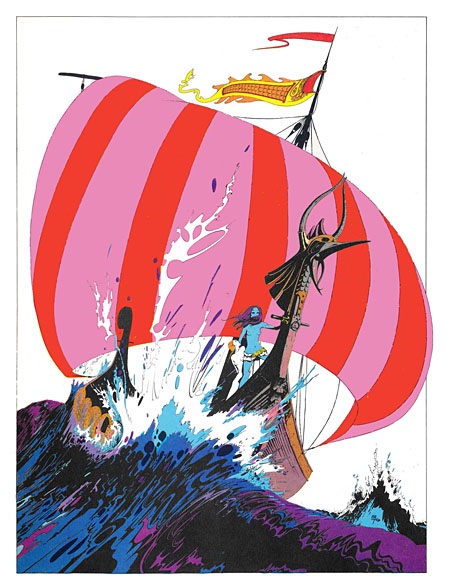

Cover by Simon Heath with Nicolas Crombez.

October, as I’ve noted before, is drone month, and this year I finally decided to catch up with the most recent instalments in the series of Lovecraft-themed albums that Cryo Chamber have been releasing each year since 2014. I’m still waiting for the discs to arrive—the Shoggoth Mail has been taking its time to slither here from Kracow—but Bandcamp happily assuages any impatience by offering immediate downloads. All of these albums are a collaborative effort between a varying roster of Cryo Chamber artists, with the contributions being blended together to create disc-long tracks (usually two discs to an album) that offer audio portraits of the gods or beings of the Cthulhu Mythos. The contributors do their best to maintain a consistent mood (and, where necessary, the same key) so there aren’t any of the abrupt exchanges you often get in music mixes. As to the identity of the groups or individuals involved, I could name names but as I’m not familiar with their work outside these releases there’s not much I can say about them.

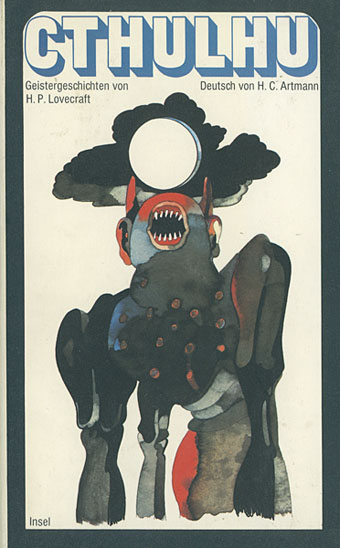

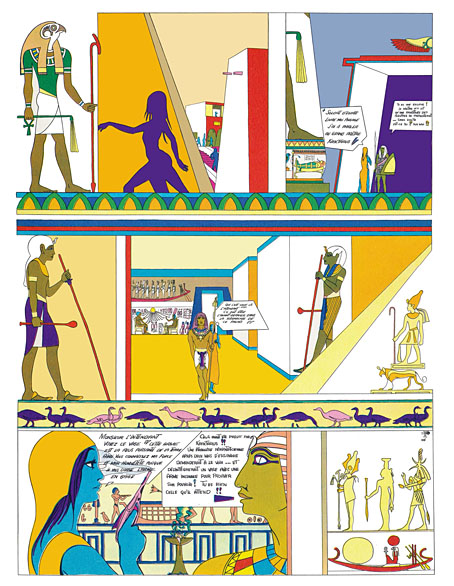

Covers by Simon Heath.

Lovecraftian music used to be little more than one-off tracks on rock albums but, as with Lovecraftian illustration, there’s a lot more fully-realised material to be found today. One of the things I like about the Cryo Chamber albums is that they’re wholly instrumental (the “Cthulhu fhtagn” intonation on Cthulhu is a rare exception), and with each piece being an hour or more in length I find them very amenable as soundtracks for illustration sessions. Cryo Chamber specialises in a variety of dark ambient music that’s more evocative than the abstract equivalents produced by artists like Thomas Köner: Gothic doom and apocalyptic science fiction are recurrent themes. Since cosmic horror tends to be a blend of Gothic doom and apocalyptic science fiction it was almost inevitable that one or more of HP Lovecraft’s monstrous extraterrestrials would eventually raise its tentacles somewhere in the Cryo Chamber discography. This type of music is a better match for weird fiction than most of the rock music derived from Lovecraft’s stories, in part because it resembles the kinds of atmospheric timbres that you find on the better horror soundtracks. There’s more substance here than Köner’s “grey noise” but rhythm is minimised or omitted altogether, and there’s a general avoidance of overt musicality. One of the precursors of the Cryo Chamber sound, Lustmord, established the form in 1992 with The Monstrous Soul, an album that quotes liberally from Jacques Tourneur’s The Night of the Demon while borrowing track titles (IXAXAAR, The Daathian Doorway) from Kenneth Grant’s eldritch occult philosophies.

Covers by Simon Heath.

The Cryo Chamber Collaborations began with Cthulhu, the only single-disc release, and one which I seem to play the most. Subsequent releases have dealt with Lovecraft’s other Mythos gods—Azathoth (2015), Nyarlathotep (2016), the only three-disc release), Yog-Sothoth (2017) and Shub-Niggurath (2018)—before working through the extended Mythos with albums devoted to Hastur (2019), Yig (2020), Dagon (2021) and Tsathoggua (2022). Some of the albums are more sonically illustrational than others: Cthulhu and Dagon evoke the oppressive chasms of the oceanic deep, while Nyarlathotep, Hastur and Yig offer intimations of the Middle East, justified in the case of Nyarlathotep’s pharaonic aspect, less so for the others. Yog-Sothoth, meanwhile, features a succession of chiming tones like those produced by Tibetan bowl gongs. Lovecraft’s fiction tells us little about the actual nature of Yog-Sothoth aside from vague references like the one in The Horror in the Museum, a story co-written by Lovecraft and Hazel Heald, in which we read of “a congeries of iridescent globes…stupendous in its malign suggestiveness.” Not an easy thing to represent in music yet the Yog-Sothoth album has its own mood and character which sets it apart from the others in the series. The most recent release, Tsathoggua, honours Clark Ashton Smith’s loathsome toad god with swathes of abrasive noise and repeated eruptions of a cthonic bass tone like those used by Deathprod on the baleful Treetop Drive.

Now that the Cryo Chamber series has made use of all the primary deities of the Mythos cycle, plus some of the secondary ones, I’ve been wondering where it may go next. There are many minor deities (or entities) created by the generations of writers that followed Lovecraft’s lead (see this list for details) but few of the names of these beings have the authority of Lovecraft’s nomenclature. They also lack the textual reinforcement that the Mythos gives to entities that would otherwise have been limited to mentions in only one or two stories. I suppose we’ll find out whether the label will be continuing the series soon enough. The albums as they currently stand run for over 18 hours in total. That’s almost enough to soundtrack the entirety of Halloween.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Daikan by Thomas Köner

• Cosmic music and cosmic horror

• Drone month

• Hodgsonian vibrations