Cover artist unknown.

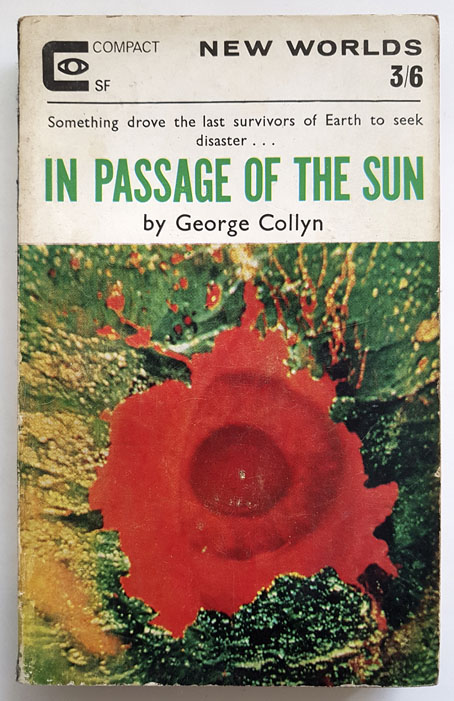

A selection by JG Ballard of six favourite Surrealist paintings, or five Surrealist ones and a Metaphysical picture if you want to be strict about the definitions. These were described but not shown in an essay, “The Coming of the Unconscious”, that Ballard wrote for issue 164 of New Worlds magazine in 1966, something I was re-reading yesterday. I have quite a few of the Moorcock-edited Compact editions of New Worlds, being paperback-sized they used to be a common sight in secondhand bookshops. Issue 164 also includes a guest editorial from Ballard which he fills with a report from his recent viewing of La Jetée, the influential time-travel short by Chris Marker which was receiving its first London screenings.

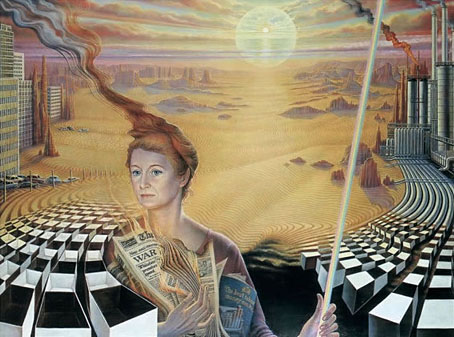

Ballard’s essay is ostensibly a review of two books about Surrealist art but he doesn’t really bother with these, being more concerned with exploring his own thoughts about the paintings which inform so much of his early fiction. It’s a very good piece, especially for the way it interleaves Surrealist theory with the Ballardian concerns found in the “condensed novels” that were eventually published together (with Dalí cover art) as The Atrocity Exhibition in 1970. The following list comes near the end of the piece, and shouldn’t be taken as a definitive selection on Ballard’s part. There’s no Yves Tanguy, for example, even though Tanguy’s art is referred to in The Drought. And no Paul Delvaux either, an artist who Ballard liked enough to commission Brigid Marlin to recreate the two Delvaux paintings that were destroyed in the Second World War. A still-extant Delvaux painting, The Echo, is mentioned in The Day of Forever, a story that Ballard was probably writing around this time and which was published in New Worlds 170.

“The Coming of the Unconscious” was reprinted several times after this: in a story collection, The Overloaded Man (1967), in the first RE/Search Ballard book in 1984, and in the essay and reviews collection A User’s Guide to the Millennium (1996).

The Disquieting Muses (1916–1918) by Giorgio de Chirico

“These mannequins are human beings from whom all transitional time has been eroded, they have been reduced to the essence of their own geometries.”

I’m guessing that this is the original painting. De Chirico was perpetually frustrated that everyone preferred his “Metaphysical” paintings of the 1910s to the endless self-portraits and other dull works he insisted on producing in his later years. In order to keep the income flowing he painted many copies of his older pictures, at least 18 of which are versions of this one, with several backdated to the time of the original. As Robert Hughes put it: “Italian art dealers used to say the Maestro’s bed was six feet off the ground, to hold all the ‘early work’ he kept ‘discovering’ beneath it.”

The Elephant Celebes (1921) by Max Ernst

“Ernst’s wise machine, hot cauldron of time and myth, is the tutelary deity of inner space, the benign minotaur of the labyrinth.”

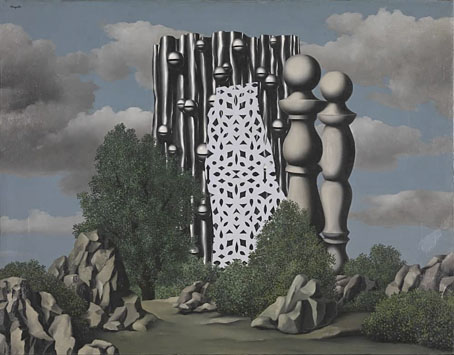

The Annunciation (1930) by René Magritte

“This terrifying structure is a neuronic totem, its rounded and connected forms are a fragment of our own nervous systems, perhaps an insoluble code that contains the operating formulae for our own passage through time and space.”

