No Blu-ray as yet but this is another excellent BFI release so it looks and sounds fantastic. There’s been some grumbling that the 1971 director’s cut is still being embargoed by Warner Brothers but when the rest of the film looks so pristine I find it difficult to get worked up over a few missing shots of writhing nuns. Among the extras there’s an early Ken Russell short, Amelia and the Angel (1958), and a second disc of supplementary material, including Paul Joyce’s 48-minute documentary about the making of the film, Hell on Earth. Inside the booklet there’s a photo of set designer Derek Jarman looking very young and sweet. A few screen grabs follow to make Russell enthusiasts in Region 1 jealous. (Hi Thom!)

Tag: Derek Jarman

Derek Jarman’s music videos

Duggie Fields in It’s A Sin

A hidden Derek Jarman film lies scattered among a handful of music videos from the 1980s, something you can pretend you’re seeing flashes of in the promo shorts the director was making whilst trying to raise money for his last few feature films. A recent re-watch of Caravaggio reminded me of these, recalling a remark Jarman made that his video for the Pet Shop Boys’ It’s A Sin was the first time anyone allowed him to use 35mm film. Among other things, that promo features artist Duggie Fields with a gilded face, one of a number of little in-jokes that Jarman aficionados can retrieve from these shorts. Running through them in sequence you get a skate through familiar visuals, from the masks and mirrors flashed into the camera in Broken English, to the Super-8 fast-forwards of The Smiths and Easterhouse films, with plenty of flowers and ritual fires along the way.

Broken English

This isn’t a complete list since not everything is on YouTube. Even if it were I wouldn’t link to anything by the wretched Bob Geldof for whom Jarman made two promos. Needless to say some are more sympathetic to Jarman’s obsessions than others: Marianne Faithfull’s film is a fascinating short that provides a link via the singer between Jarman and Kenneth Anger. The Bryan Ferry film, on the other hand, is a bland piece for a bland song. Suede and The Smiths seemed to have let Derek do what he liked. Well done, boys.

Broken English (1979) by Marianne Faithfull (featuring Witches’ Song, The Ballad of Lucy Jordan and Broken English).

Dance With Me (1983) by The Lords of the New Church.

Willow Weep For Me (1983) by Carmel.

Broken English

Dance Hall Days (1983) by Wang Chung.

Tenderness Is A Weakness (1984) by Marc Almond.

Windswept (1985) by Bryan Ferry.

The Queen Is Dead

Panic (1986) by The Smiths.

Ask (1986) by The Smiths.

The Queen Is Dead (1986) by The Smiths | Long version

1969 (1986) by Easterhouse.

Whistling In The Dark (1986) by Easterhouse.

So Young

It’s A Sin (1987) by the Pet Shop Boys.

Rent (1987) by the Pet Shop Boys.

So Young (1993) by Suede.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Derek Jarman’s Neutron

• Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

• The Tempest illustrated

• In the Shadow of the Sun by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman at the Serpentine

• The Angelic Conversation

• The life and work of Derek Jarman

John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica

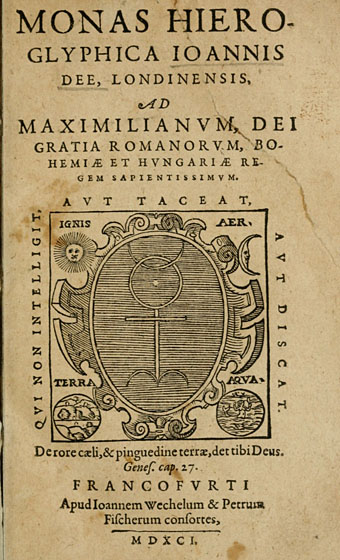

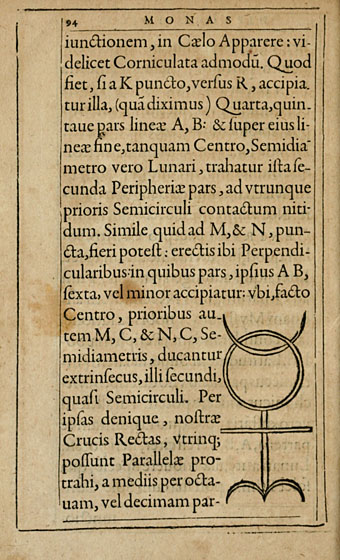

I swear I didn’t go hunting for this. Among the various library collections at the Internet Archive one can find The Getty Alchemy Collection, a substantial gathering of very old alchemical texts scanned in a variety of formats. John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica caught my eye during a random search, a third edition of his treatise from 1564 in which he describes his Monas Hieroglyphica, a glyph designed to combine symbols of the Sun, the Moon, the Elements and Fire in a single figure.

The glyph also intentionally resembles a human form, and Dee relates its individual parts to various astrological and chemical symbols. I’ve mentioned before that Dee scholar Derek Jarman deliberately based Prospero on John Dee in his 1979 film of The Tempest, giving the magus a scrying wand shaped to resemble the Monas Hieroglyphica.

