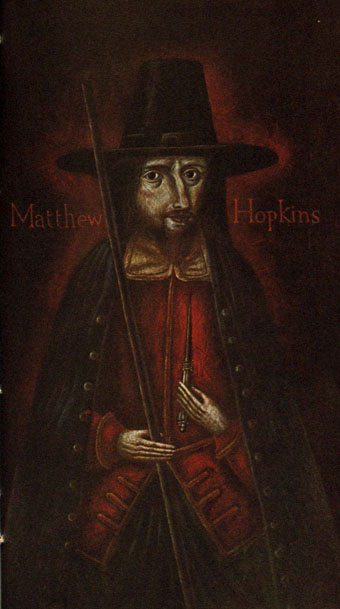

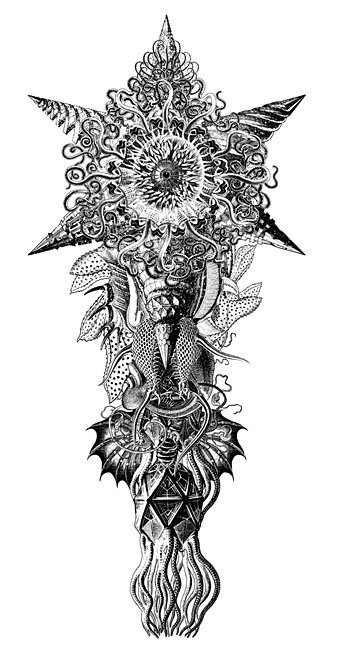

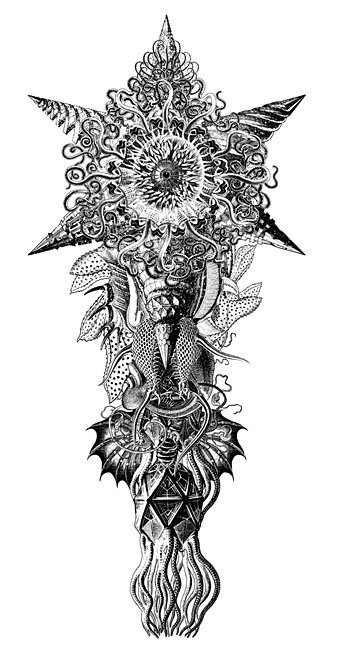

Graphic for the title page and ends of chapters.

I don’t usually post things so far away from publication, but editor Ellen Datlow put these pictures on her Facebook page a few hours ago so I may as well do the same here.

Back in February I bought a Wacom Intuos drawing tablet, something I’ve been using with regularity for the past few months. The Alas Vegas Tarot cards I designed in the summer were the first major attempt at getting used to working with it; Lovecraft’s Monsters, a forthcoming fiction anthology for Tachyon is the second, and I now feel very comfortable working with it. More than that, I’m increasingly pleased with the way it’s possible to combine the drawing techniques I’ve been using for years with the additional possibilities provided by working in Photoshop. As always, it’s the end result that counts but arriving at an end result can be easy or difficult. Some of these illustrations look no different than they would have done had I used ink on paper but they took half the time to create, a considerable benefit when a deadline is looming.

The stories Ellen Datlow has chosen for this collection all present different aspects of monstrosity seen through the lens of Lovecraft’s fiction and his cosmic menagerie. Some are full-on extensions of the Mythos, others are more allusive; all the pieces bar one have been published before but I’d not read any of them so for me this was fresh material. Having spent the past few years saying I was finished with Lovecraft’s fiction I was excited to be working on this book. The stories are good, and I welcomed the challenge of having to illustrate such a variety of material.

Larger copies of all the pictures can be seen here.

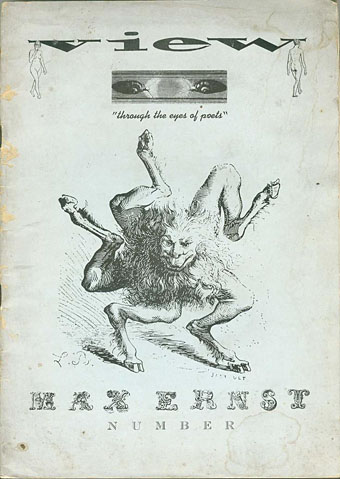

The star-headed thing at the top of this page is another amalgam of elements plundered from Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur and other sources. I’ve leaned rather heavily on Haeckel in the past, something I wanted to avoid here; this serves as a kind of visual punctuation separating the stories.

