“Chloromgonfus detectis, a dragonfly that can detect volatile pollutants.” A speculative insect by artist Vincent Fournier.

• “…a modern taxonomist straddling a Wellsian time machine with the purpose of exploring the Cenozoic era…” Butterflies tied together Vladimir Nabokov’s home, science, and writing, says Mary Ellen Hannibal.

• More ghosts: Kira Cochrane on the Victorian tradition of the Christmas ghost story, and Michael Newton on why Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961) remains one of the very best ghost films. No argument there.

• Should you require further persuasion, Daniel Barrow reviews I Am The Center: Private Issue New Age Music In America 1950-1990, an album still receiving heavy rotation in these quarters.

Swords, daggers—weapons with a blade—retained a mysterious, talismanic significance for Borges, imbued with predetermined codes of conduct and honor. The short dagger had particular power, because it required the fighters to draw death close, in a final embrace. As a young man, in the 1920s, Borges prowled the obscure barrios of Buenos Aires, seeking the company of cuchilleros, knife fighters, who represented to him a form of authentic criollo nativism that he wished to know and absorb.

The Daggers of Jorge Luis Borges by Michael Greenberg

• The Junky’s Christmas (1993): a seasonal tale from William Burroughs turned into a short animated film by Nick Donkin and Melodie McDaniel.

• Mixes of the week: Secret Thirteen Mix 101 by Jan Jelinek, and The Conjuror’s Hexmas by Seraphic Manta.

• Meet the 92-year-old Egyptian [Halim El-Dabh] who invented electronic music.

• The Mysterious Lawn Home of Frohnleiten, Austria.

• The Peacock Room at Sammezzano Castle in Italy.

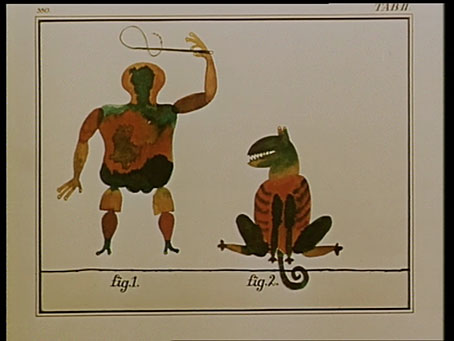

• The Quay Brothers’ Universum.

• Alan Bennett‘s diary for 2013.

• Butterfly (1968) by Can | Butterfly (1974) by Herbie Hancock | Butterfly (1998) by Talvin Singh