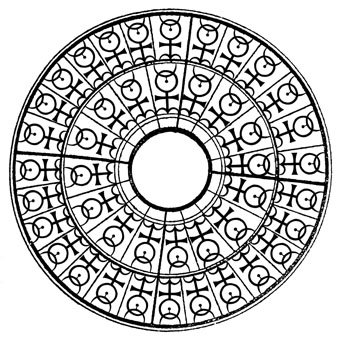

I produced my own variations on the glyph in 2009 when working on the cover of Jeff VanderMeer’s novel, Finch. The symbol recurs in Jeff’s fictional city of Ambergris and I seem to recall there being some discussion about including this doorway design somewhere in the book. In the end it was incorporated into the cover design in a rather subtle fashion. I think this is the first time the design alone has appeared in public.

The Internet Archive has a few other Dee-related items, including Lists of manuscripts formerly owned by Dr. John Dee; with preface and identifications (1921), a 500-page book by antiquarian and ghost story writer MR James.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

• Alchemically Yours

• Laurie Lipton’s Splendor Solis

• The Arms of the Art

• Splendor Solis

• Amphitheatrum Sapientiae Aeternae

• The Tempest illustrated

• Cabala, Speculum Artis Et Naturae In Alchymia

• Digital alchemy

• Designs on Doctor Dee

Derek Jarman’s Neutron

Tilda Swinton in The Last of England (1988).

John Dee turned up in Derek Jarman’s Jubilee after scenes from an earlier script about the Elizabethan magus were grafted onto the punk dystopia. Jarman’s career was to be littered with these unrealised projects, the strangest of which was Neutron, an apocalyptic science fiction film he was planning following the comparative success of The Tempest in 1979. The description he gives in his “Queerlife”, Dancing Ledge, is as follows:

There are six published manuscripts of Neutron, which zig-zag their anti-heroes Aeon and Topaz across the horizon of a bleak and twilit post-nuclear landscape. ‘Artist’ and ‘activist’ in their respective former lives, they are caught up in the apocalypse, where the PA systems of Oblivion crackle with the revelations of John the Divine. Their duel is fought among the rusting technology and darkened catacombs of the Fallen civilization, until they reach the pink marble bunker of Him. The reel of time is looped—angels descend with flame-throwers and crazed religious sects prowl through the undergrowth. The Book of Revelations is worked as science fiction.

Lee [Drysdale] and I pored over every nuance of this film. We cast it with David Bowie and Steven Berkoff, set it in the huge junked-out power station at Nine Elms and in the wasteland around the Berlin Wall. Christopher Hobbs produced xeroxes of the pink marble halls of the bunker with their Speer lighting—that echo to ‘the muzak of the spheres’ which played even in the cannibal abattoirs, where the vampire orderlies sipped dark blood from crystal goblets.

If that doesn’t whet your appetite I don’t know what would. Later drafts of the script were written with Jon Savage. If the film had been made it might well have been terrible, of course, but Christopher Hobbs, who worked with Jarman on later films, as well as on Velvet Goldmine and the BBC’s Gormenghast, would at least have made it look great. David Bowie is very good in The Man Who Fell to Earth but his acting is seldom as successful elsewhere. Steven Berkoff would have been a better bet but a Bowie film would have received far more attention. Bowie discusses his involvement in a 1999 interview here (and also slags off Velvet Goldmine…booo!).

All this was happening circa 1980 when Reagan and Thatcher had just begun their insidious reigns and the Cold War was moving into a new era which generated a great deal of apocalyptic anxiety. Jarman’s response to all of this materialised in 1988 with The Last of England, his bleakest film, and a work in which we can perhaps see some of the nightmare scenes which Neutron would have conjured. I’ve never liked The Last of England very much but it contains a few sequences worth savouring, especially shots of the luminous Tilda Swinton dancing through the wasteland devastation. There’s a fragment of that here with her ripping her dress to pieces accompanied by the voice of Diamanda Galás. Meanwhile, does David Bowie still have the production designs for Neutron? If so, when do we get to see them?

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

• The Tempest illustrated

• In the Shadow of the Sun by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman at the Serpentine

• The Angelic Conversation

• The life and work of Derek Jarman

Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

Prospero (Heathcote Williams) and Miranda (Toyah Willcox), The Tempest (1979).

The Shakespeare who spun The Tempest must have known John Dee; and perhaps through Philip Sidney he met Giordano Bruno in the year when he was writing the Cena di Ceneri—the Ash Wednesday supper in the French Ambassador’s house in the Strand. Prospero’s character and predicament certainly reflect these figures, each of whom in his own way fell victim to reaction. John Dee, with the greatest library in England, skrying for the angels Madimi and Uriel (so nearly Ariel)—all of which is recorded in the Angelic Conversations—ended up, in his old age, penniless in Manchester. Bruno was burnt for heresy.