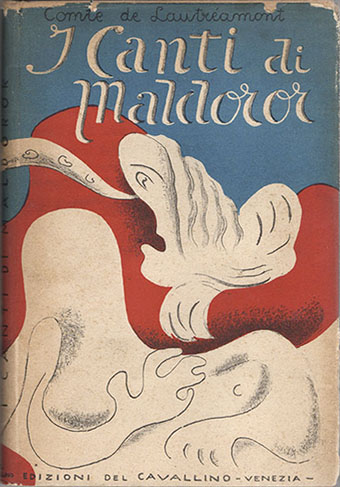

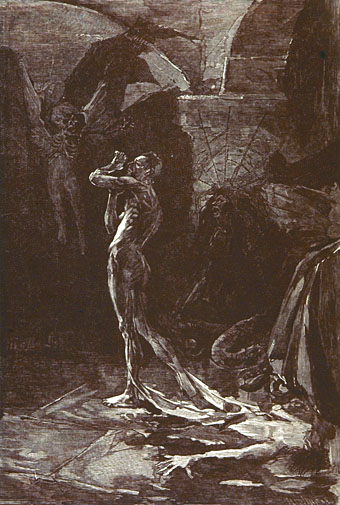

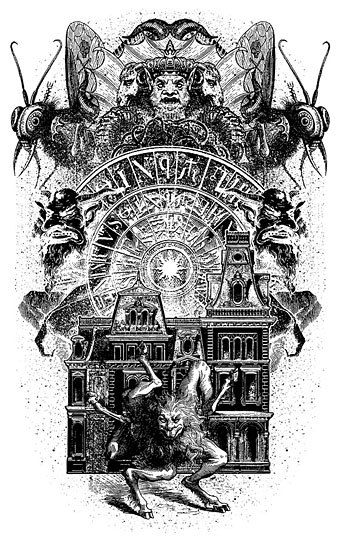

Cthulhu.

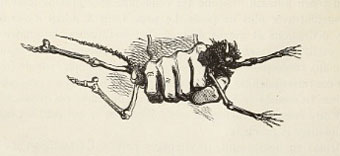

The drawing I’ve called Cthulhu is a piece for the introductory pages. Having already produced a lot of Cthulhoid art I didn’t want to repeat myself. The initial idea was of a tiny human figure faced with something enormous and nightmarish; that could be a vast eyeball or it could be a mouth or some other organ/aperture, the vagueness was intentional. Lovecraft continually impresses upon his readers how difficult things are to describe or apprehend but you seldom find this quality in art based upon his stories. Cthulhu especially has devolved into little more than an outsize man-in-a-rubber-suit à la the Creature from the Black Lagoon. In The Call of Cthulhu the figure on the mysterious statuette is described as having a humanoid shape but Lovecraft doesn’t describe the appalling reality in any detail at all. When Cthulhu is struck by a ship at the end of the story it breaks apart and is then seen recombining, the implication being that the creature is corporeally amorphous.

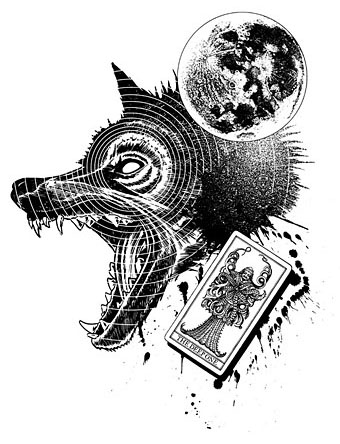

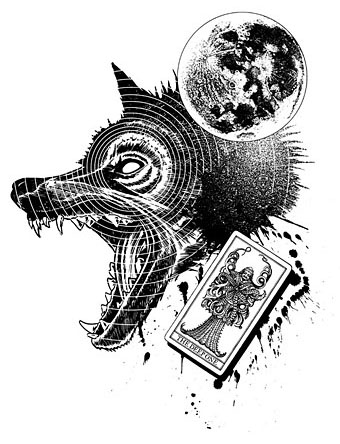

Only the End of the World Again by Neil Gaiman.

Neil Gaiman’s entry concerns a werewolf private detective in Innsmouth. Lovecraft’s decaying fishing village and its inhabitants turn up in several of the stories so care was taken to avoid repetition.

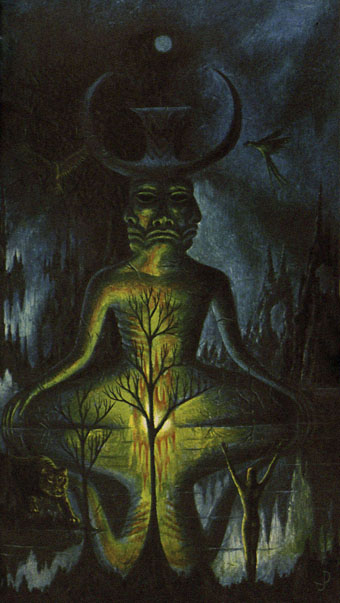

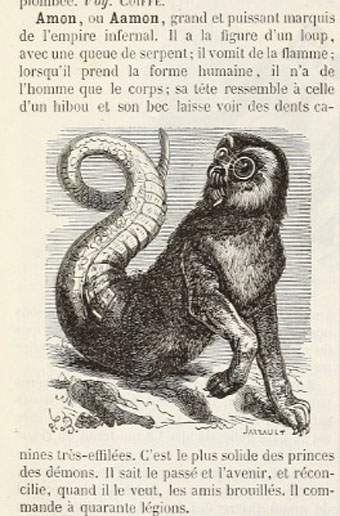

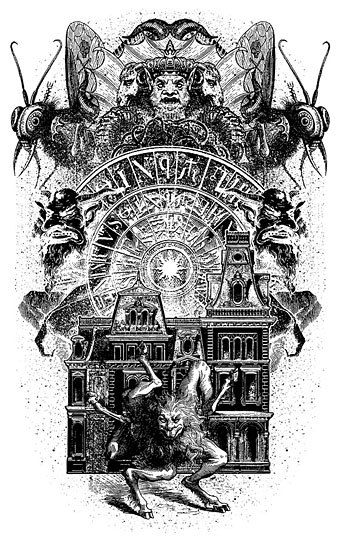

Bulldozer by Laird Barron.

A great story about another detective, a Pinkerton agent this time, hunting his quarry through the Old West. Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal is mentioned so I used some of Louis Breton’s illustrations from the third edition.

Continue reading “Lovecraft’s Monsters”