Liu Hui Wen’s “Call of Cthulhu”

And other forgotten masterworks of Chinese SF.

Tag: Cthulhu

New things for April

Several disparate pieces of news worth mentioning recently, so here they are gathered together.

• Some of my Lovecraft art is to be featured in a lavish limited edition volume from Centipede Press.

Artists Inspired by HP Lovecraft

Centipede Press is now accepting pre-orders.

A unique art book available in a cloth slipcase edition and leather deluxe edition.• Cloth edition in slipcase—2,000 copies—400 pages, four color, sewn with cloth covers, enclosed in a cloth covered slipcase. Front cover image, black embossing, two ribbon markers, fold-outs, detail views.

• The first 300 orders will receive a numbered copy with a special slipcase and a hardcover folder with an extensive suite of unbound illustrations. $395 postpaid.

• Leather edition in traycase—50 copies—400 pages, four color, sewn with full leather binding, enclosed in a giant size traycase. Front cover image debossed on front, two ribbon markers, fold-outs, detail views, signed by most living contributors. $2,000 postpaid.

This huge tome features over forty artists including JK Potter, HR Giger, Raymond Bayless, Ian Miller, Virgil Finlay, Lee Brown Coye, Rowena Morrill, Bob Eggleton, Allen Koszowski, Mike Mignola, Howard V Brown, Michael Whelan, Tim White, John Coulthart, John Holmes, Harry O Morris, Murray Tinkelman, Gabriel, Don Punchatz, Helmut Wenske, John Stewart, and dozens of others.

The field has never seen an art book like this—indeed, it is an art anthology unlike anything ever published before. Many of these works have never before seen publication. Many are printed as special multi-page fold-outs, and several have detail views. The book is filled with four color artwork throughout, all of it printed full page on rich black backgrounds. A special thumbnail gallery allows you to overview the entire contents of this 400-page book at a glance, with notations on artist, work title, publication information, size, and location, when known.

HP Lovecraft fans will simply have to have this book. Because of its sheer size and scope, this book will never be reprinted and will sell out very quickly. Twenty years down the road people will be paying huge prices for this book because of its scope and the quality of reproductions. This is the HP Lovecraft fan’s dream come true. Don’t miss it!

Yes, it is indeed expensive but this is a book for serious collectors.

• Bryan Talbot‘s new book, Alice in Sunderland, is finally out. Read a review of it here.

• Arthur Magazine is being summoned back from Avalon, which is excellent news. To celebrate, Jay Babcock has posted Alan Moore‘s history of pornography in its entirety here.

left to right: Donald Cammell, Dennis Hopper, Alejandro Jodorowsky & Kenneth Anger.

One of my favourite photographs of all time shows four directors at the Cannes Film Festival in 1971, all dolled up in their wildest afghan-and-ascot, hairy-hippy finery, and all of them on the cusp of what should have been majestic, transformative, transgressive careers in cinema that by and large never came to fruition. It was not to be—if only it had been.

• John Patterson tell you why we need Jodorowsky as much as we ever did.

Update: And while we’re at it, Eddie Campbell also has a new book out, The Black Diamond Detective Agency. Great playbill cover design.

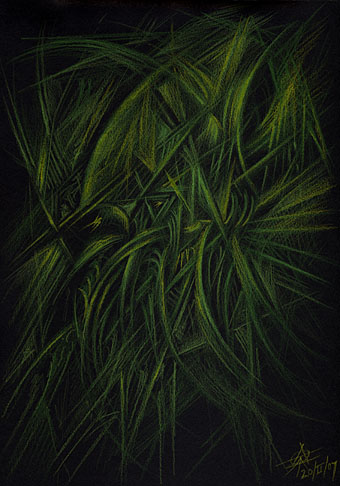

Cubist Cthulhu

Well maybe it isn’t, but the phrase occurred to me a few days ago so I thought I’d try some sketching and see what emerged. In one interpretation of The Call of Cthulhu it’s conceivable that Lovecraft intended his abomination to look like this, given the description of R’lyeh in the story:

Without knowing what Futurism is like, Johansen achieved something very close to it when he spoke of the city; for instead of describing any definite structure or building, he dwells only on broad impressions of vast angles and stone surfaces—surfaces too great to belong to anything right or proper for this earth, and impious with horrible images and hieroglyphs. I mention his talk about angles because it suggests something Wilcox had told me of his awful dreams. He said that the geometry of the dream-place he saw was abnormal, non-Euclidean, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours. Now an unlettered seaman felt the same thing whilst gazing at the terrible reality.

An alien monstrosity might be even more terrifying if it didn’t resemble anything organic or remotely earthly. For a more traditional impression of the Spawn from the Stars, my drawing from The Great Old Ones can be found here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Down with human life

Sam Leith is engrossed by a formidable essay on the father of ‘weird fiction’.

Sam Leith is engrossed by a formidable essay on the father of ‘weird fiction’.

HP Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life

by Michel Houellebecq

tr by Dorna Kazheni

intro by Stephen King

256pp, Weidenfeld & Nicolson

£10 (pbk)

Saturday, August 12, 2006

The Daily Telegraph

“I AM SO BEASTLY TIRED of mankind and the world that nothing can interest me unless it contains a couple of murders on each page or deals with the horrors unnameable and unaccountable that leer down from the external universes.” So wrote Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890–1937). His extraordinary body of work can be seen as a sustained effort to fill that prescription.

The founding father of what has become known as “weird fiction”, Lovecraft was not a congenial figure. Tall, ugly, misanthropic, snobbish, reclusive, he hated people in general, and people of other races in particular. More or less nothing happened in his life. He was 32 before he kissed a woman and his brief, unsuccessful and wholly unexpected marriage put paid to love for good. He died of intestinal cancer at 47.

His literary concerns were as follows: unkillable tentacled beings from beyond space worshipped by cannibal death cults; hideous prodigies of miscegenation; gibberings from the abyss; indecipherable languages of madness; insane architectural geometries; colours outside any nameable spectrum. Lovecraft has nothing in common with Anita Brookner.

On the surface, he has very little in common with Michel Houellebecq, either. What they seem to share, though, is an aggressive misanthropy. In this consistently engaging essay, an infatuated Houellebecq argues that Lovecraft’s work pioneered a sort of anti-literature: a great shout of “NO!” to human life.

Lovecraft was not just unrealistic, Houellebecq argues, but anti-realistic: the devotee of a sort of malevolent sublime. Religious writers see our animal lives as validated by the notion that beyond our perception lies something infinitely larger, more ancient and more benevolent. Lovecraft played with the opposite idea. If there’s something else, why should we imagine it would be benevolent? How much more likely that we have, here, a pretty disgusting animal existence; but that if we caught a whiff of what lies outside it, we’d go instantly mad—if we were lucky.

Very little of what Lovecraft wrote conforms to the conventional canons of what literature should be doing. His characters are more or less interchangeable: drab men with drab jobs, no pasts and no futures. They are there to bear witness, to have the living daylights frightened out of them and, if they are unlucky, to be “devoured by invisible monsters in broad daylight at the Damascus market square”. There’s no interest in human life, or money, or sex. The stories don’t start in the real world and amble into horror: they start midway through the screaming hab-dabs and turn up the volume from there producing what Houellebecq calls “an open slice of howling fear”. The involuted and clumsily baroque sentences disapproved of by Lovecraft’s detractors are serving, then, a singular purpose: to pile more on—to generate an intoxicating fever pitch of rhetoric.

Houellebecq’s essay is often perverse, sometimes jejune, more than occasionally downright silly. He attributes more consistency of philosophical purpose to Lovecraft than, I think, a sensible reading of the “great texts”—”The Call of Cthulhu” (1926), ‘The Colour Out of Space” (1927), ‘The Dunwich Horror” (1928), “The Whisperer in Darkness” (1930), “At the Mountains of Madness” (1931), “The Dreams in the Witch House” (1932), ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth” (1932) and “The Shadow Out of Time” (1934)—will bear.

