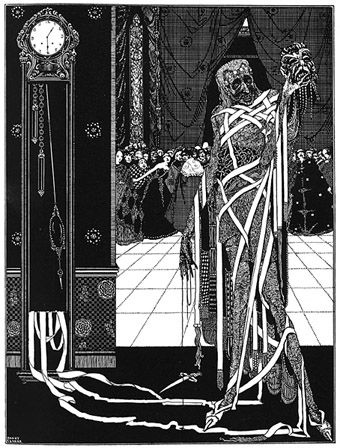

“The dagger dropped gleaming upon the sable carpet.” The Masque of the Red Death illustrated by Harry Clarke, 1919.

• 2020 is the year of enormous pink lady faces on book covers, apparently. As someone who spends little time following cover trends, the identification of a new variety of herd behaviour among designers or their art directors is always fascinating and bizarre.

• Tomoko Sauvage plays her porcelain and glass instruments inside a disused water tank in Berlin for a new album, Fischgeist. The Wire has previews.

• At The Paris Review: Craig Morgan Teicher on the later work of Dorothea Tanning, and Daniel Mendelsohn on the rings of Sebald.

Unlike many of the rapidly forgotten [Nobel] “winners”, and despite the occasional sniffy critic wondering “who still reads it?” Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet has never been out of print since he published it in 1957. The centenary of his birth in 2012 raised a flurry of revived interest in Durrell. Indeed the whole Durrell family has been popping up regularly in reprints of Lawrence’s novels and poetry, in his brother Gerald’s popular tales of his “family and other animals,” and in several TV series about their life in Greece on Corfu island in the late 1930s. A BBC interviewer once asked Lawrence about the difference between his writing and brother Gerald’s. He replied: “I write literature. My brother writes books that people read.”

I’ve read Gerald and I’ve read Lawrence; I prefer Lawrence, thank you. Thomas O’Dwyer examines the chef d’oeuvre of the elder Durrell, The Alexandria Quartet

• Dark Entries shares Patrick Cowley’s cover of Chameleon by Herbie Hancock. The original is here.

• Saunas, sex clubs and street fights: how Sunil Gupta captured global gay life.

• Inside the Grace Jones exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary.

• Rob Walker on how dub reggae’s beats conquered 70s Britain.

• Who invented the newspaper? John Boardley reports.

• Spread The Virus (1981) by Cabaret Voltaire | Cut Virus (2003) by Bill Laswell | The Unexclusive Virus ~even our invincible religion “Technology” cannnot~ (2006) by Kashiwa Daisuke