Continuing an occasional series about artworks in feature films. I’ve been spending the past couple of weeks working my way through the Ken Russell filmography, rewatching familiar documentaries and feature films while acquainting myself with the portions of the Russell oeuvre that I’d missed in the past. Crimes of Passion (1984) was a film that I did see when it turned up on video in the late 1980s but I didn’t remember much about it apart from its overheated erotic atmosphere and a red/blue lighting scheme. It’s not one of Russell’s best—the script lurches uncomfortably between mundane domestic drama and lurid, sex-crazed delirium; Rick Wakeman’s synthesizer score is persistently annoying—but it does feature spirited performances by the lead actors, Kathleen Turner and Anthony Perkins.

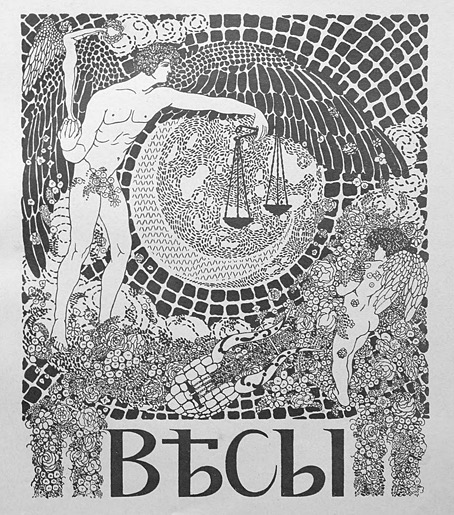

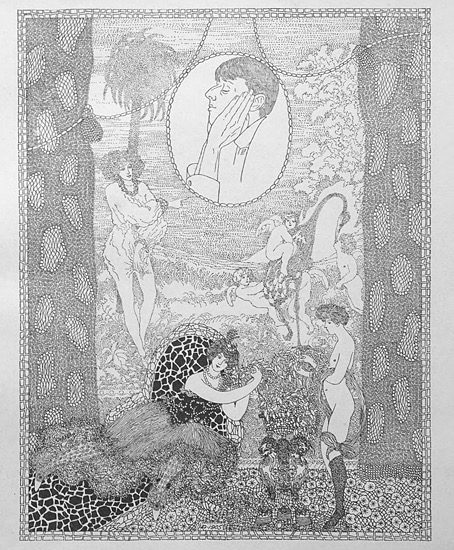

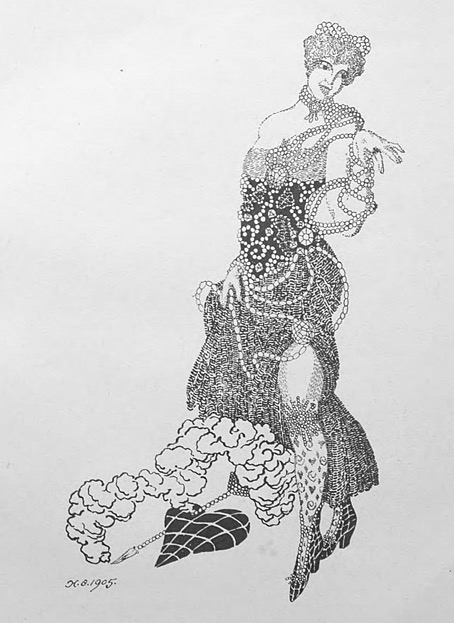

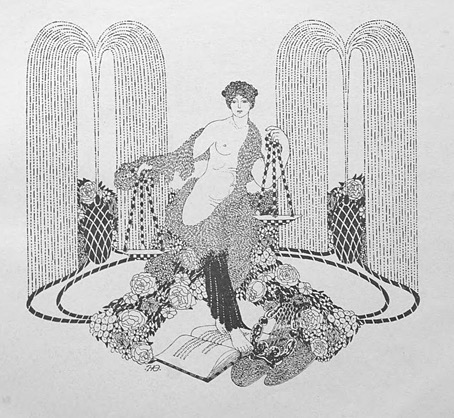

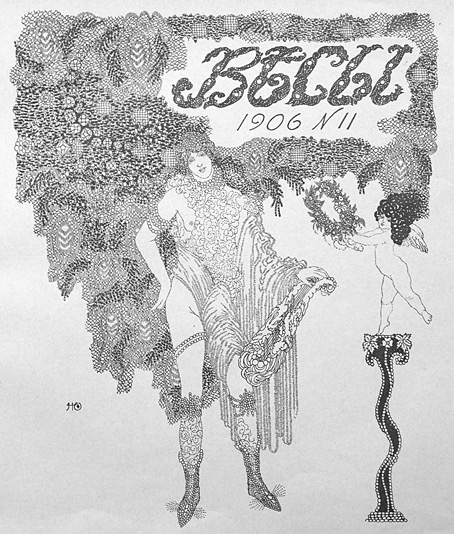

Turner is Joanna Crane, a swimwear designer who deals with the vacuity of her life by moonlighting as an in-demand prostitute named China Blue. (The polite term “sex worker” didn’t exist in the 1980s.) Russell delivers the art references early on, with unexpected cuts to erotic figures from Aubrey Beardsley’s Lysistrata (above), various Japanese shunga prints, and a flash of The Rape by René Magritte. Since the real woman behind the China Blue persona isn’t revealed until later in the film we don’t know at first that Joanna Crane’s apartment contains reproductions of some of the same pictures. She eventually admits to thinking of them during stressful moments.

Despite this admission, there’s nothing in the script of Crimes of Passion that warrants the references, Crane’s apartment could easily have been furnished in a blandly expensive manner suited to a successful designer. The only other character who seems remotely interested in art is Anthony Perkins’ Reverend Shayne, a splenetic, sex-obsessed preacher who has a hotel room next door to China Blue. In one of several references to Psycho, Shayne watches his neighbour’s erotic encounters through a spyhole. The walls of his own room are covered in a collage of religious and pornographic imagery but little is made of this.

The Lovers by René Magritte.

Joanna Crane and Bobby Grady (John Laughlin) in Joanna’s apartment. Among the pictures on the walls are Romeo and Juliet by Marc Chagall, The Embrace by Gustav Klimt, and The Kiss by Gustav Klimt.