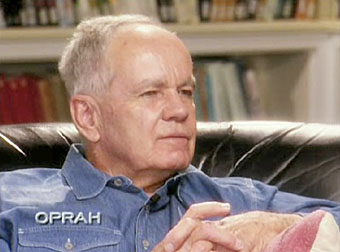

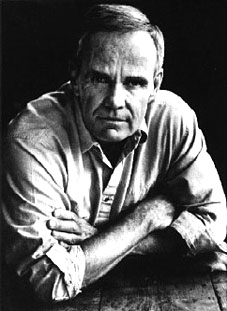

Cormac McCarthy’s appearance on Oprah’s Book Club—his first television appearance ever—was screened last week. You can watch it online for free on her site although you need to register first. The interview is presented in chunks and only lasts for about twenty minutes but it was worthwhile for all that, even if it is chopped to pieces in that manner typical of American daytime TV.

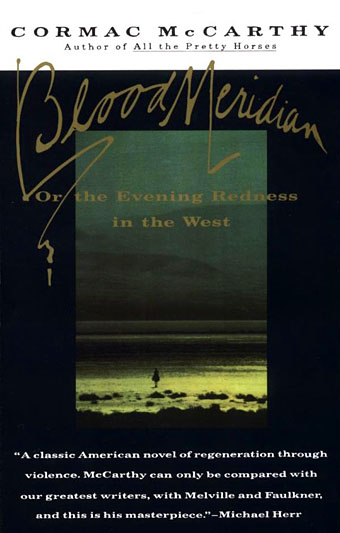

Most of the discussion skated on the surface but I was surprised (and pleased) when Oprah mentioned having read several of his books, including his ferocious masterwork, Blood Meridian. Main topic was The Road, of course, but we also got to hear something about Cormac’s dedicating himself to a life of precarious unemployment in order to have the freedom to write. He’s playing my tune but I imagine many of Oprah’s viewers would have struggled to comprehend that decision. Faulkner’s name was mentioned, and James Joyce when they talked about the lack of punctuation in his prose. In the end it was enough to simply see the man as a human being sat in a chair. And kudos again to Oprah for championing his work.

Meanwhile, The Sopranos screened its final episode on Sunday night. I watched the last couple of seasons via BitTorrent so I’m privy to the controversial ending which I won’t reveal here even though plenty of news sites have done so already. All I’ll say is I approve of the ending and regard the naysayers as foolish in complaining about a series which throughout its run tried to be different, challenging and better than the half-baked fare which is usually offered as television drama. For those who know the ending (or aren’t so concerned about it), series creator David Chase discussed his intentions and the audience reaction with the New Jersey Star-Ledger.

Update: A David Chase comment from 2001 turned up via the NYT. I’m sure these are sentiments Cormac McCarthy would also agree with.

What’s the difference between what’s art and what isn’t art? That’s the hard question to answer. The only thing that I guess I believe is that a lot of what I see on the air and in other places is giving answers, and I don’t think art should give answers. I think art should only pose questions. And art should not fill in blanks for people, or I think that’s what’s called propaganda. I think art should only raise questions, a lot of which may be even dissonant and you don’t even know you’re being asked a question, but that it creates some kind of tension inside you.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• In praise of Cormac

• Cormac McCarthy book covers