The Stone Tape has accrued a considerable cult reputation since it was first broadcast as a BBC ghost story during Christmas, 1972. I was too young to see the original transmission—I used to hear awed reports from those who remembered it—and didn’t get to see it until the BFI brought out on DVD a few years ago. That disc is now deleted, and the play is another unfortunate omission from the BFI’s Ghost Stories box set, so this seems a good opportunity to point the curious to the full-length copy that’s currently on YouTube.

In the past I’ve compared Nigel Kneale, the writer of The Stone Tape, to HP Lovecraft. This isn’t a comparison the often curmudgeonly Kneale might have agreed with but you can find similarities in the way both Kneale and Lovecraft (in his later fiction) created scenarios featuring scientists or technical people which grade from science fiction to outright horror. The horror can be something ancient and earthbound or, as in the case of Kneale’s Quatermass cycle, it can be extraterrestrial. Kneale’s narratives may return continually to scientific investigation but he was smart enough to avoid explaining away his mysteries. The Stone Tape is an uncanny masterpiece that often seems so bare-bones you can hardly believe the effect it’s creating compared to lavishly-budgeted yet inferior feature films. Something about Kneale’s drama works it way insidiously under the skin then lodges there. It leaves with its mysteries intact.

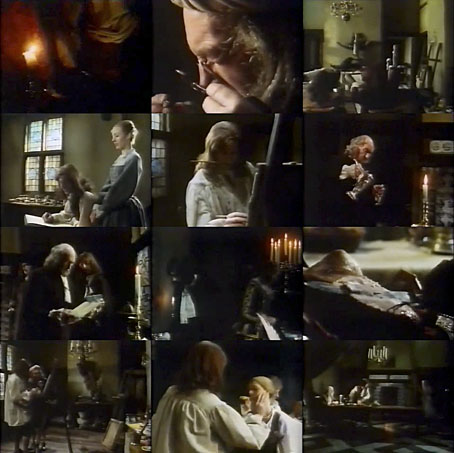

One reason Kneale’s Christmas play may have been left out of the BFI box is that it doesn’t fit the MR James model of accumulation-of-clues leading to revelation-of-spook. In Kneale’s story an industrial research and development team move into an old mansion building which turns out to be haunted. The manifestation of the ghost—usually the end point of most supernatural stories—quickly becomes an almost commonplace occurrence when the team decide to start probing its presence with their machines. Like most TV plays of the period this is done in the electronic studio but any absence of film atmosphere is compensated for by excellent writing and performances. Jane Asher plays a computer programmer and the only female professional in a group of loud and blustering men. She’s not only the person most sensitive to the spectral happenings but also proves to be the only one with the brains and tenacity to fathom the true nature of the haunting.

The conviction in the performances, Asher’s especially, and the quality and detail of Kneale’s characterisation, is what makes this production work so well. Among the other actors Michael Bryant is the stubborn team leader while Iain Cuthbertson plays the mediating foreman. Cuthbertson later had a major role in the cult TV serial Children of the Stones, and in 1979 was a memorable Karswell in an adaptation of MR James’ Casting the Runes. Also among the cast is Michael Bates who most people will know as the bellowing prison guard in A Clockwork Orange. The sound effects are by the Radiophonic Workshop’s Desmond Briscoe who also created electronic effects for The Haunting, Phase IV and The Man Who Fell to Earth. Director Peter Sasdy worked on a couple of the lesser Dracula films for Hammer but this is his finest hour-and-a-half. And if that isn’t enough priming for you I don’t know what else would suffice. I urge anyone who hasn’t seen this drama to turn off the lights and start the tape. It’s perfect Halloween viewing that grips to the very end.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Haunted: The Ferryman

• Schalcken the Painter