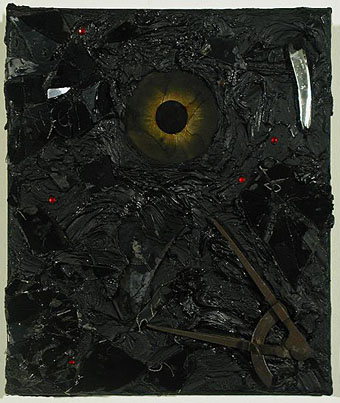

Extending the recent pagan theme, Ubuweb posts Derek Jarman’s determinedly occult and oneiric film, In the Shadow of the Sun (1980), notable for its soundtrack by Throbbing Gristle. This was the longest of Jarman’s films derived from Super-8 which he made throughout the 1970s between work as a production designer and his feature films. He never saw the low resolution, grain and scratches of Super-8 as a deficiency; on the contrary, for a painter it was a means to achieve with film stock some of the texture of painting. Michael O’Pray described the process and intent behind the film in Afterimage 12 (1985):

In 1973, Jarman shot the central sequences for his first lengthy film, and most ambitious to date, In the Shadow of the Sun, which in fact was not shown publicly until 1980, at the Berlin Film Festival. In the film he incorporated two early films, A Journey to Avebury a romantic landscape film, and The Magician (a.k.a. Tarot). The final sequences were shot on Fire Island in the following year. Fire Island survives as a separate film. In this period, Jarman had begun to express a mythology which he felt underpinned the film. He writes in Dancing Ledge of discovering “the key to the imagery that I had created quite unconsciously in the preceding months”, namely Jung’s Alchemical Studies and Seven Sermons to the Dead. He also states that these books “gave me the confidence to allow my dream-images to drift and collide at random”. The themes and ideas found in Jubilee, The Angelic Conversation, The Tempest and to some extent in Imagining October are powerfully distilled in In the Shadow of the Sun. Jarman’s obsession with the sun, fire and gold (which spilled over in the paintings he exhibited at the ICA in 1984) and an ancient mythology and poetics are compressed in In the Shadow of the Sun with its rich superimposition and painterly textures achieved through the degeneration “caused by the refilming of multiple images”. Jarman describes some of the ideas behind In the Shadow of the Sun:

“This is the way the Super-8s are structured from writing: the buried word-signs emphasize the fact that they convey a language. There is the image and the word, and the image of the word. The ‘poetry of fire’ relies on a treatment of word and object as equivalent: both are signs; both are luminous and opaque. The pleasure of Super-8 is the pleasure of seeing language put through the magic lantern.” Dancing Ledge p.129

Ubuweb also has some of the short films which were used as raw material for the longer work: Journey to Avebury (1971) (with an uncredited soundtrack by Coil), the Kenneth Anger-esque Garden of Luxor (1972), and Ashden’s Walk on Møn (1973).

Update: The Ubuweb films have been removed so I’ve taken out the links. The one for In the Shadow of the Sun now goes to a copy at YouTube.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Derek Jarman at the Serpentine

• The Angelic Conversation

• The life and work of Derek Jarman