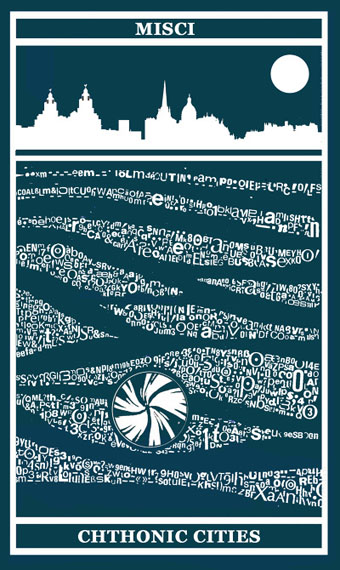

Chthonic Cities by David Chatton Barker. One of a series of Folklore Tapes screenprints available from Bleep.

• The original version of Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising, the one with the Jimmy Page soundtrack that was completed in 1973, has always been described as lost/stolen/buried or otherwise gone forever. So you’d think the news that a print had been discovered recently by Brian Butler would have received greater attention. There’s a screening in Los Angeles this Thursday. When do the rest of us get to see it?

• Chris Marker: A Grin Without a Cat, an exhibition and series of Marker-related events at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. Related: The Encounter of M. Chat & Chris Marker as Told By Louise Traon.

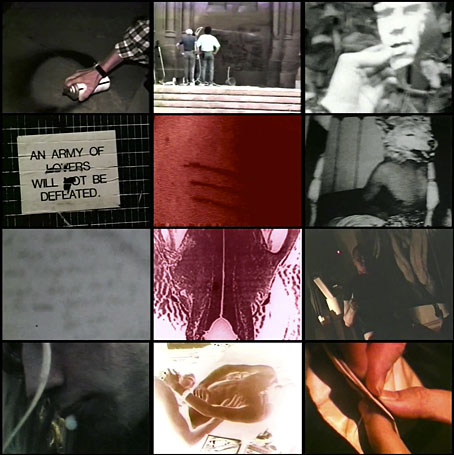

• The trailer for The Gospel According to St Derek, a forthcoming documentary about Derek Jarman. Related: Carl Swanson on why Tilda Swinton is not quite of this world.

Maybe there’s just something conservative at the bedrock of American fiction. […] Or maybe it’s just another symptom of the creeping conservatism that’s infected so many aspects of the culture.

Eric Obenauf talks to author Jeff Jackson whose comments about cultural conservatism could equally be applied to the UK.

• Primitive graphics, inventive graphics, budget Surrealism, and some great theme tunes; it’s Trunk TV, Episode 1: Title Sequences.

• Mixes of the week: Secret Thirteen Mix 110 by Black To Comm, and Intro To Drone For Debcon 1, almost 7 hours of music!

• Joseph Burnett reviews Ett, an album of electronic music by Klara Lewis.

• The Delian Mode (2009), a film about Delia Derbyshire by Kara Blake.

• Extracts from Tokyo Reverse by Simon Bouisson and Ludovic Zuili.

• Dan Piepenbring on The Haunting Illustrations of Alfred Kubin.

• At Strange Flowers: Photos of arcades by Germaine Krull.

• Fish, Fiends, and Fantasy: The Gothic Art of Ian Miller.

• At 50 Watts: Richard Teschner and His Puppets.

• Sonic Foam: Ian Penman on Kate Bush and Coil.

• Lucifer (1968) by The Salt | Experiment IV (1986) by Kate Bush | Methoxy-N, N-Dimethyl (5-MeO-DMT) (1998) by Coil