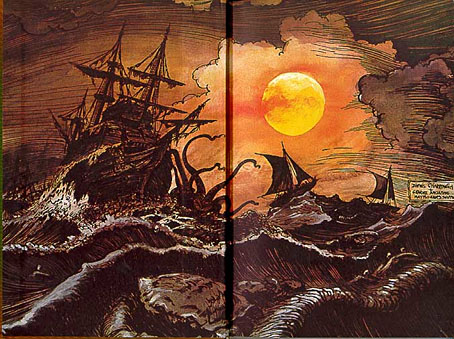

Cover design by Michel Vrana.

This, then, is the book that arrived a fortnight ago when I just happened to be in the midst of a week of tentacle posts. Vampyroteuthis Infernalis: A Treatise, with a Report by the Institut Scientifique de Recherche Paranaturaliste was originally published in Germany in 1987. This new edition is the first translation into English (by Valentine A. Pakis) published by the University of Minnesota Press in their Posthumanities series. It’s 100 pages long with a supplement of squid illustrations by Louis Bec. It is, to say the least, an odd book:

Part scientific treatise, part spoof, part philosophical discourse, part fable, Vampyroteuthis Infernalis gives its author ample room to ruminate on human—and nonhuman—life. Considering the human condition along with the vampire squid/octopus condition seems appropriate because “we are both products of an absurd coincidence…we are poorly programmed beings full of defects,” Flusser writes. Among other things, “we are both banished from much of life’s domain: it into the abyss, we onto the surfaces of the continents. We have both lost our original home, the beach, and we both live in constrained conditions.”

I’m not familiar with Flusser’s other work since I read few academic texts but it seems safe to assume that Vampyroteuthis Infernalis is an exception among the author’s volumes of media and communication theory. The tone is light but not overly comic unless you regard as inherently amusing Flusser’s analysis of an obscure cephalopod—the Vampyroteuthis Infernalis (the name translates as “vampire squid from hell”)—as a useful tool for studying the human condition. The study so far as it goes is along the lines of some of the essays by Jorge Luis Borges rather than any lengthy disquisition, looking at the squid’s existence from a number of angles in order to draw comparisons with human life. You wouldn’t think it easy to talk about “squid culture” or “squid politics” but Flusser manages:

…we are able to imagine cultural structures (“Utopias”) in which even our biological constraints are done away with. The vampyroteuthis cannot fathom Utopias, for the structure of its society is not a cultural product (it is not a “factum”) but rather a biological given (a “datum”). When it engages in politics, it does so against its own “nature”—it commits a violent act against itself. In the end, however, is not all human political activity contra nature?

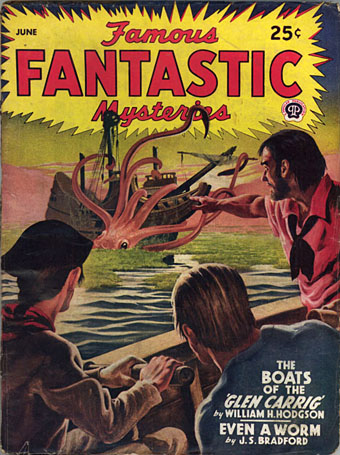

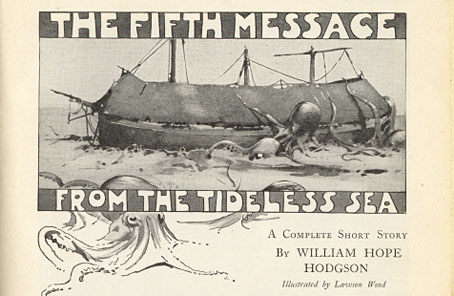

And so on. In Borges terms (for me he’s the obvious touchstone) the book is reminiscent of the Chronicles of Bustos Domecq (1967), a series of deadpan essays about absurd cultural developments credited to one “H. Bustos Domecq” but written by Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares. Flusser lived in Brazil for a number of years so Borges may have been an inspiration. Like Borges, Flusser is learned enough to write convincingly about his subject before he starts evading the reader’s grasp. The opening of Vampyroteuthis Infernalis is a creditable and informative run through the Octopoda taxonomy; later we have references and terminology from Heidegger, and Wilhelm Reich makes a surprising appearance. Many of the parallels are ingenious, such as when Flusser compares our electronic media—the glowing screens of televisions and computer monitors—to the glowing chromatophors on the skin of the squid which the animal uses to communicate in the lightless depths of the sea. Flusser ends on another Borgesian note, describing his “fable” as offering “an image of the self reflected between two facing mirrors”. Perhaps that’s the best way to regard this book: a continual play of reflections all of which would vanish if one of the mirrors were removed.

Those who wish to lose themselves in the reflections can order the book in hardback or paperback direct from the University of Minnesota Press. Elsewhere there’s a fair amount of Vampyroteuthis Infernalis footage on YouTube which reveals the animal in question to be as wonderfully strange as its name would imply.

Previously on { feuilleton }

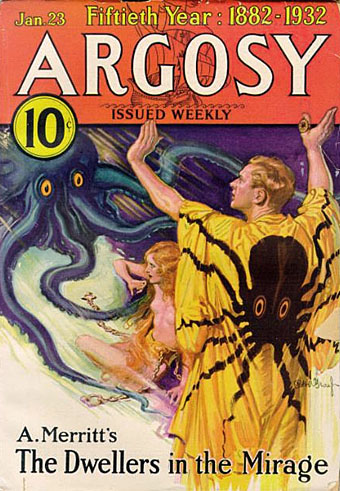

• Le Poulpe Colossal

• Fascinating tentacula