La Edad de Oro (The Golden Age) was a Spanish television show which only ran from 1983 to 1985 but during that time it managed to cause a considerable stir, first by showcasing in lengthy programs many musical groups that would have been unknown to the Spanish public (or the public of their native countries, for that matter), and secondly by scandalising that public with irreligious performances from some of those bands. La Edad de Oro was part of a general attempt to bring Spain up to speed with the rest of European culture following the end of the Franco regime, as a result of which a number of leftfield groups were given far more attention than they would have received in the UK. Psychic TV were one of the groups offered a carte blanche two-hour slot, and I remember Genesis P Orridge mentioning this with some surprise in interviews.

Tuxedomoon’s own edition of La Edad de Oro was broadcast on May 24, 1983. I’ve been fortunate to acquire a pristine copy of a later screening from one of the tape trading sites, and it’s a remarkable thing, cutting between couch interviews with the band members and a complete studio performance of their songs. The latter can been seen on YouTube, of course, so there’s no need to go hunting down rare files. This is the first Tuxedomoon concert I’ve seen, I don’t recall them ever being on British TV although some of their videos must have been screened somewhere. What’s fascinating is seeing how theatrical their performance is. In addition to screening some of Bruce Geduldig’s films on a backdrop, there are shadow vignettes and bits of stage play such as the ropes that bind each of the band members together during The Cage. Later on, Blaine Reininger and Winston Tong graffitise a sheet of film stretched over the stage. (Tuxedomoon’s “Joeboy” designation originated in some San Francisco street art.) I’m wondering if the rope business was borrowed from David Bowie: in the Cracked Actor film he does a similar thing during the Young Americans tour.

Wikipedia has a list of La Edad de Oro‘s artistas invitados not all of which are essential—China Crisis…please—but I’d love to see some of the other editions, the Cabaret Voltaire one especially. Time to go hunting.

Previously on { feuilleton }

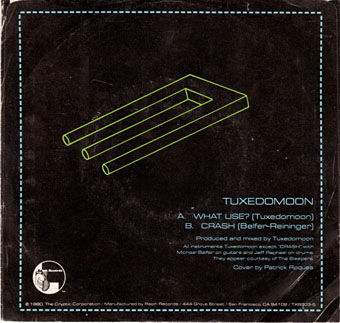

• Tuxedomoon designs by Patrick Roques

• Pink Narcissus: James Bidgood and Tuxedomoon