Falling out with Oscar

| John Gray, Oscar Wilde and Dorian Gray.

Tag: Dorian Gray

A TV Dante by Tom Phillips and Peter Greenaway

More cult stuff from Ubuweb, you lucky people. Being a big Tom Phillips enthusiast I’ve been watching A TV Dante (1989) for years, having taped the one and only broadcast of the series. I also bought the accompanying booklet (below).

This ambitious program, produced by the award-winning film director Peter Greenaway and internationally-known artist Tom Phillips, brings to life the first eight cantos of Dante’s Inferno. Featuring a cast that includes Sir John Gielgud as Virgil, the cantos are not conventionally dramatized. Instead, the feeling of Dante’s poem is conveyed through juxtaposed imagery that conjures up a contemporary vision of hell, and its meaning is deciphered by eminent scholars in visual sidebars who interpret Dante’s metaphors and symbolism. This program makes Dante accessible to the MTV generation. Caution to viewers: program contains nudity. (8 segments, 11 minutes each)

Given the nature of the collaboration, this can’t be compared to many other TV productions. Greenaway wasn’t staging a drama, he was using the TV screen as a flat space like a moving painting, or a series of diagrams and connected symbol systems. The division of the screen has a parallel in some of Phillips’s paintings (and his artist’s book of the Inferno) and makes use of Phillips’s familiar stencil lettering. There are actors: as mentioned above, Sir John Gielgud took the role of Virgil, with Bob Peck as Dante and Joanne Whalley-Kilmer as Beatrice. And there are recurrent motifs: triangle, concentric circles, cardiograph displays, Muybridge animations and so on. “Footnotes” were provided by a company of experts who appear in small inset panels to comment on the text while it’s being read. Phillips himself is one of the principal commentators since it was his translation being used.

Peter Greenaway’s feature films have never interested me very much, I prefer him when he’s doing things like this which probably explains why I like Prospero’s Books, his version of The Tempest; much of that film’s approach seems to have been developed from A TV Dante. It’s a shame that only eight of the Cantos were filmed in this way. There were plans to film all thirty four using other directors (with Greenaway to return at the end) but this endeavour took place at the end of the period when Channel 4 was still a haven for unusual arts projects. Regime change subsequently charted a course for the lowest common denominator. And with the two leading actors now dead it wouldn’t be possible to resume the project. In the end this doesn’t matter too much. What remains is an introduction to a perennially fascinating book and an example of how television could—if someone had the courage—ditch the clichés of drama documentary and try something genuinely new.

• The official Tom Phillips website

• The Tom Phillips blog

Previously on { feuilleton }

• John Osborne’s Dorian Gray

• 20 Sites n Years revisited

• The last circle of the Inferno

• 20 Sites n Years by Tom Phillips

Arthur Zaidenberg’s À Rebours

“It had not been able to support the dazzling splendour imposed on it…”

It was a novel without a plot and with only one character, being, indeed, simply a psychological study of a certain young Parisian who spent his life trying to realize in the nineteenth century all the passions and modes of thought that belonged to every century except his own, and to sum up, as it were, in himself the various moods through which the world-spirit had ever passed, loving for their mere artificiality those renunciations that men have unwisely called virtue, as much as those natural rebellions that wise men still call sin. The style in which it was written was that curious jewelled style, vivid and obscure at once, full of argot and of archaisms, of technical expressions and of elaborate paraphrases, that characterizes the work of some of the finest artists of the French school of Symbolistes. There were in it metaphors as monstrous as orchids and as subtle in colour. The life of the senses was described in the terms of mystical philosophy. One hardly knew at times whether one was reading the spiritual ecstasies of some mediaeval saint or the morbid confessions of a modern sinner. It was a poisonous book.

The corrupting French novel which Lord Henry Wotton gives to Dorian Gray is never named by Oscar Wilde but its identity is no secret. À Rebours (Against Nature) by Joris-Karl Huysmans was published in 1884 and Wilde, Whistler and others were immediately impressed by what amounts to a manual for the lifestyle of a Decadent Aesthete. Wilde fell sufficiently under its spell to have Dorian Gray in the later chapters of his own novel indulge his senses much like Huysmans’ protagonist, Des Esseintes; where Des Esseintes grows poisonous blooms and fills his room with exotic perfumes, Dorian Gray luxuriates over a hoard of precious stones.

