How I miss Robert Hughes. In print or on the television screen he was one of those rare people whose appearances you didn’t want to miss. On television especially, a medium where he excelled when discussing art or architecture. As I said when his death was announced in 2012, the first two words I wrote here (on 13th February, 2006) were “Robert Hughes”, introducing an extract from a Hughes piece that ran in The Guardian earlier that day. An impromptu choice, as was the launch date, but greeting the world with a pointer to his words felt right somehow: begin as you mean to go on.

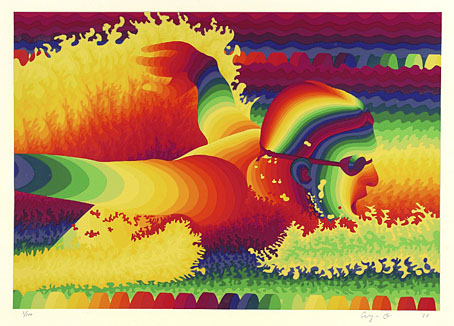

The Mona Lisa Curse was Hughes’ last television essay, made for the UK’s Channel 4 in 2008. After I’d rewatched The Shock of the New two years ago I followed the series with a delve into as many of his films as I could find. The Mona Lisa Curse was one that I’d missed when it was broadcast, and I couldn’t find a decent copy during the retrospective binge. Happily it’s finally turned up at (yes) the Internet Archive. Hughes’ subject this time is the commodity fetishism of the art world, and the growth of money as the dominant factor in the creation, dissemination and discussion of art today. The cult of pictorial celebrity that blossomed around the Mona Lisa when it was brought to New York in 1962 is seen by Hughes as a key moment in a shift of perception that took place in the way that art was viewed in the 20th century. The pernicious effect of money on the art world had already been addressed by the chapter that Hughes added to the book editions of The Shock of the New, a piece which charted the explosive growth of the art market in the 1980s. The Mona Lisa Curse looks at all that has happened since, with American museums turned into global brands, and the ownership of art (especially anything made by a reputable artist) being seen in terms of investment as much as aesthetics.

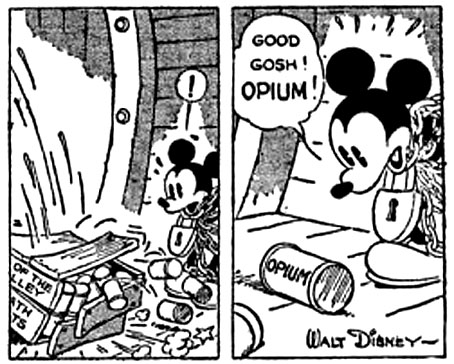

Money has long been a factor in the production of Western art, the traditional gilded picture frame evolved because the paintings inside those frames were intended for wealthy homes. Hughes’ argument here is that the situation has never been as bad as it is today. I’ve been making similar complaints since the 1990s—whatever else they might think they’re doing, the majority of successful contemporary artists are creating exclusive objects for the ownership of the very rich—but you seldom see a complaint like this defined so well or given such a prominent platform. (Yes, unsellable art exists: land art, installations, performances, ephemeral works. Most art is still a unique object of some sort, one that can be sold and resold.) Hughes emphasises that outside the illegal drug trade, art is the largest unregulated market in the world. With billions of dollars changing hands every year nobody complicit in any part of the exchange is going to criticise the situation so long as they’re in a position to receive a portion of that money, however small.

Hughes was 70 when he made this film, although he seemed much older in his later years as a result of a near-fatal car accident in 1999. His bullish, stumbling figure is contrasted with shots of him as he was in the 1970s, including extracts from a film made shortly after he’d landed the job of art critic for TIME magazine. The clips that show him with long hair, dressed in a cut-off denim jacket, are a reminder that while in London he was friends with the other ex-pat Australians at Oz magazine. The Mona Lisa Curse, which was directed by Mandy Chang, may not have been intended as a final statement at the end of a career but it’s hard to avoid that impression when you watch it now. If Hughes’ comments about the art market seem like the curmudgeonly complaints of an old man, consider this for a moment:

With the aplomb of a banker, you’ll end up in the most hideous living-rooms in the world. The coffee-table bears the sanitized book of your work, and the magazine next to it illustrates your patron’s good taste, status and investment rule.

That was much a younger Derek Jarman, writing in 1982 when the present situation had barely begun. In the 1980s art could still make its presence felt outside the galleries even if it was only through causing some minor outrage, as with the fuss in 1989 when US politicians took exception to public money being used to exhibit works by Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano. Nobody cares today what artists do in galleries, the culture wars are being fought elsewhere. Pictorial celebrity and monetary value is all that the art world has left to capture the attention of the wider public.

I was wondering how to end this piece but the news this week has done it for me: “Magritte’s Surrealist Masterpiece Sets $121.2 Million Auction Record“. “The brand recognition of Magritte is incredibly strong,” says a New York dealer, discussing the artist as though he was a product on a supermarket shelf. Which painting will be the first to sell for a billion dollars? Place your bets now.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Rebel Ready-Made

• The Shock of the New

• Robert Hughes, 1938–2012