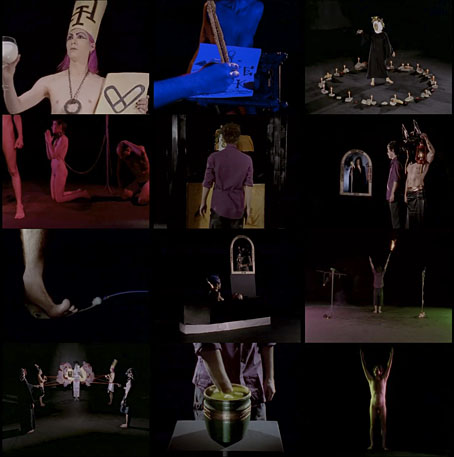

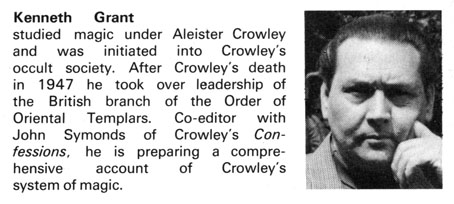

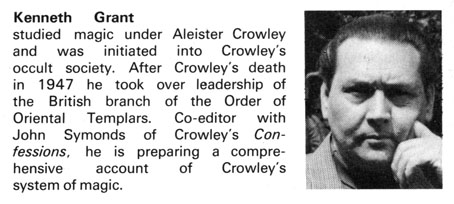

Going through some of my loose copies of Man, Myth and Magic recently turned up this article by Kenneth Grant that I’d forgotten about. I have two separate sets of Man, Myth and Magic: a complete edition in binders, and a partial collection of loose copies of the weekly “illustrated encyclopedia of the supernatural”. The partial collection is worth keeping for the unique articles that ran across the last two pages of every issue, all of which are absent (along with the magazine covers) from the bound edition. These articles formed the Frontiers of Belief series, a collection of essays of the kind one might find in magazines today such as Fate or Fortean Times. An earlier essay about Wilfried Sätty, Artist of the Occult, was reproduced here a few years ago; none of these pieces have ever been reprinted so it seems worthwhile putting another of the more interesting pieces online.

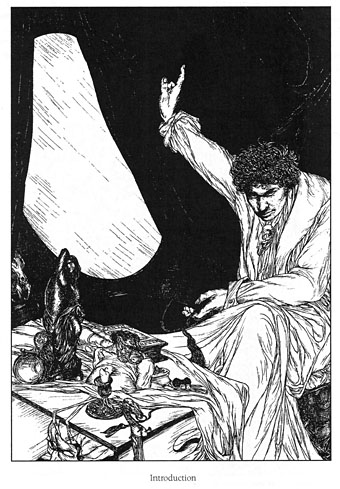

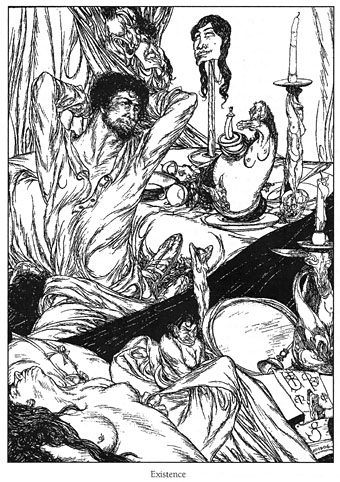

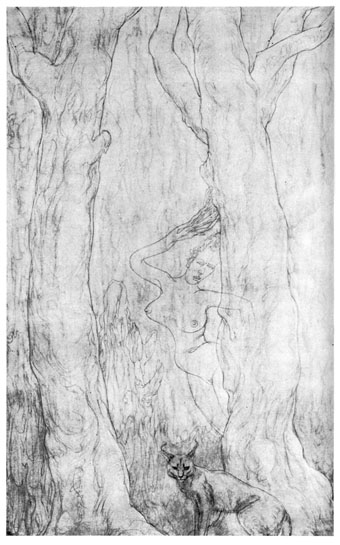

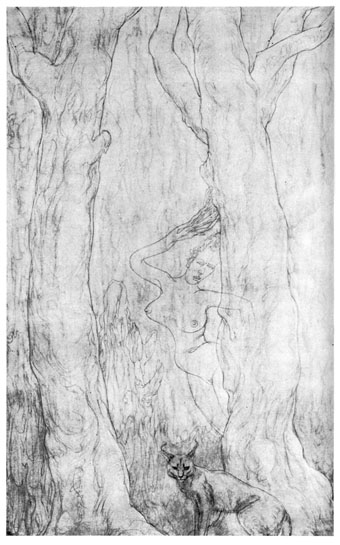

Kenneth Grant was the only active occultist among Man, Myth and Magic‘s roster of very serious and well-regarded writers and experts. Grant wrote several of the encyclopedia entries although not the one about Aleister Crowley, as you might expect, that entry going to Crowley’s executor and biographer, John Symonds. Grant was also a lifelong champion of HP Lovecraft’s fiction which explains this article; many of Grant’s later occult texts have a distinctly Lovecraftian flavour, and they often refer to Lovecraft and Arthur Machen as being the unconscious recipients of actual occult emanations or presences. Grant’s belief that the authors channelled these emanations into their fiction is central to this piece, a belief that Lovecraft would have dismissed even though several of his stories (not least The Call of Cthulhu) concern exactly this process. Grant connects Lovecraft with another artist whose work he championed throughout his life, Austin Osman Spare. It was Grant’s involvement with Man, Myth and Magic that put one of Spare’s drawings on the cover of the first issue, and further drawings inside the magazine, introducing the artist’s work to a new, highly receptive audience. The drawing below (Were-Lynx) appears in the magazine behind Grant’s text so I’ve scanned a text-free copy from Grant’s Cults of the Shadow (1975).