À Rebours features lengthy descriptions of Symbolist art, with particular attention given to Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon. Yet despite the visual description Arthur Zaidenberg’s illustrations are the only ones I’ve come across to date. The book may be influential but it seems too obscure to have attracted illustrators. Zaidenberg’s drawings from a 1931 edition are executed in a woodcut style not far removed from Frans Masereel’s earlier work in books such as Die Stadt (1925), and as such the style is fashionably spare, not necessarily the right choice for a work concerned with sensory delirium. (This Zaidenberg street scene from 1937 shows a definite Masereel influence.) I’d much rather have seen Harry Clarke illustrate Huysmans. Zaidenberg’s drawings are also curious for their foregrounding of the sexual content which makes me think this edition may have been sold on the basis of a salacious reputation. The scene below, for example, doesn’t occur in the novel but can be implied from the description of Des Esseintes meeting a schoolboy in the Avenue de Latour-Maubourg.

“Never had he experienced a more alluring relationship.”

The complete (?) set of Zaidenberg’s illustrations can be seen here. Pages from a later artists’ manual, Anyone Can Draw, are at VTS.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• John Osborne’s Dorian Gray

• Because Wilde’s worth it

• Whistler’s Peacock Room

• Dorian Gray revisited

• Frans Masereel’s city

• The Poet and the Pope

• The Picture of Dorian Gray I & II

John Osborne’s Dorian Gray

I wrote recently about John Selwyn Gilbert’s television play, Aubrey, an hour-long drama concerning the artist Aubrey Beardsley. The play was only screened once in 1982 and, like most one-off studio works of the period, is unavailable on DVD. John Osborne’s 1976 adaptation of The Picture of Dorian Gray is a welcome exception to this neglect and can be acquired in a box set along with three BBC productions of Wilde’s plays and a more recent Wilde documentary.

The stage plays are decent enough although the cast in the 1952 film version of The Importance of Being Earnest takes some beating. Dorian Gray is for me the essential work in the collection, even if its 100-minute running time cuts the story to the bone. The principal attraction in an entirely studio-bound work with few actors is the leads, and for this we have two great performances from John Gielgud as Lord Henry and Jeremy Brett as artist Basil Hallward. The tragic Dorian is played by Peter Firth who has difficulty keeping up with these heavyweights, especially in the later scenes when the story concentrates more fully on his predicament. Matters aren’t helped by his Yorkshire accent which frequently rises to the surface in a manner that would surely raise eyebrows in Mayfair drawing rooms.

Lord Henry & Basil Hallward admire the portrait.

Maldoror illustrated

Les Chants de Maldoror by Corominas (2007).

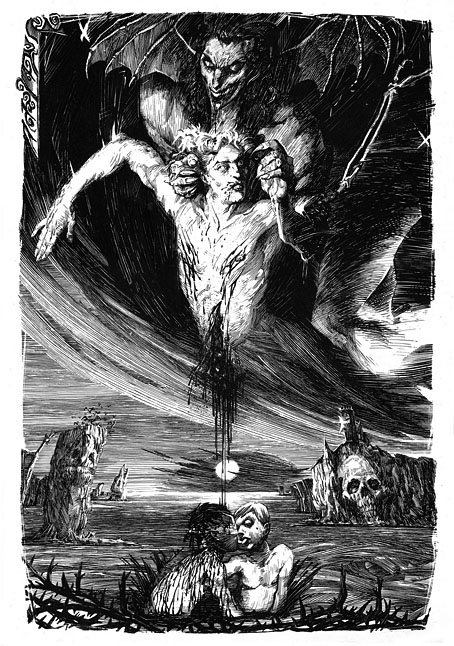

There seems to be no escaping from HP Lovecraft just now, the illustration above having been created for a PDF publication entitled CTHULHU, Cómics y relatos de ficción oscura, produced by these people. The Cthulhu-zine seems to be unavailable but you can see more of these splendid illustrations, based on Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror (1869), at Dorian Gray BD. The artist, Corominas, has an additional blog showcasing more commercial work.

Les Chants de Maldoror by Jacques Houplain (1947).

Lautréamont’s delirious masterpiece isn’t exactly the easiest book to illustrate but the Corominas drawings certainly capture some of its ferocious energy. The Surrealists were big Maldoror enthusiasts, of course, and did much to establish Lautréamont’s current reputation. Salvador Dalí produced a series of engravings for a Skira edition in 1934 although his drawings look less like illustrations of the text than a rifling of the artist’s usual preoccupations. The picture above by Jacques Houplain is one of a series of twenty-seven engravings produced for a French edition in the 1940s. More recently, Jean Benoît created (among other things) a Maldororian dog and there’s even been an attempt at a comic-strip adaptation from Hernandez Palacios. On the whole I prefer the Corominas pictures but then I’m biased towards that style of drawing which owes something to all the comic artists and illustrators influenced by Franklin Booth.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

• The etching and engraving archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Franklin Booth’s Flying Islands

• Carlos Schwabe’s Fleurs du Mal

• The art of Jean Benoît