And he on more than one occasion dismisses Lovecraft’s critics, with Houellebecquian arrogance, as “idiots” and such like. But his essay is both a formidable literary performance in itself, a work of real imaginative sympathy, and a consistently engrossing intellectual workout. It bursts with new ideas, and new ways of thinking about this oddest of writers. Bolstered by an introduction by Stephen King, and a pair of first-rate Lovecraft stories, it’s worth anyone’s tenner.

Lovecraft, as Houellebecq observes, “writes for an audience of fanatics—readers he was finally to find only years after his death”. That his work at last found those readers is beyond question. The “Cthulhu Mythos”, like Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, has become a place in which devotees live.

Ever since Lovecraft’s friend August Derleth completed some of his unfinished stories after his death, fantasy writers have done more than imitate Lovecraft’s approach: they have set their stories in his universe. The internet now throws up thousands of references to the mythos, allusions to the dread Necronomicon, and artists’ imaginings of Lovecraft’s monsters.

When I was a child, there was a Call of Cthuthu role-playing game. There’s even an internet cartoon series, “Hello Cthulhu“, that pits the Elder Gods against the overpowering cuteness of “Hello Kitty”. “Hi there! Would you like a cookie?!?” asks a fwuffy kitty with a ribbon in her hair. “No, actually. I would hate to have a cookie, you vapid waste of inedible flesh!” retorts Cthulhu. Lovecraft wouldn’t have liked it, I don’t think. But somewhere, sepulchrally, he might have been flattered.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Le horreur cosmique

Le horreur cosmique

I’ll be in Paris this week so some French-related postings are in order.

I’ll be in Paris this week so some French-related postings are in order.

Michel Houellebecq’s HP Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life (which I still haven’t read) has been in the news again recently, with a number of reviews appearing in UK newspapers and magazines, most of which present the by-now rather tired spectacle of reviewers who normally wouldn’t give any of this nasty pulp stuff a second thought having to take Lovecraft seriously because Houellebecq is a serious author. (“He’s a bad writer!” they bleat. And Lou Reed is a bad singer; you’re missing the point, you fools.) The Observer last week had one of the better ones. Last year the Guardian published an extract from Houellebecq’s book.

Curious how often it requires the French to make the Anglophone world look anew at marginalised elements of its own culture; Baudelaire championed Edgar Allan Poe, it was French film critics who gave us the term “film noir” when they identified a new strain of American cinema and the Nouvelle Vague writers and filmmakers were the first to treat Hitchcock as anything other than a superior entertainer. The French have always liked Lovecraft so it was no surprise to me at least when Houellebecq’s book appeared.

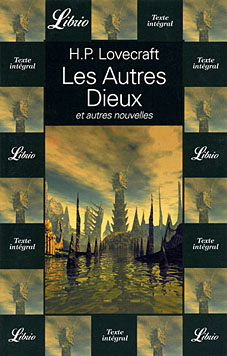

Oddly enough, the only association I’ve had so far with French publishing is the use of my 1999 picture of Cthulhu’s city, R’lyeh, on the cover of a reprint of HPL stories from Houellebecq’s publishing house (above). Something I’ll be looking for in Paris if I have the time will be more of Philippe Druillet‘s Lovecraft-inflected work. Druillet has been working with the imagery of cosmic horror since the late 60s and even illustrated the work of William Hope Hodgson, one of HPL’s influences and an English writer the broadsheet critics have yet to hear about. Take a look at these pictures for stories written before the First World War then go and look at some stills from the latest Pirates of the Caribbean movie. What was once the preserve of Weird Tales and other pulp magazines is now mainstream culture.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Davy Jones

• Charles Méryon’s Paris