The recent news from the BFI about their forthcoming collections of Derek Jarman films sent me to YouTube once more in search of a documentary I’d been hoping to see again. Derek Jarman: Know What I Mean… is the film in question, and was posted a few months ago by director Laurens Postma on his own YouTube channel. Postma produced a number of arts features for Channel 4 (UK) in the 1980s, one of which, Six Into One: The Prisoner File, a documentary about the making of Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner, has been mentioned here already. The Jarman film was made in 1988, and I think was the first lengthy television examination of Jarman’s career. It’s still one of the best since the later documentaries tended to be either shortish interview sessions or posthumous works such as Derek (2008) by Isaac Julien and Bernard Rose.

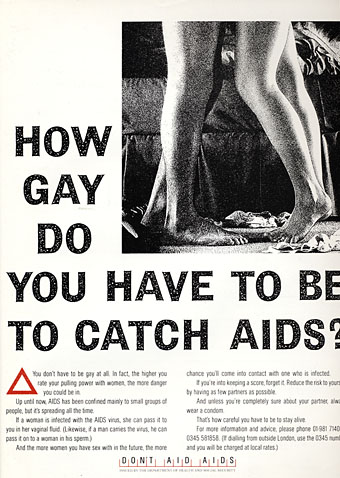

Postma’s film captured Jarman shortly after he’d moved to his cottage at Dungeness, a relocation that was a kind of semi-retirement even though his films were becoming more visible as a result of funding and screening from Channel 4. This was also the period when he was becoming more vocally political thanks to what seemed at the time to be the unending reign of the iniquitous Margaret Thatcher. The Tories of the day had recently announced the now-infamous Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act (discussed in the film as both Clause 28 and—confusingly—Clause 29, the labels by which the amendment was first known), a ruling that forbid councils from promoting homosexuality, especially in schools. The late 80s saw the peaking of anti-gay bigotry in Britain, a reaction against the growing freedoms of the 1970s and, inevitably, the menace of AIDS which was still being regarded as “the gay plague”. Jarman had recently been diagnosed as HIV+, something he discusses here with typical good cheer although the conversation is generally more about art than his health, and about the way his own works were always related to gay sexuality. Jarman was one of many gay artists who welcomed their sexual identity as fixing them in the position of outsiders, and it’s notable how many of his films are concerned with outsider figures. When discussing The Tempest (1979) he compares Prospero’s island to gay sexuality, an uncharted enclave and a home to outcasts where different rules apply. This was still a common view among gay men and lesbians in the 1980s—Jarman’s friends in Coil used to say similar things in their interviews—and very different from today’s drive towards conformity and social assimilation. Postma’s film ends with Jarman on the beach at Dungeness, the perfect zone for a lifelong outsider, midway between the land and the sea.

(Note: the Winston Churchill referred to in the film is the grandson of the famous Prime Minister. Winston Churchill Jr. was an MP in the Thatcher government who tried to bring in a bill banning the public exhibition of “explicit homosexual acts” following Channel 4’s TV broadcast of Jarman’s Sebastiane.)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• David Tibet meets Derek Jarman

• Shooting the Hunter: a tribute to Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman’s landscapes

• Derek Jarman album covers

• Ostia, a film by Julian Cole

• Derek Jarman In The Key Of Blue

• The Dream Machine

• Jarman (all this maddening beauty)

• Sebastiane by Derek Jarman

• A Journey to Avebury by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman’s music videos

• Derek Jarman’s Neutron

• Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

• The Tempest illustrated

• In the Shadow of the Sun by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman at the Serpentine

• The Angelic Conversation

• The life and work of Derek Jarman