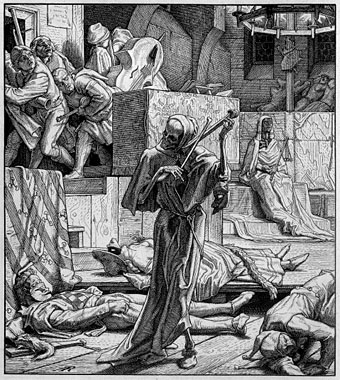

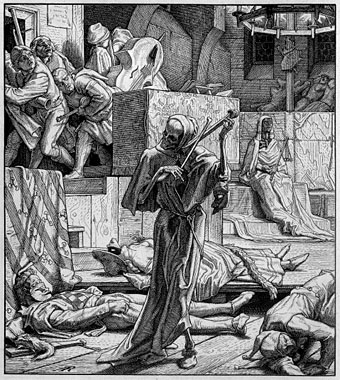

Der Tod als Erwürger (1851) by Alfred Rethel.

It’s a fact (sad or otherwise) that a substantial percentage of my music collection would make good Halloween listening but in that percentage a number of works are prominent as spooky favourites. So here’s another list to add to those already clogging the world’s servers, in no particular order:

Theme from Halloween (1978) by John Carpenter & Alan Howarth.

What a surprise… All John Carpenter‘s early films have electronic scores and great themes, Halloween being the most memorable, and one that’s gradually infected the wider musical culture as various hip hop borrowings and Heat Miser by Massive Attack demonstrate.

Monster Mash (1962) by Bobby “Boris” Pickett.

The ultimate Halloween novelty record. A host of imitators followed the success of this single while poor Bobby struggled to be more than a one-hit wonder. It wasn’t to be, this was his finest hour. Available on These Ghoulish Things: Horror Hits for Halloween with some radio spots by Bobby and a selection of other horror-themed rock’n’roll songs.

The Divine Punishment (1986) & Saint of the Pit (1988) by Diamanda Galás.

Parts 1 & 2 of Galás’s Masque of the Red Death, a “plague mass” trilogy based on the AIDS epidemic. These remain my favourite records by Ms Galás; on the first she reads/sings passages from the Old Testament accompanied by sinister keyboards, making the Bible sound as steeped in evil and metaphysical dread as the Necronomicon. On Saint of the Pit she turns her attention to French poets of the 19th century (Baudelaire, Gérard de Nerval & Tristan Corbière) while unleashing the full power of her operatic vocalizations. Einstürzende Neubauten’s FM Einheit adds some thundering drums. “Correct playback possible at maximum volume only.” Amen to that.

The Visitation (1969) by White Noise.

An electronic collage piece about a ghostly lover returning to his grieving girlfriend. White Noise were David Vorhaus working alongside BBC Radiophonic Workshop pioneers Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson to create an early work of British electronica and dark psychedelia. The Visitation makes full use of Derbyshire and Hodgson’s inventive tape effects and probably accounts for them being asked to score The Legend of Hell House a few years later. Immediately following this is the drums and screams piece, Electric Storm In Hell; play this loud and watch the blood drain from the faces of your Halloween guests.

Zeit (1972) by Tangerine Dream.

Subtitled “A largo in four movements”, Zeit is Tangerine Dream’s most subtle and restrained album, four long tracks of droning atmospherics.

The Masque of the Red Death (1997) read by Gabriel Byrne.

From Closed On Account Of Rabies, a Poe-themed anthology arranged by Hal Willner. The readings are of variable quality; Christopher Walken’s The Raven is effective (although I prefer Willem Defoe’s amended version on Lou Reed’s The Raven) while Dr John reads Berenice like one of Poe’s somnambulists. Gabriel Byrne shows how these things should be done.

De Natura Sonoris no. 2 (1971) by Krzysztof Penderecki.

More familiar to people as “music from The Shining“, this piece, along with much of the Polish composer‘s early work, really does sound like music in search of a horror film. His cheerily-titled Threnody For The Victims Of Hiroshima is one piece that won’t be used to sell cars any time soon. Kubrick also used Penderecki’s equally chilling The Dream of Jacob for The Shining score, together with pieces by Ligeti and Bartók.

Treetop Drive (1994) by Deathprod.

Helge Sten is a Norwegian electronic experimentalist whose solo work is released under the Deathprod name. “Electronic” these days often means using laptops and the latest keyboard and sampling equipment. Deathprod music is created on old equipment which renders its provenance opaque leaving the listener to concentrate on the sounds rather than be troubled by how they might have been created. The noises on the deceptively-titled Treetop Drive are a disturbing series of slow loops with squalling chords, anguished shrieks and some massive foghorn rumble that seems to emanate from the depths of Davy Jones’ Locker. Play it in the dark and feel the world ending.

Ouroborindra (2005) by Eric Zann.

Another collection of sinister electronica from the Ghost Box label (see this earlier post), referencing HP Lovecraft and Arthur Machen’s masterpiece, The White People. Spectral presences haunting the margins of the radio spectrum.

Theme from The Addams Family (1964) by Vic Mizzy.

Never the Munsters, always the Addams Family! If you don’t know the difference, you must be dead.

Happy Halloween!

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The music of the Wicker Man