The Bowie overload this week had me thinking again about Derek Jarman’s unmade science-fiction film, Neutron, an apocalyptic work that would have starred David Bowie if the finance had been forthcoming. Jarman’s description in an earlier post about the film remains tantalising:

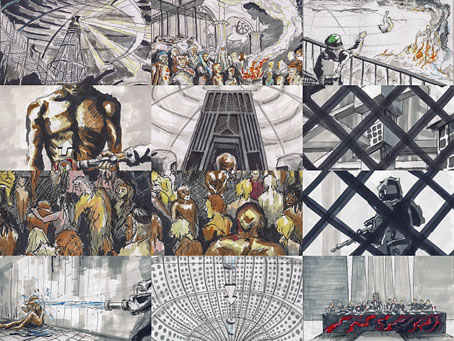

There are six published manuscripts of Neutron, which zig-zag their anti-heroes Aeon and Topaz across the horizon of a bleak and twilit post-nuclear landscape. ‘Artist’ and ‘activist’ in their respective former lives, they are caught up in the apocalypse, where the PA systems of Oblivion crackle with the revelations of John the Divine. Their duel is fought among the rusting technology and darkened catacombs of the Fallen civilization, until they reach the pink marble bunker of Him. The reel of time is looped—angels descend with flame-throwers and crazed religious sects prowl through the undergrowth. The Book of Revelations is worked as science fiction.

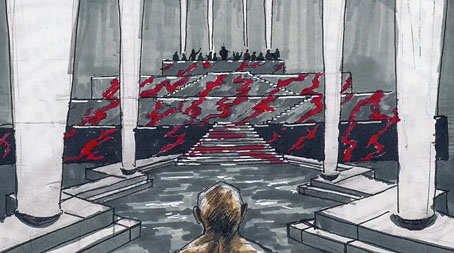

Lee [Drysdale] and I pored over every nuance of this film. We cast it with David Bowie and Steven Berkoff, set it in the huge junked-out power station at Nine Elms and in the wasteland around the Berlin Wall. Christopher Hobbs produced xeroxes of the pink marble halls of the bunker with their Speer lighting—that echo to ‘the muzak of the spheres’ which played even in the cannibal abattoirs, where the vampire orderlies sipped dark blood from crystal goblets.

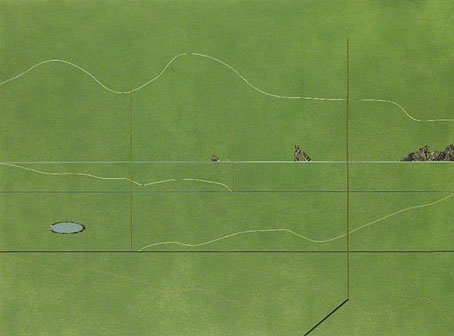

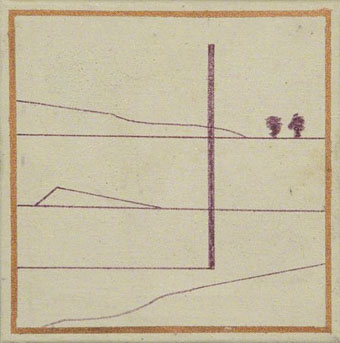

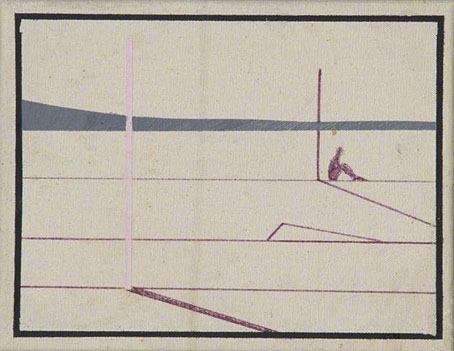

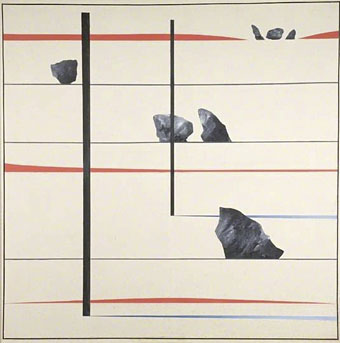

This is one of those great what-if projects along with Jodorowsky’s film of Dune, Nicolas Roeg’s Flash Gordon, and others, so it was a surprise to discover a handful of recent designs for Neutron produced by students at the Wimbledon College of Art. The video here is a short collection of stills by Jonny Blackmore. There’s another of his pieces here, and further designs by Gabrielle Cole here and here. I’m guessing that these were part of a college assignment but if anyone knows otherwise please leave a comment. As to the original Neutron, some version of the script must still exist (Jon Savage was apparently involved in later stages) as must Christopher Hobbs’ designs. Maybe we’ll see them in a book one day.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Derek Jarman’s Neutron