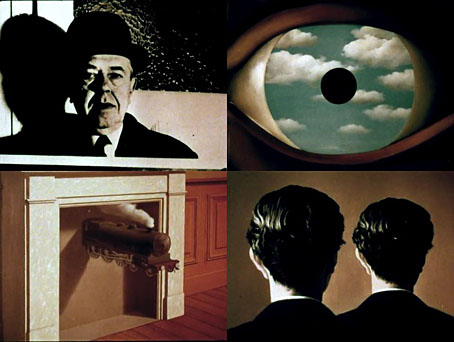

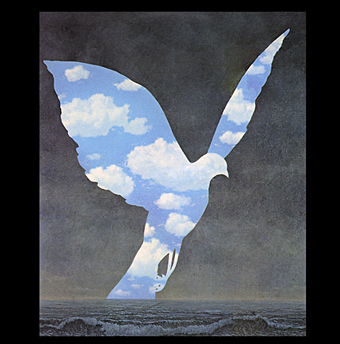

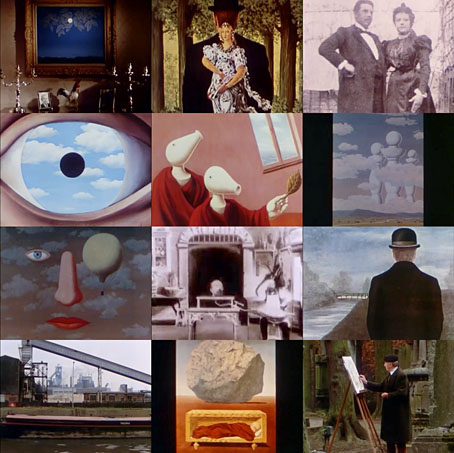

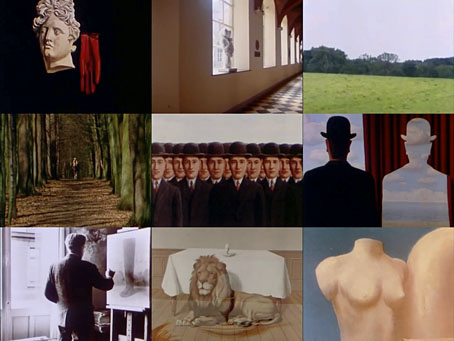

Another short film about René Magritte’s paintings, The False Mirror was made three years after the artist’s death in 1970, a time when his work had started to receive widespread international attention. Prior to the 1960s Magritte wasn’t exactly unknown but it wasn’t until the arrival of Pop Art that his paintings began to be reappraised. The production credits for The False Mirror are surprising for such a short piece, the film being directed by art critic David Sylvester (whose book of interviews with Francis Bacon is essential), and photographed by Bruce Beresford, later to become a well-regarded film director. Among the voices reading from the artist’s statements is ELT Mesens, another Belgian artist and friend of Magritte’s whose presence in the later incarnation of the British Surrealist Group gave that small society some authentic gravitas. (George Melly talks about Mesens and the British Surrealists in this film.) The commentary runs over familiar ground: descriptions of the artist’s childhood encounter with a painter in a cemetery (also referred to in Magritte, ou la lecon de chose), and the details of his mother’s suicide (dramatised in David Wheatley’s film). I’d been wondering recently what Magritte might have made of the increasingly excessive prices being paid for his artworks. One of the comments here provides a possible answer when he says he’d be happy if people destroyed his paintings.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Magritte, ou la lecon de chose

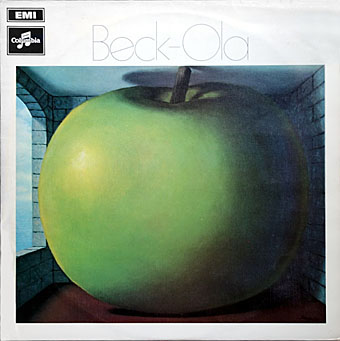

• René Magritte album covers

• Monsieur René Magritte, a film by Adrian Maben

• George Melly’s Memoirs of a Self-Confessed Surrealist

• The Secret Life of Edward James

• René Magritte by David Wheatley