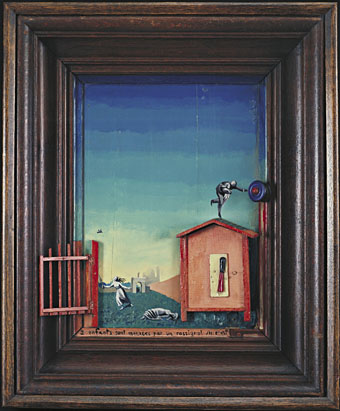

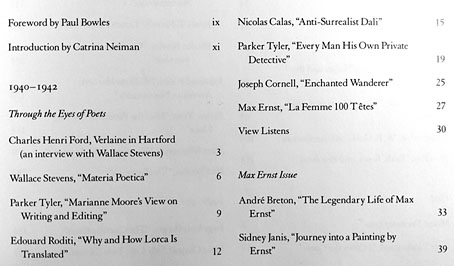

Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924) by Max Ernst.

Another discovery from Charles Henri Ford’s View: Parade of the Avant-Garde. Sidney Janis devotes several pages to one of the earliest Surrealist paintings by Max Ernst, Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale. After describing the picture in detail he makes this comparison:

In 1935, Dalí painted a Nostalgic Echo, obviously of this very picture by Max Ernst. Eleven years divided the two paintings; still the lapse of time has not interrupted a continuity of idea which takes place between them. For now we have the next sequence of events. Ernst’s adolescent with the knife appears again in the Dalí, her gesture identical but free of her earlier emotional tension. We find her contentedly skipping rope, her contour and movement echoed in the belfry as a ringing bell. And here it is the nightingale that is menaced. It alights, and as it does, a shadow moves toward it in the form of a snare. This shadow-snare is thrown by the girl and the rope. Finally, the nimble-footed man no longer leaps the rooftops—he is brought to earth to brood in the shadow of his own senility. Relegated to a humble corner of the foreground portal, he is a sorry sight, while in the belfry-tower which repeats the image of the portal, the feminine form triumphantly dominates the aperture, swinging against the sky. The play of ideas in the two pictures is like a Surrealist game in which one participant carries on where the other leaves off.

Nostalgic Echo (1935) by Salvador Dalí.

Dalí’s paintings frequently quoted other artists but seldom, if ever, the work of his contemporaries so I’m sceptical that Nostalgic Echo is a response or a sequel to the Ernst. But paranoiac-critical-Sherlock Holmes would agree that the comparison is a suggestive one.

Nostalgic Echo (detail).

A more obvious echo for Dalí is Giorgio de Chirico’s The Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (below), where we find a similar girl at play among plastered walls, arched portals and elongated shadows. Three paintings, and three stages in a narrative whose events rearrange themselves depending on the order in which they are viewed.

The Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1914) by Giorgio de Chirico.

Previously on { feuilleton }

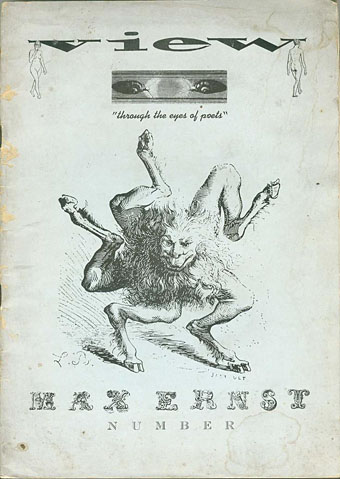

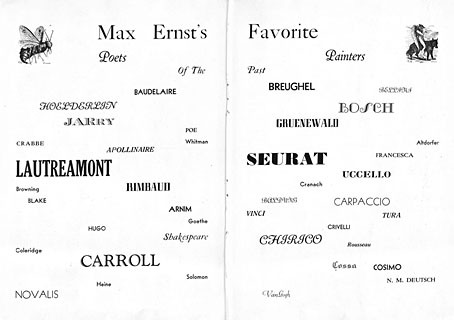

• Max Ernst’s favourites

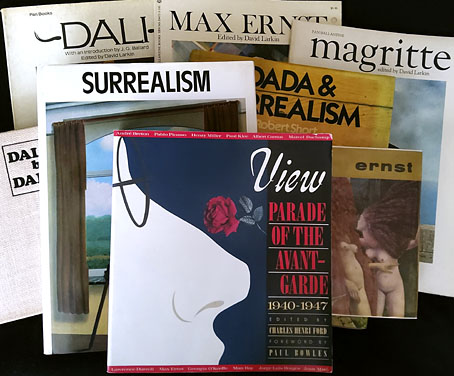

• Viewing View

• Max Ernst album covers

• Maximiliana oder die widerrechtliche Ausübung der Astronomie

• Max and Dorothea

• Dreams That Money Can Buy

• La femme 100 têtes by Eric Duvivier