The conceit of a “soundtrack for an imaginary film” dates back at least as far as Gandharva by Beaver & Krause, although only the second half of that album was the imaginary soundtrack, and a rather vague one at that. (A variation on the Gandharva suite did become genuine soundtrack music, however, when Robert Fuest asked Gerry Mulligan to rework his sax improvisation for The Final Programme in 1973.) The imaginary soundtrack idea didn’t really catch on until the late 80s and early 90s, with serious efforts such as Barry Adamson’s excellent Moss Side Story emerging alongside an increasing and often lazy use of the term “imaginary soundtrack” as a descriptor employed by journalists writing about instrumental electronic albums.

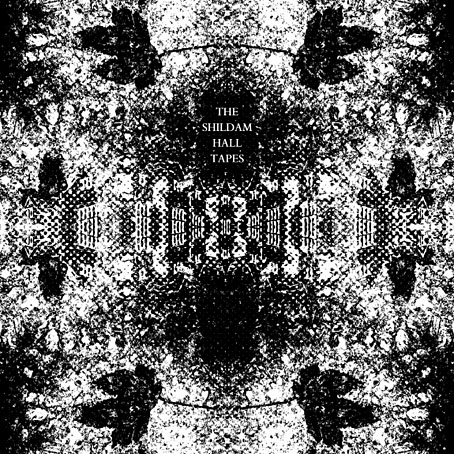

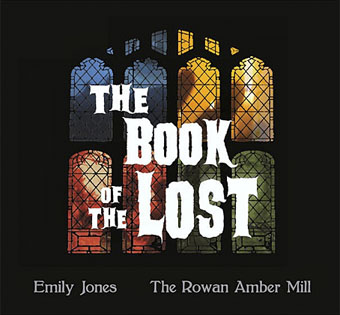

The Shildam Hall Tapes is neither lazy nor mis-labelled being the latest in this year’s themed compilation albums from A Year In The Country, and a collection described as “reflections on an imaginary film.”

In the late 1960s a film crew began work on a well-funded feature film in a country mansion, having been granted permission by the young heir of the estate. Amidst rumours of aristocratic decadence, psychedelic use and even possibly dabbling in the occult, the film production collapsed, although it is said that a rough cut of it and the accompanying soundtrack were completed but they are thought to have been filed away and lost amongst storage vaults.

Few of the cast or crew have spoken about the events since and any reports from then seem to contradict one another and vary wildly in terms of what actually happened on the set. A large number of those involved, including a number of industry figures who at the time were considered to have bright futures, simply seemed to disappear or step aside from the film industry following the film’s collapse, their careers seemingly derailed or cast adrift by their experiences.

Little is known of the film’s plot but several unedited sections of the film and its soundtrack have surfaced, found amongst old film stock sold as a job lot at auction—although how they came to be there is unknown. The fragments of footage and audio that have appeared seem to show a film which was attempting to interweave and reflect the heady cultural mix of the times; of experiments and explorations in new ways of living, a burgeoning counter culture, a growing interest in and reinterpretation of folk culture and music, early electronic music experimentation, high fashion, psychedelia and the crossing over of the worlds of the aristocracy with pop/counter culture and elements of the underworld.

The Shildam Hall Tapes takes those fragments as its starting point and imagines what the completed soundtrack may have sounded like; creating a soundtrack for a film that never was.

Track list:

1) Gavino Morretti—Dawn of a New Generation

2) Sproatly Smith—Galloping Backwards

3) Field Lines Cartographer—The Computer

4) Vic Mars—Ext – Day – Overgrown Garden

5) Circle/Temple—Maze Sequence

6) A Year In The Country—Day 12, Scene 2, Take 3; Hoffman’s Fall

7) The Heartwood Institute—Shildam Hall Seance

8) David Colohan—How We’ll Go Out

9) Listening Center—Cultivation I

10) Pulselovers—The Green Leaves of Shildam Hall

I’ve always enjoyed this kind of thing when it’s done well, as in Barry Adamson’s case, so was already predisposed to the new collection even before hearing it. The cumulative effect is much better than anticipated, thanks in part to a few deviations from earlier A Year In The Country compilations. The opening piece is by Gavino Morretti, a newcomer to the AYITC stable, and a musician whose albums to date are all in the imaginary soundtrack sub-genre. Morretti provides a marvellous piece in the Goblin/Fabio Frizzi manner that effortlessly conjures a title sequence of mists, coloured filters and Art Nouveau typefaces.

The following contributions range from the spookily atmospheric (Sproatly Smith, A Year In The Country, The Heartwood Institute) to electronic numbers such as The Computer by Field Lines Cartographer which suggests some kind of paranormal investigation like those in The Stone Tape and The Legend of Hell House. The biggest surprise for me was David Colohan’s How We’ll Go Out which is another electronic work, and very different to his earlier folk-oriented compositions. If, like me, you’ve been missing the “ghost” quotient among the recent releases on the Ghost Box label, then The Shildam Hall Tapes is a very welcome substitute: sinister, perfectly-pitched and leaving enough gaps in the scenario for the imagination to operate. I’m no doubt biased towards the format but for me this is the best A Year In The Country compilation to date so I’m now wondering what the follow-up will be like.

The Shildam Hall Tapes will be available for pre-order at Bandcamp from 10th July, and released on the 31st.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Audio Albion

• A Year In The Country: the book

• All The Merry Year Round

• The Quietened Cosmologists

• Undercurrents

• From The Furthest Signals

• The Restless Field

• The Marks Upon The Land

• The Forest / The Wald

• The Quietened Bunker

• Fractures