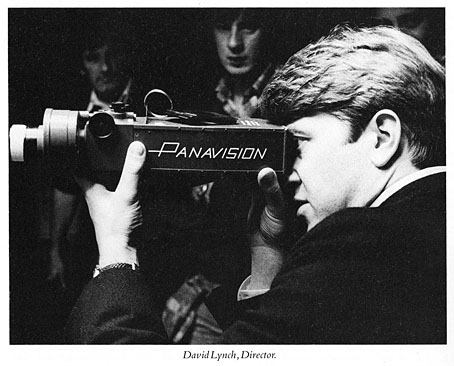

Photo by Frank Connor from The Elephant Man: The Book of the Film (1980).

I feel at a loss for words on this occasion, Lynch’s films have been a continual presence in my life since I saw The Elephant Man in 1981. I’d actually been thinking of watching some of them again, maybe even having a full-on Lynch season the way I did in 2018 when I watched everything in sequence, from his early shorts through to Twin Peaks: The Return which at the time had just been released on disc.

A few random thoughts:

• My first sighting of Eraserhead was on the big video screens at the Hacienda in Manchester in late 1982. Claude Bessy used to play clips from his video collection, all of them silent because a DJ was usually playing music at the same time, so you’d end up seeing confusing, contextless shots from films like A Clockwork Orange, Shogun Assassin, various Andy Warhol films, and so on. I got to see Eraserhead in full shortly after this at a proper cinema on a double-bill with George Romero’s The Crazies. The Romero was fun but the Lynch was a doorway to another world.

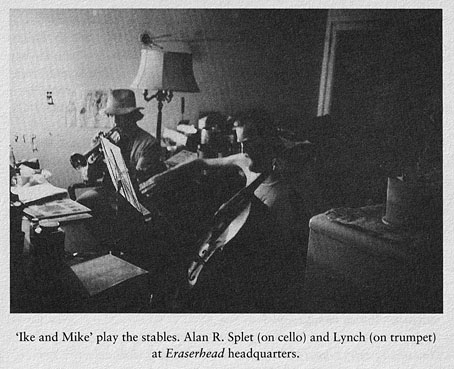

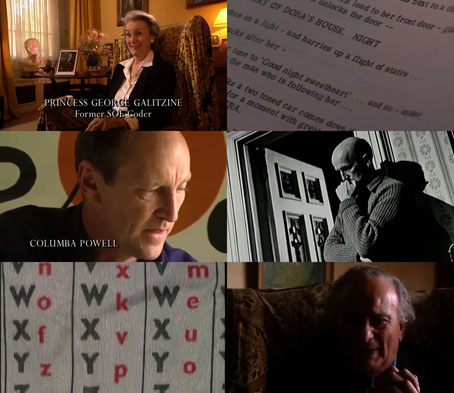

Photo from Lynch on Lynch (1997).

• Anyone writing about Lynch’s early features, especially Eraserhead, ought to mention sound designer Alan Splet. Lynch himself was always full of praise for Splet; the pair worked on the soundtracks together but Splet had a unique way of processing sounds which is all over the early films from The Grandmother on. You can gauge Splet’s sonic invention by watching The Black Stallion, a Lynch-less film for which Splet won an Oscar, where the sounds of panting horses are stranger than anything in any other film about horses or horse-racing. If you were familiar with Splet’s weirdness then his absence from Wild at Heart was a significant loss; Randy Thom is a good sound designer but he’s not in the same league. As Paul Schütze noted in his Splet obituary for The Wire in 1995, the soundtrack of Eraserhead is one of the foundations of the whole “dark ambient” genre of music.

• Some favourite Splet moments in Lynch’s films: the industrial sounds that accompany Treves’ walk through the East End in The Elephant Man; the visit from the Guild Navigator at the beginning of Dune; Jeffrey’s dream in Blue Velvet.

• For all the times I’ve watched Blue Velvet I still don’t know what that thing is hanging on Jeffrey’s bedroom wall.

• Lynch films are dog films.

• It was difficult not to feel like a Lynch hipster in 1990 when the world at large was forced to confront Lynch’s imagination via Twin Peaks and (to a lesser extent) Wild at Heart. We had to endure a year of people who’d spent the past decade ignoring Lynch’s films offering their opinions, along with inane comments such as “But does he have anything to say?” It was a relief when Fire Walk With Me came out and drove away the lightweights. I remember Kim Newman pointing out in his Sight and Sound review that the Twin Peaks prequel was more of a genuine horror film than many films explicitly labelled as such. The same could be said of Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive.

• I was pleased that Lynch was invited to contribute to the Manchester International Festival in 2019; I got to see some of his paintings and also buy Twin Peaks badges and Lynch postcards. Best of all, however, was the two weeks or so when his face was peering out of posters at tram stops and (as he is here) gazing down on pedestrians in my local high street. I’ve mentally tagged that pole as The David Lynch Lamp Post ever since.

Okay, maybe not so lost for words after all…

• Elsewhere:

(offline) Lynch on Lynch (1997), edited by Chris Rodley. 270 pages of interviews which aren’t always very revealing but which still contain a wealth of detail and anecdote about the making of the films. Also a fair amount of discussion about his paintings and other artworks.

(online) 46 issues of Wrapped in Plastic, the Lynch fan magazine.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Lynch dogs

• 42 One Dream Rush

• Through the darkness of future pasts

• David Lynch window displays

• David Lynch in Paris

• Inland Empire