Ten years of reading in these forgotten writers, together with a study of Jung and his disciples proved vital in my approach to both Jubilee and The Tempest. As for the black magic which David Bowie thought I dabbled in like Kenneth Anger, I’ve never been interested in it. I find Crowley’s work dull and rather tedious. Alchemy, the approach of Marcel Duchamp, interests me much more.

Derek Jarman, Dancing Ledge (1991).

Damon Albarn’s opera Doctor Dee has been all over the news this week following its premier as part of the Manchester International Festival. Last weekend one of the press ads was announcing this as an “untold story”, as though no one had given much thought to the Elizabethan magus prior to Mr Albarn’s arrival. Neither the ads nor anyone associated with the production will be in a hurry to tell you that the idea for the opera came from Alan Moore who’s had a fascination with John Dee’s life and work for many years. Albarn and fellow Gorillaz cohort Jamie Hewlett approached Alan about a collaboration a couple of years ago; Alan agreed to write something on the condition that Gorillaz provide a contribution to Alan’s magazine, Dodgem Logic. They agreed, Alan set to work, having suggested John Dee as a good subject then the whole thing fell apart: Gorillaz said they were too busy to accommodate themselves to the magazine’s generous deadlines so Alan told the pair that he was now too busy to have anything further to do with their opera. This is all old news (and being a Dodgem Logic contributor I have a partisan interest in the story) but it’s worth noting since the opera will be playing elsewhere once it’s finished its Manchester run so we’ll continue to hear about it. The point is that the subject matter was Alan Moore’s choice, not Damon Albarn’s; if Alan had decided to write something about Madame Blavatsky (say) we’d now be reading reviews of Blavatsky: The Opera. Albarn can at least be commended for staying with the subject. Despite John Dee’s exile in Manchester being part of the city’s history (among other things he helped organise the first survey of the streets) you can bet the apes from Oasis have never heard of him.

Richard O’Brien as John Dee in Jubilee (1978).

All of which had me thinking how John Dee, a maverick intelligence of the Elizabethan era, has a tendency to attract equally maverick intelligences in later eras. Derek Jarman’s work returns to John Dee often enough to make the magus a recurrent theme in his films, from the scenes in Jubilee (1978) (part of an earlier script) where he’s portrayed by Richard O’Brien showing Elizabeth I the future of her kingdom, to The Tempest (1979) where Prospero’s wand is modelled on Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica, to The Angelic Conversation (1987) which borrows its title from Dee’s scrying experiments and finds via the sonnets another connection between John Dee and Shakespeare (Ariel being the contrary spirit whose magic allows a vision of the future in Jubilee). By one of those coincidences which make you think there must have been something in the air during the mid-70s, Michael Moorcock’s novel Gloriana, or The Unfulfill’d Queen was published the year Jubilee premiered, a fantasy in which the Elizabethan court is blended with its fictional counterpart from Spenser’s The Faerie Queen, and which features a Doctor John Dee as the queen’s Councillor of Philosophy. (If you want to stretch the connections further, Jenny Runacre who plays Elizabeth in Jubilee had earlier portrayed Miss Brunner in the film of Moorcock’s The Final Programme.)

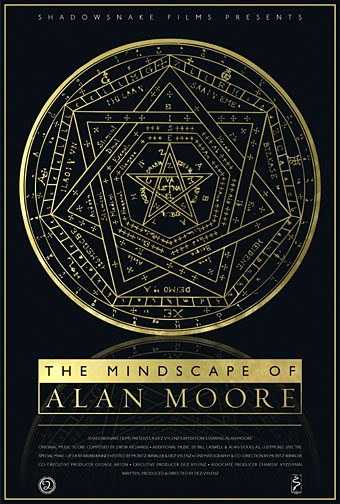

My 2009 poster design for The Mindscape of Alan Moore, a documentary by Dez Vylenz. John Dee’s Sigillum Dei Aemeth appears in the film so I used this as the principal motif for the packaging design and DVD interface.

Reading the reviews it’s impossible to tell how Alan’s libretto might have fared on stage compared to the work which is now showing, the content of which draws on Benjamin Woolley’s excellent biography, The Queen’s Conjuror. Alan and Benjamin Woolley can both be found among the interviewees in a Channel 4 documentary about John Dee broadcast in the Masters of Darkness (sic) series in 2001. For those keen to delve beyond the stage show, Derek Jarman’s films are all on DVD, of course, while fragments of Alan’s libretto can be found in the fourth edition of Strange Attractor along with his notes for the rest of the opera. Charlotte Fell Smith’s life of Dee from 1909, for many years the standard study of the man, can be found online here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Tempest illustrated

• Robert Anning Bell’s Tempest

• In the Shadow of the Sun by Derek Jarman

• Designs on Doctor Dee

• Derek Jarman at the Serpentine

• The Angelic Conversation

• The life and work of Derek Jarman