An interesting choice mainly because Ballard didn’t usually mention Magritte; Dalí, Delvaux and Ernst were the painters he returned to the most. It’s typical, however, for him to choose a landscape.

The Persistence of Memory (1931) by Salvador Dalí

“The empty beach with its fused sand is a symbol of utter psychic alienation, of a final stasis of the soul.”

The one painting that even Dalí’s many detractors tend to like. Ballard, like Dawn Ades and a handful of others, developed his own opinions about Dalí’s oeuvre instead of following the consensus opinion (which often seems more like an unexamined prejudice) that everything the artist did after the 1930s was of little value.

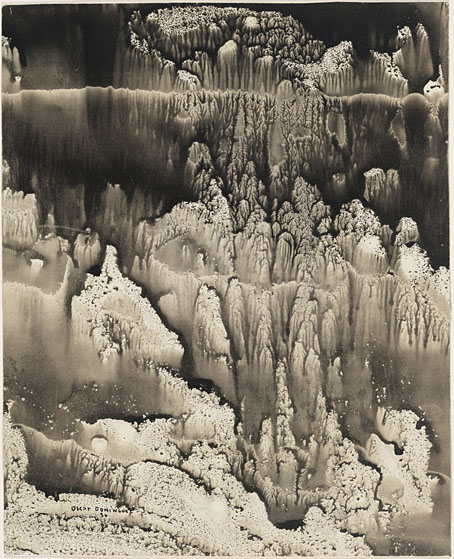

Decalcomania by Óscar Domínguez

“These coded terrains are models of the organic landscapes enshrined in our nervous systems.”

Decalcomania is a process, not a picture, an addition by Domínguez to the many techniques of pictorial automatism (frottage, grattage, fumage, etc) developed by the Surrealists. With this entry you can make your own selection from the Domínguez paintings that use the technique. I chose Untitled (1936).

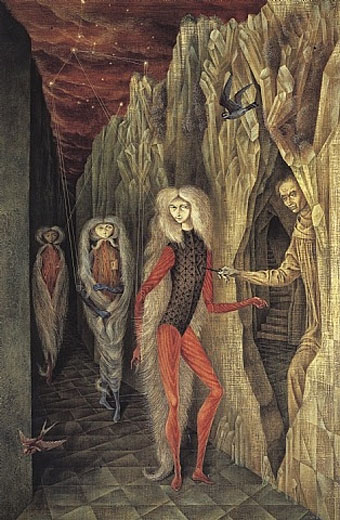

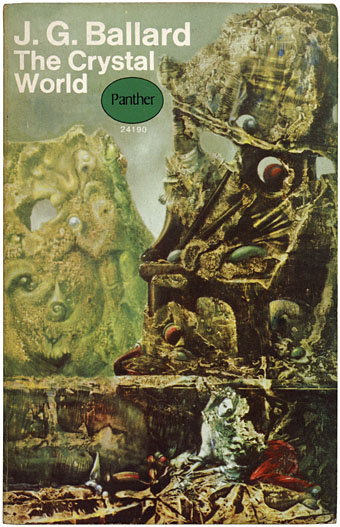

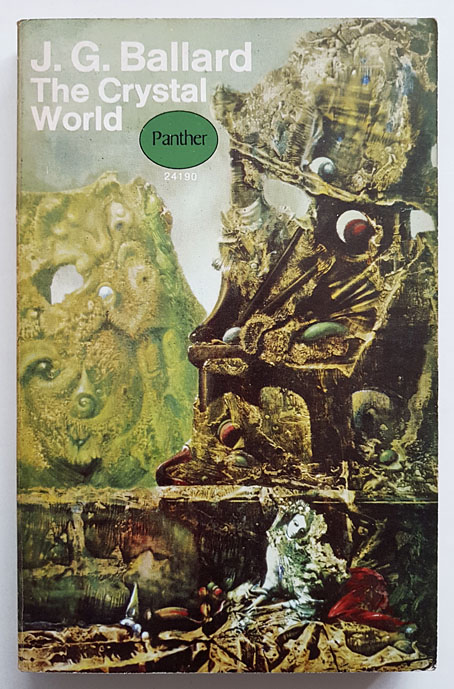

The Eye of Silence (1943–44) by Max Ernst

“The real landscapes of our world are seen for what they are—the palaces of flesh and bone that are the living façades enclosing our own subliminal consciousness.”

My favourite Max Ernst painting, and also a definite Ballard favourite. The Crystal World had just been published when this essay appeared, and both the UK and US editions used this painting on their dustjackets. Panther books followed suit when the UK paperback appeared two years later.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Echoes of de Chirico

• Max Ernst’s favourites

• Ballard and the painters