•

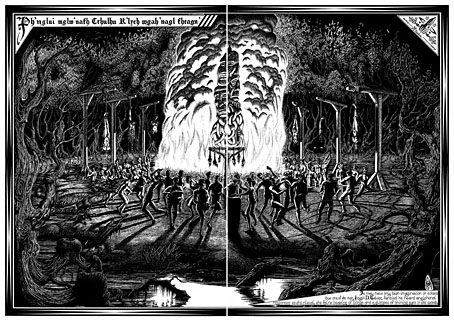

DREAMING OUT OF SPACE by Kenneth Grant

Malevolent powers are lurking in wait to project themselves into the sleeping minds of men: this terrifying idea is a recurring theme in the stories of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, who claimed that they came to him in nightmares. But were they simply bad dreams, or was he in fact receiving communications from an unknown source, as Kenneth Grant here suggests?

“I have watched for dryads and satyrs in the woods and fields at dusk”; illustration by Austin Osman Spare, who sensed the forces looming behind Lovecraft’s work, and was inspired to illustrate these presences.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft died in 1937; but the myth-cycle which he initiated in unrivalled tales of cosmic horror now raises the question whether it was a mere fiction engendered in the haunted mind of an obscure New England writer, or whether it foreshadowed a particularly sinister kind of occult invasion.

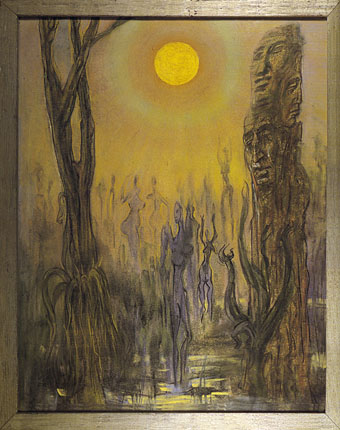

According to a well-known occult tradition, when Atlantis was submerged, not all perished. Some took refuge on other worlds, in other dimensions; others “slept” a willed and unnatural sleep through untold aeons of time. These awakened; they lurk now in unknown gulfs of space, the physical mechanism of human consciousness being unable to pick up their infinitely subtle vibrations. They lurk, waiting to return and rule the whole earth, as was their aim before the catastrophe that destroyed their corrupt civilization.

This tradition was a major theme in Lovecraft’s work. Until quite recently people read his stories and shuddered (if sufficiently honest and sensitive enough to admit their uncanny impact), not suspecting for a moment that such things could be.

Few know that Lovecraft dreamed most of his tales. And he sometimes thought that these dreams, or rather, nightmares, were caused by misdeeds in remotely distant incarnations when, perhaps, he had aimed at acquiring magical powers. These dreams were memories of the past and prophecies of the future, for he said that “nightmares are the punishment meted out to the soul for sins committed in previous incarnations—perhaps millions of years ago!”

In his life as Howard Phillips Lovecraft he tried again and again to bring himself to face squarely the ordeal through which he knew he would have to pass, if he were finally to resolve his spiritual difficulties. The issue is brought to the surface perhaps more clearly and urgently in his poems than in his stories. He is on the brink of making the critical discovery, of surprising the secret of his inner life, and he is forced back repeatedly by the dread, the stark soul-searing fear which he bottles up in his work and which he communicates so successfully—in neat doses—to his readers.

One of Lovecraft’s most vivid creations is the ancient book of hideous spells composed to facilitate traffic with creatures of unseen worlds. He ascribed its authorship to Abdul Alhazred, a mad Arab who flourished in Damascus about 700 AD. This grimoire, during the course of its mysterious career, is supposed to have been translated by the Elizabethan scholar Dr John Dee, into Greek, under the title of Necronomicon. It contains the Keys or Calls that unseal forbidden spaces of cosmic sleep, inhabited by elder forces that once infested the earth. The Keys are in a wild, unearthly tongue reminiscent of the Calls of Chanokh, or Enoch, which Dr Dee actually obtained through contact with non-terrestrial entities during his work with the magician, Sir Edward Kelley, whom Aleister Crowley claimed to have been in a previous life. It is possible that the “evil and abhorred Necronomicon” was suggested by the clavicles or Keys of Enoch, which Dee and Kelley discovered, and which Crowley later used to gain access to unknown dimensions.

Continue reading “Dreaming Out of Space: Kenneth Grant on HP Lovecraft”