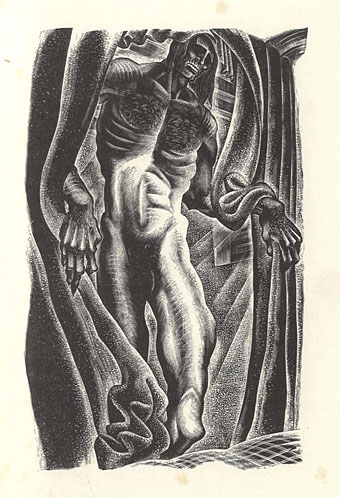

Lynd Ward again, and one of his illustrations for Frankenstein (1934).

• “Julio Mario Santo Domingo was a collector and visionary who filled his homes and warehouses with the world’s greatest private collection related to the subjects of drugs, sex, magic, and rock and roll: a library of more than 50,000 items…” Altered States: The Library of Julio Santo Domingo by Peter Watts catalogues some of the artefacts.

• “His vision of Gay Liberation was deeply, and uniquely, inflected by his study of, and belief, in anarchism.” More on the late Charles Shively: Michael Bronski remembers a pivotal figure in the gay liberation movement.

• William Friedkin’s Sorcerer was released on region-free blu-ray a couple of years ago but it’s being reissued again in the UK for its fortieth anniversary. Julian House has created a series of designs for the insert.

• Electronic musician and podcaster Marc Kate talks to Erik Davis about nihilism, horror movies, New Age music, and transmuting Nazi black metal into the ambient soundscapes of his latest album, Deface.

• “Beware the polished little man“: an extract from The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe by Franziska zu Reventlow which is available now from Rixdorf Editions.

• Another welcome blu-ray release, Sergei Parajanov’s The Colour of Pomegranates appears later this month in a special edition from Second Sight.

• Mixes of the week: FACT mix 626 by Sharp Veins, XLR8R Podcast 515 by Sammy Dee, and Secret Thirteen Mix 236 by Beta Evers.

• The Witch Wave with Pam Grossman is a podcast for bewitching conversation about magic, creativity, and culture.

• Call me by the wrong name: Benjamin Lee on Hollywood’s perennial attempts to straight-wash gay films.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…Ronald Firbank Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli (1926).

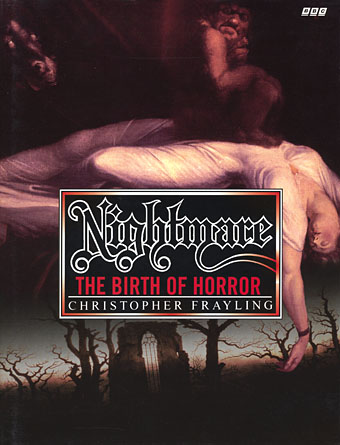

• Zoë Lescaze reviews Frankenstein: The First Two Hundred Years by Christopher Frayling.

• Angry Optimism in a Drowned World: A Conversation with Kim Stanley Robinson.

• Stewart Smith on The Strange World of…Linda Sharrock.

• Colors (1969) by Pharoah Sanders | Frankenstein (1972) by The Edgar Winter Group | Pomegranate (2001) by Transglobal Underground